Immunity: fighting against others and… your own

The immune system is a system of reactions designed to protect the body from the invasion of bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa and other harmful agents — the so—called pathogens. If we imagine that our body is a country, then the immune system can be compared to its armed forces. The more coordinated and adequate their response to pathogen intervention is, the more reliable the body’s defense will be.

There are a great many pathogens in the world, and in order to effectively combat all of them, as a result of long evolution, an intricate system of immune cells has formed, each of which has its own strategy for fighting. The cells of the immune system complement each other: they use different ways to destroy the pathogen, can enhance or weaken the effect of other cells, and also attract more and more fighters to the battlefield if they themselves cannot cope.

By attacking the body, pathogens leave molecular “clues” that are “picked up” by immune cells. Such evidence is called antigens.

Antigens are any substances that the body perceives as foreign and, accordingly, responds to their appearance by activating immunity. The most important antigens for the immune system are pieces of molecules located on the outer surface of the pathogen. Using these pieces, you can determine which aggressor attacked the body and ensure the fight against it.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Cytokines are the Morse code of the body

In order for immune cells to coordinate their actions in the fight against the enemy, they need a system of signals telling whom and when to engage in battle, or end the battle, or, conversely, resume it, and much, much more. For these purposes, cells produce small protein molecules called cytokines, for example, various interleukins (IL—1, 2, 3, etc.) [1]. It is difficult to assign an unambiguous function to many cytokines, but with some degree of conditionality they can be divided into five groups: chemokines, growth factors, pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory cytokines.

- Chemokines give the cell a signal that tells it where to move. This may be an infected place where all the combat units of our army need to be pulled together, or a certain organ of the immune system, where the cell will continue to undergo military literacy training.

- Growth factors help the cell determine which “military specialty” to choose for itself. By the names of these molecules, it is usually easy to understand which cells they are responsible for developing. For example, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF, GM-CSF) promotes the appearance of granulocytes and macrophages, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), as the name suggests, is responsible for the formation of new vessels of the circulatory system.

- Pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and immunoregulatory cytokines are said to “modulate” the immune response. It is these molecules that cells use to “talk” with each other, because any joint business must be strictly regulated so that key players do not get confused about what to do and do not interfere with each other, but effectively perform their functions. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, as the name suggests, contribute to the maintenance of inflammation, which is necessary for an effective immune response to fight pathogens, while anti-inflammatory cytokines help the body stop the war and bring the battlefield to a peaceful state. The signals of immunoregulatory cytokines can be decoded by cells in different ways, depending on what kind of cells they are and what other signals they will receive by that time.

The above—mentioned classification convention means that a cytokine belonging to one of the listed groups can play a diametrically opposite role in the body under certain conditions – for example, it can turn from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory.

Without a well-established connection between the types of troops, any sophisticated military operation is doomed to failure, so it is very important for the cells of the immune system to receive and give orders in the form of cytokines, interpret them correctly and act in a coordinated manner. If cytokine signals begin to be produced in very large quantities, then panic sets in in the cell ranks, which can lead to damage to one’s own body. This is called a cytokine storm: in response to incoming cytokine signals, the cells of the immune system begin to produce more and more of their own cytokines, which, in turn, act on the cells and enhance the secretion of themselves. A vicious circle is formed, which leads to the destruction of surrounding cells, and later neighboring tissues.

Pay off in order! Immune cells

Just as there are different types of troops in the armed forces, the cells of the immune system can be divided into two large branches — the innate and acquired immunity, for the study of which the Nobel Prize was awarded in 2011. [3], [4], [5]. Innate immunity is that part of the immune system that is ready to defend the body immediately as soon as a pathogen is attacked. The acquired (or adaptive) immune response takes longer to unfold upon first contact with the enemy, as it requires sophisticated preparation, but then it can carry out a more complex defense scenario of the body. Innate immunity is very effective in combating isolated saboteurs: it neutralizes them without disturbing specialized elite military units — adaptive immunity. If the threat turns out to be more significant and there is a risk of the pathogen penetrating deeper into the body, the cells of the innate immune system immediately signal this, and the cells of the acquired immune system enter the fray.

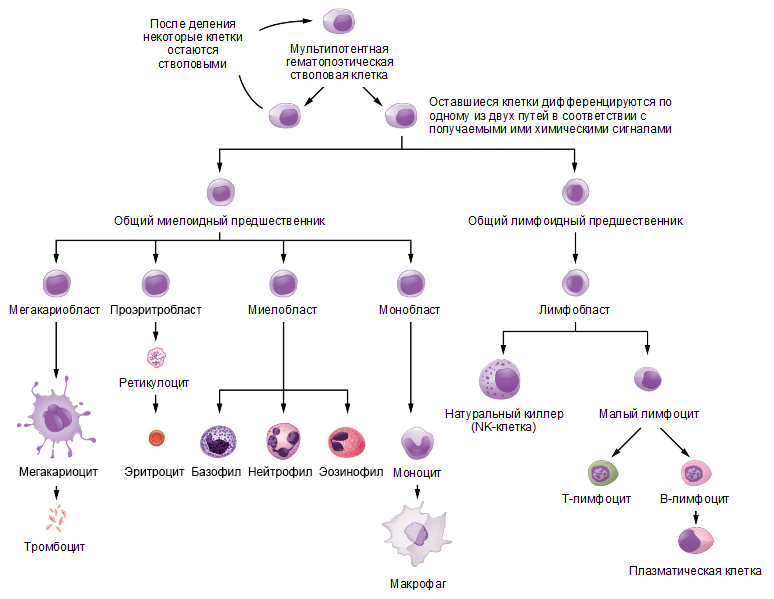

All immune cells of the body are formed in the bone marrow from a hematopoietic stem cell, which gives rise to two cells — common myeloid and common lymphoid progenitors. [2], [6]. Cells of acquired immunity originate from a common lymphoid precursor and, accordingly, are called lymphocytes, whereas cells of innate immunity can originate from both precursors. The scheme of differentiation of cells of the immune system is shown in Picture 1.

Picture 1. The scheme of differentiation of cells of the immune system. The hematopoietic stem cell gives rise to progenitor cells of the myeloid and lymphoid lines of differentiation, from which all types of blood cells are further formed. Source: website opentextbc.ca , the drawing is adapted.

Innate immunity — the regular Army

Innate immune cells recognize a pathogen by its specific molecular markers, the so—called pathogenicity patterns. [7]. These markers do not allow us to accurately determine whether a pathogen belongs to a particular species, but only signal that the immune system has encountered outsiders. Fragments of the bacterial cell wall and flagella, double-stranded RNA and single-stranded DNA of viruses, etc. can serve as such markers for our body. With the help of special innate immunity receptors, таких как TLR (Toll-like receptors, Толл-подобные рецепторы) and NLRs (Nod-like receptors, Nod-like receptors), cells interact with pathogenicity patterns and begin to implement their protective strategy.

Now let’s take a closer look at some cells of the innate immune system.

Macrophages and dendritic cells absorb (phagocytize) the pathogen, and already inside themselves, using the contents of vacuoles, they dissolve it. This method of destroying the enemy is very convenient: the cell that carried it out can not only continue to function actively, but also gets the opportunity to preserve fragments of the pathogen — antigens, which, if necessary, will serve as an activation signal for cells of adaptive immunity. Dendritic cells are the best at this, as they act as messengers between the two branches of the immune system, which is necessary for the successful suppression of infection..

Neutrophils, the most numerous immune cells in human blood, travel through the body for most of their lives. When they encounter a pathogen, they absorb and digest it, but after a “hearty meal” they usually die. Neutrophils are kamikaze cells, and death is their main mechanism of action. At the moment of neutrophil death, the contents of the granules in them are released — substances with an antibiotic effect — and in addition, a network of the cell’s own DNA (NETs, neutrophil extracellular tracts) is scattered, into which nearby bacteria enter — now they become even more visible to macrophages.

Eosinophils, basophils and mast cells secrete the contents of their granules into the surrounding tissue — chemical protection against large pathogens, for example, parasitic worms. However, as is often the case, civilians can also be poisoned by chemicals, and these cells are widely known not so much for their direct physiological role as for their involvement in the development of an allergic reaction.

In addition to the aforementioned myeloid cells, lymphoid cells, which are called lymphoid cells of innate immunity, also work in innate immunity. They produce cytokines and, accordingly, regulate the behavior of other body cells.

One of the types of these cells is the so—called natural killers (or NK cells). They are the infantry in the body’s armed forces: they fight infected cells one—on-one, engaging in hand-to-hand combat with them.

NK cells secrete perforin granzyme B proteins.

The first, as the name implies, perforates the cell membrane of the target, embedding itself in it, and the second, like buckshot, penetrates through these gaps and triggers cell death, splitting the proteins that form it.

Surprisingly, at different stages of their development, some cells of the immune system can perform functions that are opposite to each other. Thus, a heterogeneous group of precursors of various innate immune cells is isolated, which in such an immature form suppress the immune response. That’s what they were called.: myeloid suppressor cells. Their number increases in the body in response to the appearance of a chronic infection or cancer. The role of such cells is very important, because they do not allow other soldiers of the army of immunity to fight the enemy too hard, thereby damaging the civilian population — innocent cells located nearby.

Adaptive immunity — special forces of the body's armed forces

Adaptive immunity cells — T– and B-lymphocytes can be compared to special forces units. The fact is that they are able to recognize many individual antigens of pathogens due to specialized receptors on their surface. These receptors are called T-cell (TCR, T-cell receptor) and B-cell (BCR, B-cell receptor), respectively. Due to the intricate process of TCR and BCR formation, each B or T lymphocyte carries its own unique receptor for a specific, unique antigen.

In order to understand how the T-cell receptor works, we first need to discuss another important family of proteins, the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). [9]. These proteins are the molecular “passwords” of the body, allowing the cells of the immune system to distinguish their compatriots from the enemy. In any cell, there is a constant process of protein degradation. A special molecular machine, the immunoproteasome— breaks down proteins into short peptides that can be embedded in the MHC and presented to the T-lymphocyte like an apple on a plate. With the help of TCR, he “sees” the peptide and recognizes whether it belongs to the body’s own proteins or is foreign. At the same time, the TCR checks whether it is familiar with the MHC molecule, which allows it to distinguish its own cells from “neighboring” cells, that is, cells of the same species, but of a different individual. It is the coincidence of MHC molecules that is necessary for the engraftment of transplanted tissues and organs, hence such a complicated name.: histos means “cloth” in Greek. In humans, MHC molecules are also called HLA (human leukocyte antigen — human leukocyte antigen).

T-lymphocytes

To activate a T-lymphocyte, it needs to receive three signals. The first of these is the interaction of TCR with MHC, that is, antigen recognition. The second is the so—called costimulatory signal transmitted by the antigen-presenting cell through CD80/86 molecules to CD28 located on the lymphocyte. The third signal is the production of a cocktail of many pro-inflammatory cytokines. If any of these signals breaks down, it can have serious consequences for the body, such as an autoimmunity reaction.

There are two types of molecules of the main histocompatibility complex: MHC-I and MHC-II. The first one is present on all cells of the body and carries peptides of cellular proteins or proteins of the virus that infected it. A special subtype of T cells — T-killers (they are also called CD8+ T-lymphocytes) — it interacts with the MHC-I—peptide complex with its receptor. If this interaction is strong enough, it means that the peptide that the T cell sees is not characteristic of the body and, accordingly, may belong to an enemy virus that has invaded the cell. It is urgently necessary to neutralize the trespasser, and the T-killer copes with this task perfectly. It, like an NK cell, secretes the proteins perforin and granzyme, which leads to lysis of the target cell.

T-cell receptor of another subtype of T-lymphocytes — T helper cells (Th cells, CD4+ T lymphocytes) — interacts with the complex “MHC-II—peptide”. This complex is not present on all cells of the body, but mainly on immune cells, and peptides that can be presented by the MHC-II molecule are fragments of pathogens captured from the extracellular space. If the T-cell receptor interacts with the MHC-II—peptide complex, then the T cell begins to produce chemokines and cytokines that help other cells effectively carry out their function of fighting the enemy. That’s why these lymphocytes are called helpers – from the English helper. Among them, there are many subtypes that differ in the range of cytokines produced and, consequently, their role in the immune process. For example, there are Th1 lymphocytes, which are effective in fighting intracellular bacteria and protozoa, Th2 lymphocytes, which help B cells in their work and are therefore important for resisting extracellular bacteria (which we will talk about soon), Th17 cells and many others.

Among CD4+ T cells, there is a special subtype of cells called regulatory T lymphocytes. They can be compared to the military prosecutor’s office, restraining the fanaticism of soldiers rushing into battle and preventing them from harming the civilian population. These cells produce cytokines that suppress the immune response, and thus weaken the immune response when the enemy is defeated.

The fact that the T-lymphocyte recognizes only foreign antigens, and not the molecules of its own body, is a consequence of an ingenious process called selection. It occurs in a specially created organ for this purpose, the thymus, where T cells complete their development. The essence of the selection is as follows: the cells surrounding a young or naive lymphocyte are shown (presented) he needs peptides of his own proteins. The lymphocyte that recognizes these protein fragments too well or too poorly is destroyed. The surviving cells (which is less than 1% of all T-lymphocyte precursors that have entered the thymus) have an intermediate affinity for the antigen, therefore, they usually do not consider their own cells targets for attack, but have the ability to react to a suitable foreign peptide. Selection in the thymus is a mechanism of the so—called central immunological tolerance.

There is also peripheral immunological tolerance. During the development of infection, the dendritic cell, like any cell of innate immunity, is affected by images of pathogenicity. Only after that, it can mature, begin to express additional molecules on its surface to activate the lymphocyte and effectively present antigens to T-lymphocytes. If a T-lymphocyte encounters an immature dendritic cell, it does not activate, but self-destructs or is suppressed. This inactive state of the T cell is called anergy. In this way, the pathogenic effect of autoreactive T-lymphocytes is prevented in the body, which for one reason or another survived during selection in the thymus.

All of the above applies to αß-T-lymphocytes, however, there is another type of T-cells — γδ-T-lymphocytes (the name determines the composition of the protein molecules that form TCR) [11]. They are relatively small in number and mainly inhabit the intestinal mucosa and other barrier tissues, playing an important role in regulating the composition of microbes living there. In γδ-T cells, the antigen recognition mechanism differs from αß-T-lymphocytic and does not depend on TCR [12].

B-lymphocytes

B lymphocytes carry a B-cell receptor on their surface [13]. Upon contact with the antigen, these cells are activated and transformed into a special cellular subtype — plasma cells with the unique ability to secrete their B-cell receptor into the environment — these are the molecules we call antibodies. Thus, both the BCR and the antibody have an affinity for the antigen they recognize, as if they “stick” to it. This allows antibodies to envelop (opsonize) cells and viral particles coated with antigen molecules, attracting macrophages and other immune cells to destroy the pathogen. Antibodies are also able to activate a special cascade of immunological reactions called the complement system, which leads to perforation of the pathogen’s cell membrane and its death.

For the effective meeting of adaptive immunity cells with dendritic cells carrying foreign antigens in the MHC and therefore working as “connected”, there are special immune organs in the body — lymph nodes. Their distribution throughout the body is heterogeneous and depends on how vulnerable a particular border is. Most of them are located near the digestive and respiratory tracts, because the penetration of the pathogen with food or inhaled air is the most likely method of infection.

The development of an adaptive immune response takes a long time (from a few days to two weeks), and in order for the body to protect itself from an already familiar infection faster, so-called memory cells are formed from T and B cells that participated in past battles. Like veterans, they are present in small numbers in the body, and if a pathogen familiar to them appears, they are reactivated, quickly divide and go out to defend the borders with an army.

The logic of the immune response

When the body is attacked by pathogens, the cells of the innate immune system — neutrophils, basophils and eosinophils – enter the battle first. They secrete the contents of their granules outside, which can damage the bacterial cell wall, as well as, for example, increase blood flow so that as many cells as possible rush to the infection site.

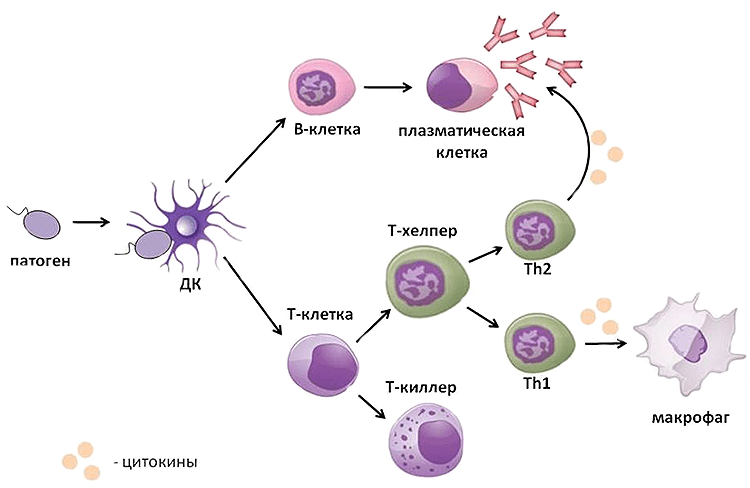

At the same time, the dendritic cell that has absorbed the pathogen rushes to the nearest lymph node, where it transmits information about it to the T and B lymphocytes located there. They activate and travel to the pathogen’s location (Fig. 2). The battle rages: T-killers, upon contact with an infected cell, kill it, T-helpers help macrophages and B-lymphocytes to implement their defense mechanisms. As a result, the pathogen dies, and the victorious cells are laid to rest. Most of them die, but some become memory cells that settle in the bone marrow and wait for the body to need their help again.

Picture 2. The scheme of the immune response. The pathogen that has entered the body is detected by a dendritic cell, which moves to the lymph node and transmits information about the enemy to T and B cells there. They are activated and exit into the tissues, where they realize their protective function: B lymphocytes produce antibodies, T-killers use perforin and granzyme B to kill the pathogen, and T-helpers produce cytokines that help other cells of the immune system in the fight against it. The scheme was compiled by the author of the article.

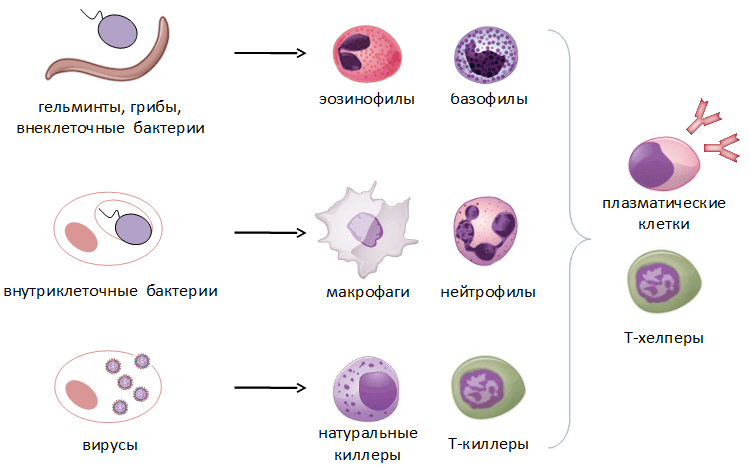

This is what the pattern of any immune response looks like, but it can vary markedly depending on which pathogen has entered the body. If we are dealing with extracellular bacteria, fungi, or, say, worms, then the main armed forces in this case will be eosinophils, B cells that produce antibodies, and Th2 lymphocytes that help them in this. If intracellular bacteria have settled in the body, then macrophages, which can absorb the infected cell, and Th1 lymphocytes, which help them in this, first of all rush to the rescue. Well, in the case of a viral infection, NK cells and T-killers enter the battle, which destroy infected cells by contact killing.

As we can see, the variety of types of immune cells and their mechanisms of action is no coincidence: for each type of pathogen, the body has its own effective way of fighting (Pic. 3).

Picture 3. The main types of pathogens and the cells involved in their destruction. The scheme was compiled by the author of the article.

The civil war is rumbling…

Unfortunately, no war is complete without civilian casualties. Long and intensive defense can be costly to the body if aggressive, highly specialized troops get out of control. Damage to the body’s own organs and tissues by the immune system is called an autoimmune process. [3]. About 5% of humanity suffers from diseases of this type.

The selection of T-lymphocytes in the thymus, as well as the removal of autoreactive cells in the periphery (central and peripheral immunological tolerance), which we discussed earlier, cannot completely rid the body of autoreactive T-lymphocytes. As for B-lymphocytes, the question of how strictly their selection is carried out is still open. Therefore, there are necessarily many autoreactive lymphocytes in each person’s body, which, in the event of an autoimmune reaction, can damage their own organs and tissues in accordance with their specificity.

Both T and B cells can be responsible for autoimmune lesions of the body. The former directly kill innocent cells carrying the corresponding antigen, and also help autoreactive B cells in the production of antibodies. T-cell autoimmunity has been well studied in rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and many other diseases.

B-lymphocytes are much more sophisticated. First, autoantibodies can cause cell death by activating the complement system on their surface or by attracting macrophages. Secondly, the receptors on the cell surface can become targets for antibodies. When such an antibody binds to a receptor, it can either be blocked or activated without a real hormonal signal. This happens in Graves’ disease: B lymphocytes produce antibodies against the TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) receptor, mimicking the effect of the hormone and, consequently, enhancing the production of thyroid hormones. [14]. In myasthenia gravis, antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor block its action, which leads to impaired neuromuscular conduction. Thirdly, autoantibodies, together with soluble antigens, can form immune complexes that settle in various organs and tissues (for example, in the renal glomeruli, joints, and vascular endothelium), disrupting their work and causing inflammatory processes.

As a rule, an autoimmune disease occurs suddenly, and it is impossible to determine exactly what caused it. It is believed that almost any stressful situation can serve as a trigger, whether it is an infection, injury, or hypothermia. A significant contribution to the likelihood of an autoimmune disease is made by both a person’s lifestyle and a genetic predisposition — the presence of a specific variant of a gene.

Predisposition to one or another autoimmune disease is often associated with certain alleles of the MHC genes, which we have already discussed a lot. Thus, the presence of the HLA-B27 allele can serve as a marker of predisposition to the development of ankylosing spondylitis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and other diseases.. Interestingly, the presence of the same HLA-B27 in the genome correlates with effective protection against viruses: for example, carriers of this allele have a reduced chance of contracting HIV or hepatitis C. [15], [16]. This is another reminder that the more aggressively the army fights, the more likely civilian casualties are.

In addition, the level of autoantigen expression in the thymus can influence the development of the disease. For example, the production of insulin and, consequently, the frequency of presentation of its antigens to T cells varies from person to person. The higher it is, the lower the risk of developing type 1 diabetes, as this allows the removal of insulin-specific T lymphocytes.

All autoimmune diseases can be divided into organ-specific and systemic. In organ-specific diseases, individual organs or tissues are affected. For example, in multiple sclerosis, the myelin sheath of neurons, in rheumatoid arthritis, joints, and in type I diabetes mellitus, the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Systemic autoimmune diseases are characterized by damage to many organs and tissues. Such diseases include, for example, systemic lupus erythematosus and primary Sjogren’s syndrome, affecting connective tissue. More details about these diseases will be described in other articles of the special project.

Conclusion

As we have already seen, immunity is a complex network of interactions at both the cellular and molecular levels. Even nature could not create an ideal system that reliably protects the body from pathogen attacks and at the same time does not damage its own organs under any circumstances. Autoimmune diseases are a side effect of the highly specific functioning of the adaptive immune system, the costs that we have to pay for the opportunity to successfully exist in a world teeming with bacteria, viruses and other pathogens.

Medicine, a human creation, cannot fully fix what was created by nature, so today none of the autoimmune diseases are completely cured. Therefore, the goals that modern medicine strives to achieve are timely diagnosis of the disease and effective relief of its symptoms, which directly affects the quality of life of patients. However, in order for this to be possible, it is necessary to raise public awareness about autoimmune diseases and ways to treat them. “Forewarned means armed!” is the motto of the public organizations created for this purpose all over the world.

Apollinaria Bogolyubova

Photo: pbs.twimg.com

Published

July, 2024

Duration of reading

About 5-6 minutes

Category

The immune system

Share