Key signs of aging

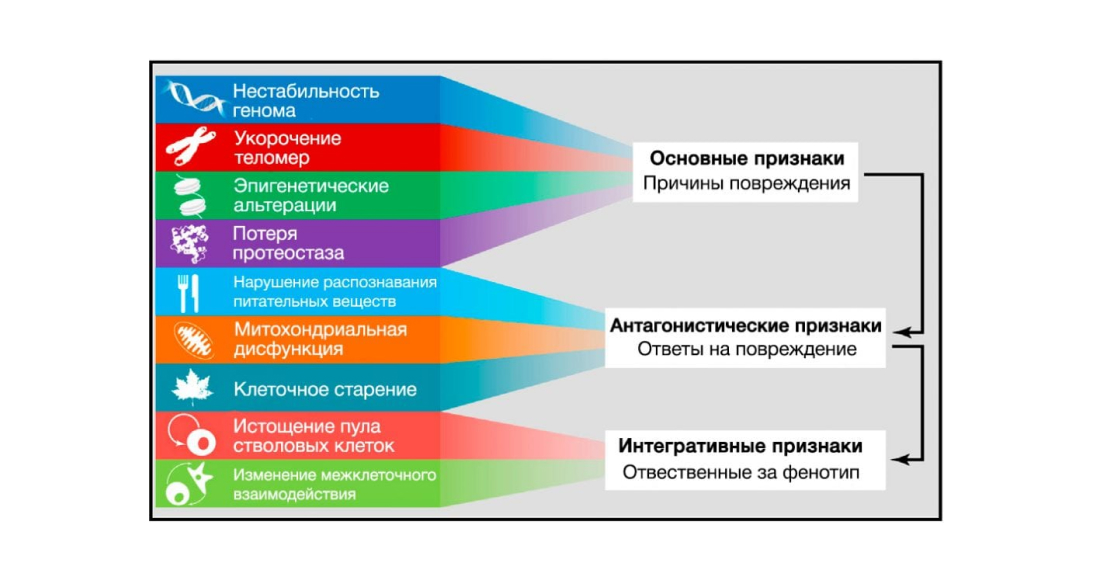

Ageing is characterised by the gradual loss of physiological integrity of the body, leading to impairment of its functions and an increased risk of death. This deterioration is a major risk factor for major human pathologies, including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. In the recent past, scientists have made unprecedented advances in the study of aging, especially with the establishment of the fact that the rate of aging is to some extent controlled by genetic and biochemical processes preserved during evolution. This review lists 9 potential key traits that are common to the aging process in various organisms, with a focus on mammals.

These features include: genome instability, telomere shortening, epigenetic alterations, impaired proteostasis, impaired nutrient recognition, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell pool depletion and altered intercellular communication. The main objective is to determine the relationship between potential key attributes and their relative contribution to aging with the ultimate goal of establishing pharmaceutical targets that will, with minimal side effects, improve human health with aging-induced changes.

Introduction

Aging, broadly defined as a time-dependent decline in function, affects most living organisms. Throughout human history, it has aroused curiosity and excited the imagination, although only 30 years have passed since the beginning of a new era in ageing research, marked by the production of the first long-lived Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) lines (Klass, 1983). Today, aging is the subject of rigorous scientific research based on the expanding knowledge of the molecular and cellular basis of life and disease. In the current context, many parallels can be drawn between ageing research and cancer research done in previous decades. A key moment in the field of cancer research was the publication of a landmark paper that listed the six most important hallmarks of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000), a list that has recently been expanded to ten (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). This systematisation has helped to make sense of the nature of cancer and the mechanisms underlying it.

At first glance, aging and cancer may seem like opposite processes: cancer is the consequence of the disruption of cellular adaptation mechanisms (including their over-activation), whereas aging is characterised by their loss. But if we dig deeper, we will see that aging and cancer have common roots. It is widely recognised that the accumulation of cellular damage over time is a major cause of ageing (Gems and Partridge, 2013; Kirkwood, 2005; Vijg and Campisi, 2008).

At the same time, cellular damage can lead to abnormal cellular advantages that can eventually become cancerous. Thus, cancer and aging can be considered as two different manifestations of the same process, the accumulation of cellular damage. In addition, some aging-associated pathologies, such as atherosclerosis and inflammation, involve uncontrolled cell division and hyperfunction (Blagosklonny, 2008). Based on this concept, several questions have arisen in the field of aging research concerning the physiological source of damage causing aging, compensatory responses aimed at restoring homeostasis, the relationship between different types of damage and compensatory responses, and the possibility of exogenous interventions aimed at slowing down aging.

In this paper, we have attempted to identify and classify the major cellular and molecular signatures of aging. We propose nine major signatures of aging that are thought to contribute to the process and define its phenotype (Figure 1). Given the complexity of the issue, we will focus on the current understanding of mammalian aging, taking into account cutting-edge research on simpler organisms (Gems and Partridge, 2013; Kenyon, 2010). Each key trait must fulfil the following criteria: (1) it must be observed during normal aging; (2) its experimental enhancement must result in accelerated aging; and (3) its experimental attenuation must slow the progression of normal aging and thereby increase healthy lifespan. All of the proposed traits fulfil these criteria to varying degrees, which will be discussed for each trait separately. The last criterion is the most elusive, even when reduced to a single aspect of aging. For this reason, interventions that have the potential to slow aging do not affect all key attributes. This contradiction is resolved by the excessive number of links between key attributes of aging, so that experimental improvement of one may affect the others.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Published

June, 2024

Duration of reading

About 10-15 minutes

Category

Aging and youth

Share

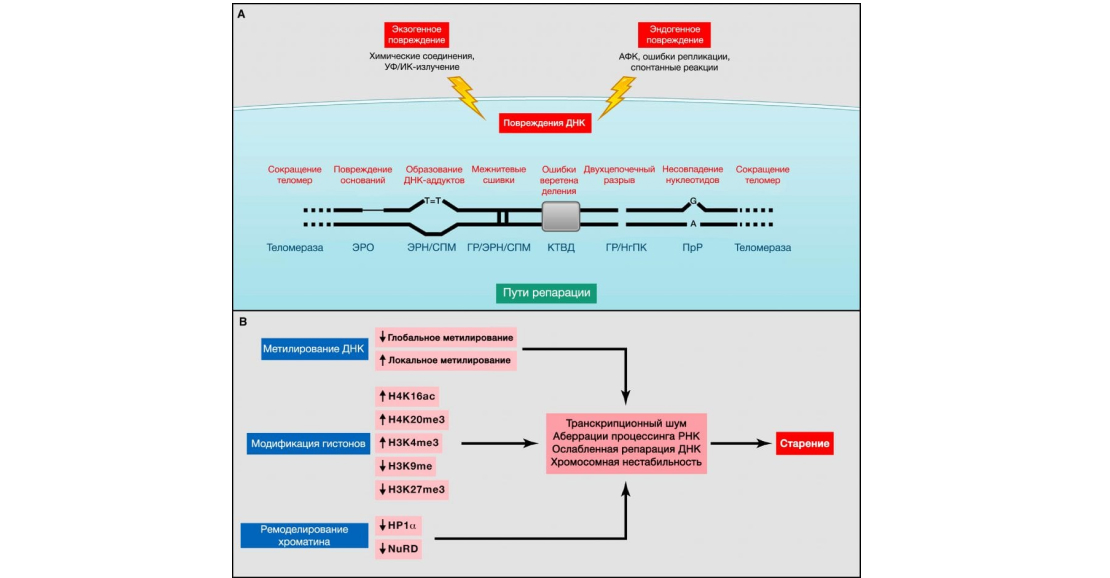

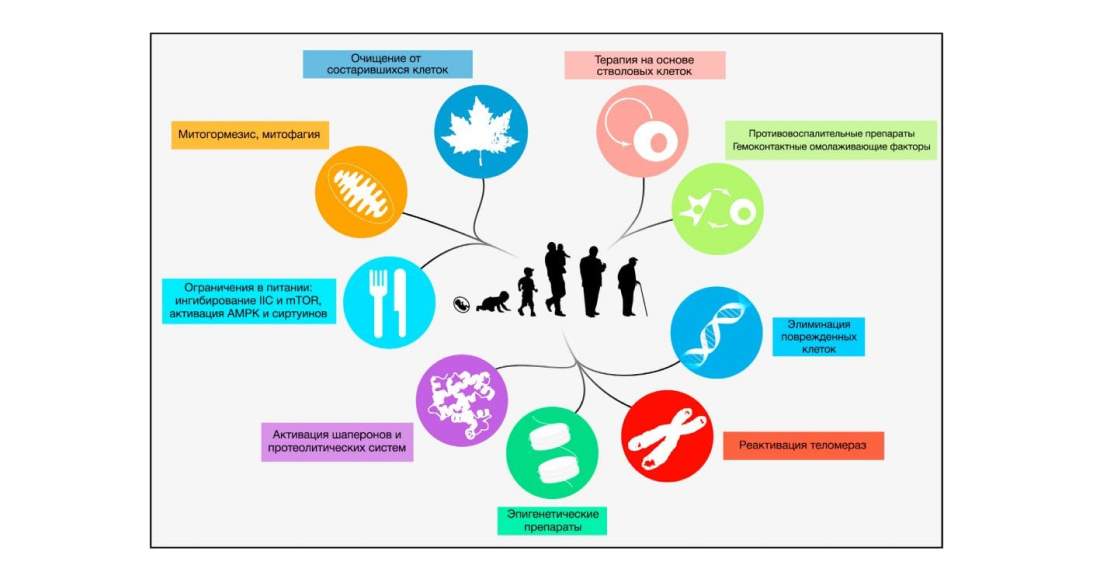

Figure 1: Key signs of ageing. Source: Cell Journal

The diagram depicts the nine hallmarks described in this review: genome instability, telomere shortening, epigenetic alterations, impaired proteostasis, impaired nutrient recognition, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell pool depletion, and altered intercellular communication.

Genome instability

One of the common links in the aging process is the accumulation of genetic damage throughout life (Moskalev et al., 2012) (Figure 2A). Moreover, many diseases of premature aging, notably Werner syndrome and Bloom syndrome, result from increased accumulation of DNA damage (Burtner and Kennedy, 2010), although the relevance of these and other progeroid syndromes to normal aging remains unclear, in part because they replicate only some features of aging. DNA integrity and stability is constantly threatened by both exogenous (physical, chemical and biological agents) and endogenous factors such as DNA replication errors, spontaneous hydrolysis reactions and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Hoeijmakers, 2009). Genetic disorders arising from internal and external damage are quite diverse and include point mutations, translocations, chromosome shortening and lengthening, telomere shortening and gene damage caused by integration of viruses or transposons. To minimise this damage, organisms have evolved a complex network of DNA repair mechanisms that together can cope with most damage to nuclear DNA (Lord and Ashworth, 2012). Systems for maintaining genome stability include specific mechanisms for stabilising the required length and functionality of telomeres (this is part of another key trait identified below) and for maintaining mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) integrity (Blackburn et al., 2006; Kazak et al., 2012). In addition to direct DNA damage, defects in nuclear architecture, known as laminopathies, can also lead to genome destabilisation and premature ageing (Worman, 2012).

Figure 2: Genomic and epigenetic alterations. Source: Journal of Cell

(A) Genomic instability and telomere shortening. Endogenous or exogenous agents can stimulate multiple DNA lesions, schematically represented on a single chromosome. Such damage can be repaired by a variety of mechanisms. Excessive DNA damage or insufficient DNA repair contributes to aging. Note that both nuclear and mitochondrial (not presented here) DNA undergo age-related genomic alterations. ERO, excisional base excision repair; GR, homologous recombination; ERN, excisional nucleotide excision repair; NgPC, nonhomologous end joining; PrR, postreplicative repair; AFC, reactive oxygen species; SPM, synthesis on damaged matrix; CTWD, division spindle checkpoint (Vijg, 2007).

(B) Epigenetic alterations. Changes in DNA methylation or acetylation and methylation of histones, as well as other chromatin-associated proteins, can cause epigenetic alterations that contribute to the aging process.

Nuclear DNA

Somatic mutations accumulate with age in human cells and model organisms (Moskalev et al., 2012). Other forms of DNA damage are also associated with aging: aneuploidies and variations in the number of gene copies (Faggioli et al., 2012; Forsberg et al., 2012). High clonal mosaicism of large chromosomal abnormalities has also been documented (Jacobs et al., 2012; Laurie et al., 2012). All of these forms of rearrangements in DNA can affect key genes and transcriptional pathways, resulting in failing cells that can jeopardise tissue and organismal homeostasis if not removed by apoptosis or acquire a senescent phenotype. This is particularly important with respect to how DNA damage affects the functionality of stem cells, preventing them from playing their role in tissue renewal (Jones and Rando, 2011; Rossi et al., 2008) (See ‘stem cell depletion’).

Evidence for a causal relationship between increased genomic damage over the life course and aging comes from studies in mice and humans that show that deficiencies in DNA repair mechanisms accelerate aging in mice and underlie human progeroid syndromes such as Werner syndrome, Bloom syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy, Cockayne syndrome, and Seckel syndrome (Gregg et al, 2012; Hoeijmakers, 2009; Murga et al., 2009). Moreover, transgenic mice overexpressing BubR1, a component of the mitotic cycle checkpoint that controls precise chromosome segregation, show high resistance to aneuploidy and tumour transformation, as well as increased healthy lifespan (Baker et al., 2013). The latter results serve as experimental evidence that artificial strengthening of nuclear DNA repair mechanisms can slow down aging.

Mitochondrial DNA

Age-related mtDNA mutations and deletions also contribute to aging (Park and Larsson, 2011). mtDNA is considered to be the main target of age-related somatic mutations that develop due to the action of the oxidative microenvironment of mitochondria, lack of protective mtDNA histones, and low efficiency of repair mechanisms compared to nuclear DNA (Linnane et al., 1989). The involvement of mtDNA mutations in the aging process has been questioned because of the large number of copies of the mitochondrial genome, which allow the coexistence of the mutant genome and the ‘wild-type’ genome in the same cell (this phenomenon is otherwise referred to as ‘heteroplasmy’). However, analyses of single cells have shown that, despite the low overall level of mtDNA mutations, the mutational burden of individual senescent cells becomes significant and can reach a state of homoplasmy in which the mutant genome predominates (Khrapko et al., 1999). Interestingly, contrary to current expectations, most mtDNA mutations in mature or senescent cells are caused by replication errors early in life rather than oxidative damage. These mutations can undergo polyclonal expansion and cause dysfunction of the respiratory chain in different tissues (Ameur et al., 2011). Studies of patients with accelerated ageing and HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral drugs that inhibit mtDNA replication support the concept of clonal expansion of early-life mtDNA mutations (Payne et al., 2011).

The first evidence that mtDNA damage plays an important role in human aging and the development of age-related diseases came from a study of multisystem human diseases caused by mtDNA mutations that are partly phenocopies of aging (Wallace, 2005). The following evidence was obtained in a study of mice with mitochondrial γ-DNA polymerase deficiency. These mutant mice show signs of accelerated aging and have a shorter lifespan in association with random point mutations and mtDNA deletions (Kujoth et al., 2005; Trifunovic et al., 2004; Vermulst et al., 2008). Mitochondrial function of cells from these mice is impaired, but the abnormalities are not accompanied by an increase in AFC production (Edgar et al., 2009; Hiona et al., 2010). Moreover, stem cells from these progeroid mice are particularly sensitive to the accumulation of mutations in mtDNA (Ahlqvist et al., 2012) (See Stem Cell Depletion). Further studies are needed to determine whether genetic manipulations that reduce the number of mtDNA mutations can increase longevity.

Nuclear architecture

Defects in the nuclear lamina can cause genome instability (Dechat et al., 2008). Nuclear proteins of intermediate filaments (lamins) constitute the main part of nuclear lamina and are involved in maintaining the conservation of genetic material, representing a framework for the attachment of chromatin and protein complexes that regulate genome stability (Gonzalez-Suarez et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2005). The nuclear lamina has attracted the attention of researchers in the field of aging following the discovery of mutations in genes encoding protein components of these structures or factors that influence their maturation and dynamics and cause progeroid syndromes such as Hutchinson-Gilford syndrome and Nestor-Guillermo syndrome (SPHG and SPNG, respectively) (Cabanillas et al., 2011; De Sandre-Giovannoli et al., 2003; Eriksson et al., 2003). Alterations in nuclear lamina and production of an aberrant prelamin A isoform (otherwise called -progerin‖) are also detected in normal human aging (Ragnauth et al., 2010; Scaffidi and Misteli, 2006). Telomere dysfunction also increases progerin production in normal human fibroblasts in in vitro culture, suggesting additional links between telomere length maintenance and progerin expression in normal aging (Cao et al., 2011). In addition to these age-related changes in type A lamins, levels of type B1 lamins decrease during cell aging, suggesting their utility as a biomarker of this process (Freund et al., 2012; Shimi et al., 2011).

Animal and cellular models have facilitated the identification of stress-induced metabolic pathways that develop under the influence of disruption of nuclear lamina structure during SPXG. These pathways combine p53 activation (Varela et al., 2005), deregulation of the somatotropic axis (Marin˜ o et al., 2010) and depletion of adult stem cells (Espada et al., 2008; Scaffidi and Misteli, 2008). A reason to believe that abnormalities in nuclear laminin contribute to accelerated aging is provided by the fact that lowering prelamin A or progerin levels delays the onset of progeroid symptoms and increases longevity in mouse models of SPCG. This can be achieved by systemic administration of antisense oligonucleotides, farnesyltransferase inhibitors or a combination of statins and aminobisphosphonates (Osorio et al., 2011; Varela et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2006). Restoration of the somatotropic axis by hormone therapy or inhibition of NF-kB signalling also increases the lifespan of progeroid mice (Marin˜ o et al., 2010; Osorio et al., 2012). In addition, a strategy based on homologous recombination has been developed to eliminate LMNA gene mutations in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from SPCG patients. This principle holds great promise for cell therapy in the future (Liu et al., 2011b). Further studies are needed to confirm that enhancing nuclear architecture can delay normal aging.

In summary

There is abundant evidence that aging is accompanied by damage to the genome, and that its artificial damage can accelerate aging. It has been observed that enhancing the mechanisms that ensure proper chromosome segregation increases mammalian lifespan (Baker et al., 2013). Furthermore, in the particular case of progeria associated with nuclear architecture defects, there are proven therapeutic modalities that can delay premature aging. Similar remedies should be explored to find ways to influence other aspects of nuclear and mitochondrial genome stability, such as DNA repair, which may have a positive effect on normal aging (telomeres represent a special case and are discussed separately).

Shortening of telomeres

The accumulation of DNA damage with age randomly affects the genome, but chromosome regions such as telomeres are particularly susceptible to wear and tear with age (Blackburn et al., 2006) (Figure 2A). Replicative DNA polymerases lack the ability to fully replicate the terminal ends of linear DNA molecules, a function shared with the specialised DNA polymerase, also known as telomerase. However, most mammalian somatic cells do not express telomerase, leading to a progressively increasing loss of sequences at the ends of chromosomes that protect telomeres. Telomere shortening explains the limited proliferative capacity of some cell culture types grown in vitro, also known as replicative senescence phenomenon or Hayflick’s limit (Hayflick and Moorhead, 1961; Olovnikov, 1996). Indeed, ectopic expression of telomerase would be sufficient to confer immortality to lethal cells without inducing tumour transformation (Bodnar et al., 1998). Importantly, telomere shortening during normal aging has been observed in both humans and mice (Blasco, 2007).

Telomeres are associated with a characteristic multiprotein complex known as shelterin (Shelterin) (Palm and de Lange, 2008). The main function of the complex is to protect telomeres from DNA repair enzymes. Otherwise, telomeres will be ‘repaired’ as DNA breaks, leading to chromosome fusion. Due to limited DNA repair, damage accumulates in large amounts at telomeres and induces aging and/or apoptosis (Fumagalli et al., 2012; Hewitt et al., 2012).

Telomerase deficiency in humans is associated with early development of diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis, congenital dyskeratosis and aplastic anaemia, which include loss of regenerative abilities of various tissues (Armanios and Blackburn, 2012). Loss of telomeres’ protective “caps” and uncontrolled chromosome fusion can also occur when shelterin components malfunction (Palm and de Lange, 2008). Shelterin mutations have been found in some cases of aplastic anaemia and congenital dyskeratosis (Savage et al., 2008; Walne et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2011). When modelling cases of loss of function by shelterin components, a dramatic decrease in the regenerative capacity of tissues and accelerated aging is observed. This phenomenon can also be observed at normal telomere length (Martı´nez and Blasco, 2010).

Genetically modified animal models have helped to establish a link between telomere loss, cellular senescence and organismal aging. For example, mice with shortened telomeres live shorter and those with longer telomeres live longer (Armanios et al., 2009; Blasco et al., 1997; Herrera et al., 1999; Rudolph et al., 1999; Toma´ s-Loba et al., 2008). Recent discoveries also suggest that aging can be reversed by telomerase activation. In particular, early aging of telomerase-deficient mice can be prevented by genetic reactivation of their telomerase (Jaskelioff et al., 2011). In addition, normal physiological aging can be delayed in adult wild-type mice by systemic viral transduction of telomerase without increasing the likelihood of cancer (Bernardes de Jesus et al., 2012). A recent meta-analysis confirmed the existence of a correlation between mortality and short telomere length in humans, especially at a young age (Boonekamp et al., 2013).

In summary

Normal aging in mammals is accompanied by telomere shortening. Moreover, pathological telomere dysfunction accelerates aging in mice and humans, whereas experimental stimulation of telomerase is able to slow down aging in mice. Thus, this trait fulfils all the criteria of a key sign of aging.

Epigenetic alterations

A variety of epigenetic alterations occur throughout life in all cells and tissues (Talens et al., 2012) (Figure 2B). These alterations include changes in DNA methylation pattern, post-translational modification of histones and chromatin remodelling. Increased acetylation of histone H4K16, trimethylation of H4K20 or H3K4, and decreased methylation of H3K9 or H3K27 are age-associated features (Fraga and Esteller, 2007; Han and Brunet, 2012). The numerous enzyme systems responsible for the generation and maintenance of epigenetic patterns include DNA methyltransferases, histone acetylases, deacetylases, methylases, demethylases, and protein complexes involved in chromatin remodelling.

Histone modifications

Histone methylation fulfils the criteria for a key sign of aging in invertebrates. Deletion of components of histone methylation complexes (for H3K4 and for H3K27) increases lifespan in nematodes and flies, respectively (Greer et al., 2010; Siebold et al., 2010). In addition, inhibition of histone demethylases (for H3K27) can increase lifespan in worms by affecting components of key longevity pathways such as the insulin/IFR-1 signalling pathway (Jin et al., 2011). It is not entirely clear whether manipulation of histone-modifying enzymes can affect aging using solely epigenetic mechanisms overlaid on DNA repair and genome stability, or whether they affect through transcriptional changes affecting metabolic and signalling pathways outside the nucleus.

NAD-dependent protein deacetylases and ADP-ribosyl transferases from the sirtuin family are considered as potential factors that slow down aging. Interest in this family of proteins began with a series of studies in yeast, flies, and worms in which it was observed that a single sirtuin gene in these organisms, called Sir2, has remarkable longevity activity (Guarente, 2011). An increase in replicative longevity upon Sir2 overexpression was first reported in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Kaeberlein et al., 1999), and a similar effect was later observed in model invertebrate organisms when orthologues were overexpressed in worms (sir-2.1) and flies (dSir2) (Rogina and Helfand, 2004; Tissenbaum and Guarente, 2001). However, these findings have recently raised a number of questions due to a report showing that the observed increase in lifespan in worms and flies was due to significant differences in genetic context rather than overexpression of sir-2.1 or dSir2, respectively (Burnett et al., 2011). Indeed, careful reassessment showed that sir-2.1 overexpression leads to a moderate increase in lifespan only in C. elegans (Viswanathan and Guarente, 2011).

Some of the 7 mammalian sirtuin paralogues can influence various aspects of aging in mice (Houtkooper et al., 2012; Sebastia´ n et al., 2012). In particular, transgenic overexpression of SIRT1, which is the closest invertebrate homologue of Sir2 in mammals, improves overall fitness during aging but does not affect longevity (Herranz et al., 2010). The mechanisms that provide the beneficial effects of SIRT1 are complex and interrelated, and include increased genome stability (Oberdoerffer et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008) as well as enhanced metabolic efficiency (Nogueiras et al., 2012) (see ‘’Disruption of Nutrient Recognition‘’). Stronger evidence that sirtuins play a positive role in longevity has been obtained for SIRT6, which regulates genome stability, NF-kB signalling and glucose homeostasis via H3K9 deacetylation (Kanfi et al., 2010; Kawahara et al., 2009; Zhong et al., 2010). SIRT6-deficient mice age faster than control animals (Mostoslavsky et al., 2006), whereas male transgenic mice overexpressing SIRT6 have a longer lifespan than control animals, associated with decreased serum concentrations of IGF-1 and other components of the IGF-1 signalling cascade (Kanfi et al., 2012). Interestingly, the mitochondria-located sirtuin SIRT3 was found to be responsible for some of the beneficial effects of caloric restriction on longevity, although these effects did not develop due to histone modifications but rather due to deacetylation of mitochondrial proteins (Someya et al., 2010). More recently, SIRT3 overexpression has been shown to improve the regenerative abilities of senescent haematopoietic stem cells (Brown et al., 2013). Thus, in mammals, at least three members of the sirtuin family (SIRT1, SIRT3 and SIRT6) contribute to healthy aging.

DNA methylation

The relationship between DNA methylation and aging is controversial. Early work identified age-associated systemic hypomethylation, but subsequent analysis has shown that several loci, including those of various tumour suppressor genes and Polycomb target genes, are conversely over-methylated with age (Maegawa et al., 2010). Cells from patients and mice with progeria syndromes have the same patterns of DNA methylation and histone modifications as normally aging cells (Osorio et al. 2010; Shumaker et al. 2006). All these epigenetic defects or epimutations, accumulating with age, specifically affect stem cell behaviour and function (Pollina and Brunet, 2011) (see Stem cell depletion). However, there has been no direct experiment showing that the lifespan of an organism can be increased by altering DNA methylation patterns.

Chromatin remodelling

DNA- and histone-modifying enzymes act together with key chromosomal proteins, such as heterochromatin protein 1a (HP1a), and chromatin remodelling factors, such as Polycomb group proteins or the NuRD complex, whose levels decrease in normal and pathological cell aging (Pegoraro et al. 2009; Pollina and Brunet, 2011). In addition to the epigenetic modifications in histones and DNA methylation described above, alterations in these epigenetic factors determine changes in chromatin architecture such as global loss and redistribution of heterochromatin, which are hallmarks of aging (Oberdoerffer and Sinclair, 2007; Tsurumi and Li, 2012). The link between these chromatin changes and aging is supported by the discovery that loss-of-function mutant flies in HP1a have a shorter lifespan, whereas overexpression of this heterochromatin protein increases lifespan in flies and delays the deterioration of muscle function characteristic of aging (Larson et al. 2012).

The relationship between DNA repeat formation and chromosomal stability confirms the functional significance of epigenetic changes in chromatin during aging. In particular, heterochromatin assembly in pericentric regions requires trimethylation of histones H3K9 and H4K20, as well as HP1a binding, and maintains chromosomal stability (Schotta et al. 2004). Mammalian telomeric repeats are enriched in these chromatin modifications, indicating that chromosome ends assemble into heterochromatin domains (Blasco, 2007b; Gonzalo et al., 2006). Subtelomeric regions also exhibit features of constitutive heterochromatin, including trimethylation of histones H3K9 and H4K20, HP1a binding, and DNA hypermethylation. Thus, epigenetic alterations may directly interfere with the regulation of telomere length, one of the key hallmarks of aging.

Transcriptional changes

Increased transcriptional noise (Bahar et al., 2006) and aberrant mRNA synthesis and maturation (Harries et al., 2011; Nicholas et al., 2010) are inevitable companions of aging. Microarray comparisons of young and old tissues from several species have helped to detect accumulating transcriptional changes with age in genes encoding key components of inflammation, as well as mitochondrial and lysosome degradation (de Magalhaes et al., 2009). These age-related changes in transcription profile also affect non-coding RNAs that include a class of miRNAs (gero-miRNAs) that is associated with aging and affects lifespan by affecting components of signalling pathways that regulate lifespan or stem cell behaviour (Boulias and Horvitz, 2012; Toledano et al., 2012; Ugalde et al., 2011). Studies of gain- or loss-of-function mutations have confirmed the ability of some miRNAs to influence the lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster and C. elegans (Liu et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2012; Smith-Vikos and Slack, 2012).

Reversibility of epigenetic changes

Unlike DNA mutations, epigenetic changes are, at least theoretically, reversible, which makes it possible to create new anti-aging agents (Freije and Lopez-Otin, 2012; Rando and Chang, 2012). Restoration of physiological histone H4 acetylation using histone deacetylase inhibitors avoids the manifestation of age-related memory impairments in mice. This indicates that restoration of epigenetic impairments may have neuroprotective effects. Histone acetyltransferase inhibitors also reduce the outward manifestations of aging in progeroid mice and increase their lifespan (Krishnan et al., 2011). Moreover, the recent discovery of epigenetic inheritance of longevity across generations in C. elegans suggests that manipulation of specific chromatin modifications in parents may induce epigenetic memory of longevity in their offspring (Greer et al., 2011). Activators of histone deacetylases can presumably increase longevity in a fundamentally similar manner to inhibitors of histone acetyltransferases. Resveratrol has been studied in detail in relation to aging, and among its multiple mechanisms of action are increased SIRT1 activity and other effects associated with energy deficiency (see Mitochondrial Dysfunction).

In summary

There is abundant evidence to suggest that aging is accompanied by epigenetic changes that can induce progeroid syndromes in model organisms. SIRT6 provides an example of an epigenetically relevant enzyme, and its loss of activity due to mutation shortens mouse lifespan, while gain of activity increases it (Kanfi et al., 2012; Mostoslavsky et al., 2006). Taken together, these works suggest that understanding and processing the epigenome holds great promise for combating age-related pathologies and increasing healthy lifespan.

Proteostasis disorder

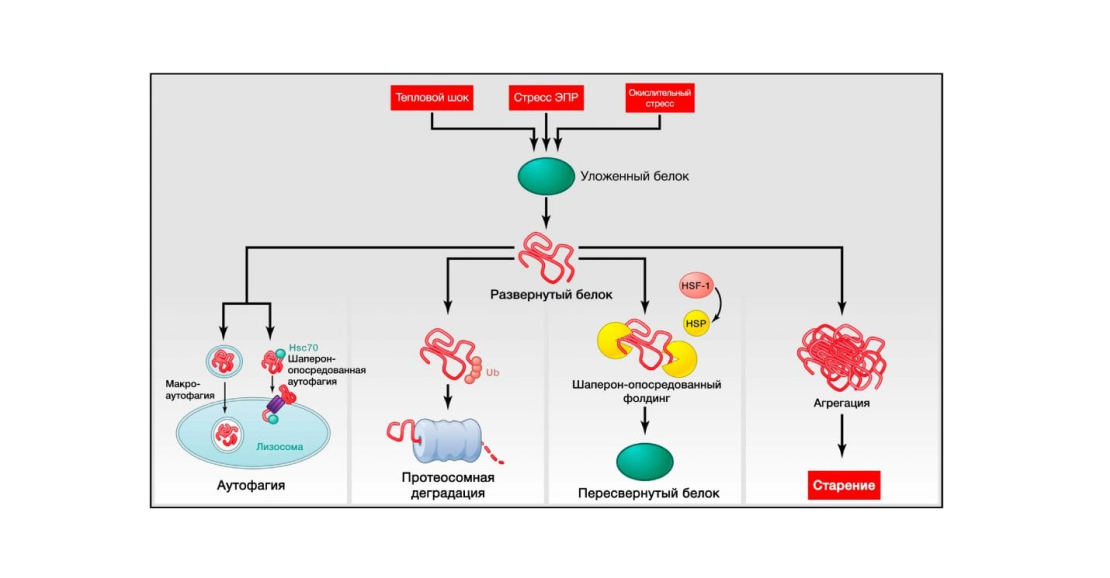

Aging and some age-related diseases are associated with impaired protein homeostasis or proteostasis (Powers et al., 2009) (Figure 3). All cells successfully utilise a set of quality control mechanisms aimed at maintaining the stability and functionality of their proteomes. Proteostasis includes mechanisms for stabilising properly stacked proteins, of which the most well-known is the heat shock protein system, as well as mechanisms for protein degradation by proteosomes or lysosomes (Hartl et al., 2011; Koga et al., 2011; Mizushima et al., 2008). In addition, there are regulators of age-dependent proteotoxicity, such as MOAG-4, that act by alternative pathways other than molecular chaperones and proteases (van Ham et al., 2010). All these systems act in concert to repair the structure of a misfolded polypeptide or degrade it, preventing the accumulation of damaged components and ensuring that intracellular proteins are constantly renewed. Many works have shown that proteostasis is impaired in aging (Koga et al., 2011). In addition, constant expression of misfolded, misfolded or aggregated proteins contributes to the development of some age-related pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and cataracts (Powers et al., 2009).

Figure 3: Disruption of proteostasis. Source: Journal of Cell

Endogenous and exogenous stress causes proteins to unfold (or disrupts their proper stacking during synthesis). Unfolded proteins usually undergo refolding by heat shock proteins (HSPs) or serve as targets of degradation by ubiquitin-proteosomal or lysosomal (autophagic) pathways. Autophagic pathways include recognition of unfolded proteins by the chaperone Hsc70 and their subsequent transfer to lysosomes (chaperone-mediated autophagy) or destruction of damaged proteins and organelles in autophagosomes that later fuse with lysosomes (macroautophagy). Failure to refold or degrade unfolded proteins can lead to their accumulation and aggregation, resulting in proteotoxic effects.

Chaperone-mediated folding and protein stability

The stress-induced synthesis of cytosolic and organelle-specific chaperones is significantly impaired in aging (Calderwood et al., 2009). Numerous studies on model organisms confirm the effects of impaired chaperone function on longevity. In particular, transgenic worms and flies overexpressing chaperones are long-lived (Morrow et al., 2004; Wlaker and Lithgow., 2003). Mutant mice deficient in chaperones from the heat shock protein family age more rapidly, whereas long-lived mouse lines show significant increases in the expression of several heat shock proteins (Min et al., 2008; Swindell et al., 2009). Moreover, activation of a key regulator of the heat shock response, the transcription factor HSF-1, increases longevity and thermotolerance in nematodes (Chiang et al., 2012; Hsu et al., 2003). At the same time, amyloid binding components may also maintain proteostasis during aging and increase lifespan (Alavez et al., 2011). In mammalian cells, deacetylation of HSF-1 by the SIRT1 protein causes transactivation of heat shock genes such as Hsp70, whereas inhibition of SIRT1 attenuates the response to heat shock (Westerheide et al., 2009).

Proteolytic systems

The activity of two major proteolytic systems involved in protein quality control, the lysosomal autophagy system and the ubiquitin-proteasome system, decreases with aging (Rubinsztein et al., 2011; Tomaru et al., 2012), confirming the specific role of proteostasis in aging.

Regarding autophagy, transgenic mice with an extra copy of the chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor LAMP2a retain liver function well with age and do not experience an age-dependent decline in autophagy activity (Zhang and Cuervo, 2008). The introduction of chemical inducers of macroautophagy (a different type of autophagy from chaperone-mediated autophagy) has attracted extraordinary interest following the discovery that continuous or intermittent administration of the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, can increase the lifespan of mature mice (Blagosklonny, 2011; Harrison et al., 2009). Notably, rapamycin affects several aspects of aging in mice (Wilkinson et al., 2012). The lifespan-enhancing effect of rapamycin is strictly dependent on the induction of autophagy in yeast, worms and flies (Bjedov et al., 2010; Rubinsztein et al., 2011). However, similar findings regarding the effects of rapamycin on mammalian aging have not yet been made, and other mechanisms (see Nutrient Recognition Disorder), such as inhibition of ribosomal S6 protein kinase 1 (S6K1), which is involved in protein synthesis (Selman et al., 2009), may explain the effects of rapamycin on lifespan. Spermidine, another macroautophagy inducer, which unlike rapamycin has no immunosuppressive side effect, also prolongs the life of yeast, flies and worms by inducing autophagy (Eisenberg et al., 2009). Supplementation of a spermidine-containing polyamine mixture in the diet or the provision of polyamine-producing gut flora increases longevity in mice (Matsumoto et al., 2011; Soda et al., 2009). Supplementation with ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids also increases lifespan in flies by activating autophagy (O’Rourke et al., 2013).

With respect to proteasomes, activation of EGF signalling lengthens the lifespan of nematodes by increasing the expression of various components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Liu et al., 2011a). Similarly, enhancement of proteasomal activity by deubiquitylase inhibitors or proteasomal activators accelerates the removal of toxic proteins in human cell culture (Lee et al., 2010) and increases replicative lifespan in yeast (Kruegel et al., 2011). In addition increased expression of the proteasomal subunit RPN-6 by the FOXO family transcription factor DAF-16, increases resistance to proteotoxic stress and lifespan in C. elegans (Vilchez et al., 2012).

In summary

There is evidence that aging is associated with defects in the proteostasis system, and its experimental disruption leads to the development of age-related pathologies. There are also impressive examples of genetic manipulations that improve proteostasis and delay aging in mammals (Zhang and Cuervo, 2008).

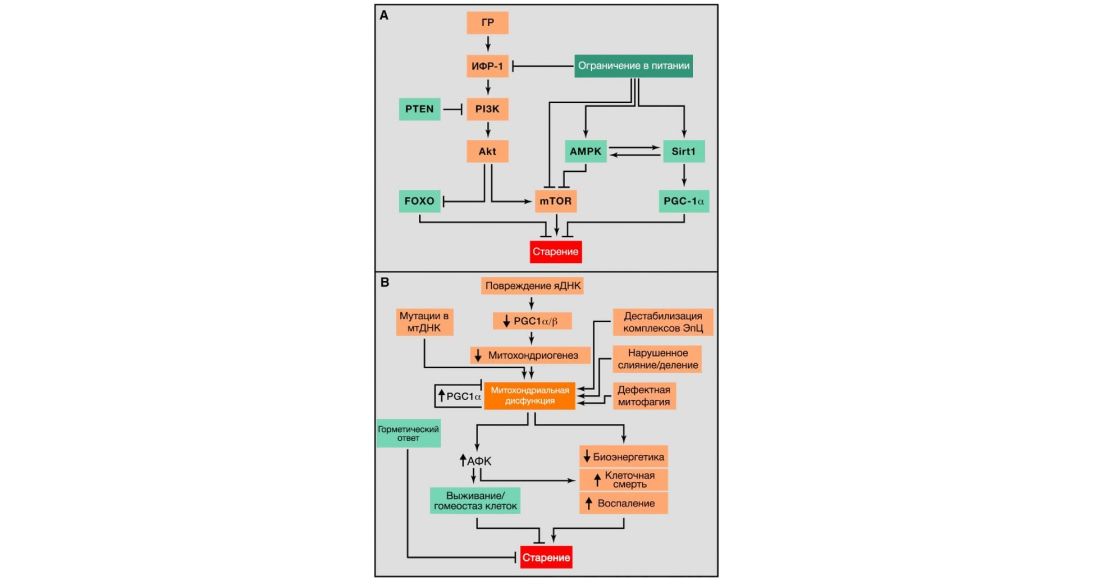

Impaired nutrient recognition

The mammalian somatotropic axis includes growth hormone (GH), which is produced by the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, and its secondary mediator, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which is produced in response to GH by many cell types, most commonly hepatocytes. The intracellular signalling pathway of IGF-1 is the same as that of insulin, which informs cells of the presence of glucose. For this reason, IGF-1 and insulin signalling is known as the ‘IGF-1 and insulin signalling’ (IIS) molecular pathway. Notably, the IIS pathway is the most evolutionarily conserved metabolic pathway controlling aging, among its many targets are the FOXO family transcription factors and mTOR complex proteins, which are also involved in aging and conserved by evolution (Barzilai et al., 2012; Fontana et al., 2010; Kenyon, 2010). Genetic polymorphisms and mutations that impair the functions of GH, IGF-1 receptor, insulin receptor or their intracellular effectors such as AKT, mTOR and FOXO are associated with longevity in both humans and model organisms, further illustrating the significant impact of trophic and bioenergetic pathways on longevity (Barzilai et al., 2012; Fontana et al., 2010; Kenyon, 2010) (Figure 4A).

Confirming the relevance of impaired nutrient recognition as a key hallmark of aging, dietary restriction (DR) increases longevity and healthy lifespan in all eukaryotic organisms studied, including lower primates (Colman et al., 2009; Fontana er al., 2010; Mattison et al., 2012).

Insulin and IGF-1 signalling pathways

Numerous genetic manipulations that disrupt signalling at different levels of the ISI molecular pathway increase longevity in worms, flies and mice (Fontana et al., 2010). Genetic analyses have shown that this metabolic pathway mediates part of the beneficial effects of OA on longevity in worms and flies (Fontana et al., 2010). Among the downstream effectors in the IIS signalling pathway, the transcription factor FOXO has the greatest effect on longevity in worms and flies (Kenyon et al., 1993; Slack et al., 2011). There are 4 members of the FOXO family in mice, but the effects of their overexpression on longevity and their role in regulating the increase in healthy longevity by reducing IIS activity have not yet been established.

Mouse FOXO1 is required for OD tumour suppressor effects (Yamaza et al., 2010), but it is unknown whether this factor is involved in OD-mediated longevity extension. As recently shown, mice overexpressing the tumour suppressor PTEN exhibit an overall decrease in the activity of the IIS signalling pathway and an increase in energy associated with improved mitochondrial oxidation and increased brown fat activity (Garcia-Cao et al., 2012; Ortega-Molina et al., 2012). Lines of other mouse models with reduced PI activity, Pten overexpressing mice, and mice with hypomorphic PI3K have longer lifespan (Foukas et al., 2013; Ortega-Molina et al., 2012).

Paradoxically, GH and IGF-1 levels are reduced both during normal aging and in mouse models with premature aging (Schumacher et al., 2008). Thus, decreased ISI activity is a common characteristic of normal and accelerated aging, whereas persistently reduced ISI activity increases lifespan. These seemingly contradictory observations can be explained within the framework of one theory, according to which reduced IIS activity reflects a protective response aimed at minimising cellular growth and metabolism in the context of systemic damage (Garinis et al., 2008). According to this view, organisms with constitutively reduced IIS activity may survive longer because they have a lower rate of cellular growth and metabolism and, as a consequence, a lower rate of cellular damage accumulation. For the same reason, physiologically or pathologically aged organisms tend to reduce IIS activity in an attempt to increase longevity. However, defence responses directed against ageing themselves have the risk of becoming harmful and accelerating it, a concept we will return to in the following sections. Thus, extremely low levels of ISI are incompatible with life, as exemplified by null mutations of PI3K or AKT kinases, which are lethal as early as the embryonic stage (Renner and Camero, 2009). Also in progeroid mice with very low levels of IGF-1 there were cases when supplementation of IGF-1 could slow down premature aging (Marino et al., 2010).

Figure 4: Metabolic alterations. Source: Journal of Cell

(A) Disruption of nutrient recognition. Overview of the somatotropic axis involving growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signalling pathways and its relationship between nutritional restriction and ageing. Aging-promoting molecules are highlighted in orange, aging-delaying molecules are highlighted in green.

(B) Mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondrial function is impaired due to age-associated accumulation of mutations in mtDNA that impair mitochondriogenesis, destabilise the electron transfer chain (ETC), leading to altered mitochondrial dynamics or misjudgment of mitophagy quality. Stress-induced signalling and mitochondrial dysfunction lead to an increase in AFCs, which, at their relatively low concentration, leads to activation of survival signalling and restoration of cellular homeostasis, but when prolonged and/or high levels of AFCs, leads to senescence. Similarly, mild mitochondrial damage can induce a hormetic response (mitohormesis) that triggers adaptive compensatory responses.

Other nutrient recognition systems: mTOR, AMPK and sirtuins

In addition to the molecular pathway of EIS, which is involved in the control of glucose metabolism, the focus of current research is on three other interrelated nutrient recognition systems: mTOR, which recognises high concentrations of amino acids; AMPK, which responds to low-energy states by detecting high levels of AMP; and sirtuins, which respond to low-energy states by recognising high levels of NAD+ (Houtkooper et al., 2010) (Figure 4A) (Figure 4A).

The mTOR kinase is part of two multiprotein complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2, which regulate virtually all aspects of anabolism (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Genetic deactivation of mTORC1 increases lifespan and attenuates the beneficial effects of OA in yeast, worms and flies, suggesting that inhibition of mTOR phenocopies OA (Johnson et al., 2013). In mice, rapamycin administration increases lifespan, it is considered the most reliable chemical agent for life extension in mammals (Harrison et al., 2009). Genetically modified mice with low mTORC1 activity but normal mTORC2 activity show increased longevity (Lamming et al., 2012), in addition, mice deficient in S6K1 (a major substrate of mTORC1) are also long-lived (Selman et al., 2009). Thus, mTORC1/S6K1 deactivation is a major mediator of mammalian longevity in relation to mTOR. Moreover, mTOR activity in mouse hypothalamic neurons increases with age, contributing to age-related obesity, which can be treated by direct infusion of rapamycin into the hypothalamus (Yang et al., 2012). These observations, including the ISI signalling pathway, suggest that excess trophic and anabolic activities mediated by these metabolic pathways are major factors accelerating ageing. And while inhibition of TOR activity has obvious beneficial effects on the aging process, it also has undesirable side effects such as impaired wound healing, insulin resistance, cataracts and testicular degeneration in mice (Wilkinson et al., 2012). Therefore, in order to understand at what level the beneficial and damaging effects of TOR inhibition can still be separated, it will be important to identify the mechanisms involved.

The other two nutrient recognition systems, AMPK and sirtuins, act in the opposite direction with respect to ISIS and mTOR: they signal nutrient deficiency and catabolism rather than nutrient availability and anabolism. Accordingly, their increased expression promotes healthy aging. AMPK activation has multiple effects on metabolism and, remarkably, inactivates mTORC1 (Alers et al., 2012). There is evidence to suggest that AMPK activation following metformin administration can lead to increased longevity in worms and mice (Anisimov et al., 2011; Mair et al., 2011; Onken and Driscoll, 2010). The role of sirtuins in the regulation of lifespan has been stipulated above (see Epigenetic Alterations). In addition, SIRT1 can deacetylate and activate PPARg coactivator 1a (PGC-1a) (Rodgers et al., 2005). PGC-1a regulates a complex metabolic response that includes mitochondriogenesis, enhanced antioxidant defence and enhanced fatty acid oxidation (Fernandez-Marcos and Auwerx, 2011). Furthermore, SIRT1 and AMPK may be included in a positive feedback loop, integrating both sensors of low-energy states into a single system (Price et al., 2012).

In summary

All currently available evidence supports that anabolic signalling accelerates aging and catabolic signalling increases lifespan (Fontana et al., 2010). Furthermore, pharmacological manipulations that mimic a state of limited nutrient availability, such as the administration of rapamycin, can increase lifespan in mice (Harrison et al., 2009).

Mitochondrial dysfunction

In aging cells and organisms, the efficiency of the respiratory chain typically decreases, and as a consequence, electron leakage increases and ATP generation decreases (Green et al., 2011) (Figure 4B). It has long been thought that there is a link between mitochondrial dysfunction and aging, but determining the details of such a link remains a major challenge in aging research.

Active forms of oxygen

The mitochondrial free-radical theory of aging suggests that in aging there is a progressive dysfunction of mitochondria, which leads to increased production of AFCs, which in turn cause further deterioration of mitochondrial function and global cellular damage (Harman, 1965). Numerous data support the role of AFCs in aging, but we will focus on studies from the last 5 years that have led to a significant reevaluation of the mitochondrial free-radical theory of aging (Hekimi et al., 2011). Of particular importance was the unexpected observation that elevated AFCs can increase lifespan in yeast and C. elegans (Doonan et al., 2008; Mesquita et al., 2010; Van Raamsdonk and Hekimi, 2009). It has also been observed that genetic manipulations in mice that lead to increased AFC in mitochondria and oxidative damage do not accelerate aging (Van Remmen et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2009), and mice with enhanced antioxidant defences do not live longer (Pe´rez et al., 2009), and finally, genetic manipulations that disrupt mitochondrial function do not cause an increase in AFC-dependent aging. (Edgar et al., 2009; Hiona et al., 2010; Kujoth et al., 2005; Trifunovic et al., 2004; Vermulst et al., 2008). These and other data have paved the way for rethinking the role of AFCs in aging processes (Ristow and Schmeisser, 2011). Indeed, in the field of intracellular signalling, which is developing in parallel and autonomously from work on the damaging effects of AFCs, much evidence has accumulated in favour of a role for AFCs in triggering proliferation and survival in response to physiological signals and stress conditions (Sena and Chandel, 2012). The two lines of evidence can be reconciled by considering AFC as a stress-induced survival signal conceptually similar to AMP or NAD+ (see Nutrient Recognition Disorder). In this respect, the primary effect of AFC would be to activate compensatory homeostatic responses. With increasing chronological age, cellular stress and damage increases, and in parallel, in an attempt to survive, AFC levels increase. Once a certain threshold is reached, AFCs cease to fulfil their homeostatic functions and instead exacerbate, rather than mitigate, age-associated damage (Hekimi et al., 2011). This new conceptual model may help to unify the seemingly contradictory data on the positive, negative, and neutral effects of AFCs on aging.

Mitochondrial integrity and biogenesis

Dysfunctional mitochondria may contribute to aging independently of AFC, as evidenced by experiments with mice deficient in gamma-DNA polymerase (Edgar et al., 2009; Hiona et al., 2010) (see ‘Genome instability’). Many mechanisms may be involved; for example, mitochondrial dysfunction may affect apoptotic signalling by increasing the propensity of mitochondria to permeabilise in response to stress (Kroemer et al., 2007) and triggering inflammatory responses by providing AFC-mediated and/or permeabilisation-facilitated activation of inflammosomes (Green et al., 2011). Mitochondrial dysfunction can also directly affect cell signalling and interactions between organelles, affecting the interaction region of the outer mitochondrial membrane and endoplasmic reticulum (Raffaello and Rizzuto, 2011).

Reduced mitochondrial bioenergetic efficiency with age may result from many similar mechanisms, including reduced mitochondrial biogenesis, for example due to telomere shortening in telomerase-deficient mice, followed by p53-mediated repression of PGC-1a and PGC-1b (Sahin and DePinho, 2012). Impairment of mitochondrial function also occurs during physiological aging in wild-type mice and can be partially restored by telomerase activation (Bernardes de Jesus et al., 2012). SIRT1 regulates mitochondrial biogenesis through a process involving the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1a (Rodgers et al., 2005) and the removal of damaged mitochondria during autophagy (Lee et al., 2008). SIRT3, which is a major mitochondrial deacetylase (Lombard et al., 2007), targets many enzymes involved in energy metabolism, including components of the respiratory chain, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, ketogenesis and fatty acid beta-oxidation (Giralt and Villarroya, 2012). SIRT3 may also directly control AFC production by deacetylating manganese superoxide dismutase, a major mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme (Qiu et al., 2010; Tao et al., 2010). Taken together, these observations support the idea that telomeres and sirtuins may control mitochondrial function and thus play a protective role against age-related diseases.

Other causal mechanisms of defective bioenergetics include accumulation of mutations and deletions in mtDNA, oxidation of mitochondrial proteins, destabilisation of the macromolecular organisation of respiratory chain (super)complexes, and changes in the lipid composition of mitochondrial membranes, changes in mitochondrial dynamics resulting from an imbalance between fission and fusion and poor quality control of mitophagy, an organelle-specific form of macroautophagy that captures dysfunctional mitochondria for proteolytic degradation (Wang and Klionsky, 2011). The combination of increased damage and reduced mitochondrial renewal resulting from reduced biogenesis and impaired removal of degradation products may contribute to aging (Figure 4B).

Interestingly, endurance exercise and intermittent dietary restriction may increase healthy lifespan by protecting mitochondria from degeneration (Castello et al., 2011; Safdar et al., 2011). One would like to think that these beneficial effects are at least partially mediated by the induction of autophagy, as both endurance exercise and periodic dietary restriction serve as potent triggers of it (Rubinsztein et al., 2011). However, autophagy induction is not the only mechanism by which a healthy lifestyle can slow down aging, as additional molecular pathways leading to longevity may be activated when a certain dietary restriction regime is followed (Kenyon, 2010).

Mytogormesis

Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging is also associated with hormesis, a concept on which several lines of research have converged (Calabrese et al., 2011). According to this concept, the administration of mildly toxic drugs triggers favourable compensatory responses that not only repair trigger damage but also make the cell more resistant to damage. Thus, although severe mitochondrial dysfunction leads to pathology, a small respiratory deficit can increase lifespan, possibly through hormetic effects (Haigis and Yankner, 2010). Hormetic responses can trigger a mitochondrial defence response both in the tissue with defective mitochondria itself and in deleted tissues, as has been shown in C. elegans (Durieux et al., 2011). There is strong evidence that compounds such as metformin and resveratrol are weak mitochondrial poisons that induce a low energy state characterised by an increase in AMP and AMPK activation (Hawley et al., 2010). Importantly, metformin increases the lifespan of C. elegans by inducing a compensatory stress response mediated by AMPK and the master regulator of the antioxidant system NRF2 (Onken and Driscoll, 2010). Recent studies have also shown that metformin slows aging in worms by altering folate and methionine metabolism in their gut microbiome (Cabreiro et al., 2013). Regarding mammals, metformin can increase the lifespan of mice if administered from the first months of life (Anisimov et al., 2011). Regarding resveratrol and the sirtuin activator SRT1720, there is strong evidence that through a PGC-1a dependent mechanism they protect against metabolic damage and improve mitochondrial respiration (Baur et al., 2006; Feige et al., 2008; Lagouge et al., 2006; Minor et al., 2011), although under normal nutritional conditions resveratrol is unable to increase mouse lifespan (Pearson et al., 2008; Strong et al., 2013). The effect of PGC-1a on longevity is further supported by the observation that its overexpression, associated with improved mitochondrial activity, increases lifespan in Drosophila (Rera et al., 2011). Finally, uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation processes in mitochondria, both genetically, through overexpression of UCP1 protein, and by administration of the chemical uncoupler 2,4-dinitrophenol, can increase lifespan in flies and mice (Caldeira da Silva et al., 2008; Fridell et al., 2009; Gates et al., 2007; Mookerjee et al., 2010).

In summary

Mitochondrial functioning has a significant impact on aging processes. Mitochondrial dysfunction in mammals can accelerate them (Kujoth et al., 2015; Trifunovic et al., 2004; Vermulst et al., 2008), but it remains unclear whether increased mitochondrial function in mammals, such as in mitohormesis, provides an increase in longevity, although evidence suggests that it does.

Cellular aging

Cell senescence can be defined as the cessation of cell division with characteristic phenotype changes (Campisi and d’Adda di Fagagagna, 2007; Collado et al., 2007; Kuilman et al., 2010) (Figure 5A). This phenomenon was originally described by Hayflick in sequentially crossed cultures of human fibroblasts (Hayflick and Moorhead, 1961). Today we know that the senescence observed by Hayflick was caused by telomere shortening (Bodnar et al., 1998), but there are other age-associated stimuli independently triggering senescence. Foremost among these are damage to non-telomeric DNA regions and depression of the INK4/ARF locus, which progress with chronological aging and are also capable of inducing senescence of cells (Collado et al., 2007). The accumulation of senescent cells in senescent tissues is assessed by indirect markers such as DNA damage. In some studies, senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SABG) is determined to detect senescent cells in tissues (Dimri et al., 1995). Of note, in a detailed parallel determination of SABG and DNA damage in mouse liver, the total number of senescent cells was ~8% in a young mouse and ~17% in a very old mouse (Wang et al., 2009). Similar results were obtained for skin, lung and spleen, but no changes were observed in heart, skeletal muscle and kidney (Wang et al., 2009). Based on these data, it can be argued that senescence is not peculiar to all tissues of ageing organisms. In the case of senescent tumour cells, there is indisputable evidence that they are under strict immune surveillance and are efficiently removed by phagocytosis (Hoenicke and Zender, 2012; Kang et al., 2011; Xue et al., 2007). Presumably, senescent cell accumulation during aging may be characterised by an increased rate of senescent cell generation and/or a decreased rate of senescent cell removal, e.g. due to an impaired immune response.

Since the number of senescent cells increases with aging, it is assumed that senescence makes some contribution to aging. However, this viewpoint underestimates the presumed main role of senescentness – preventing the spread of damaged cells and triggering their destruction by the immune system. Thus, it is possible that senescence is an important compensatory mechanism that spares tissues from damaged and potentially oncogenic cells. This cellular checkpoint, however, requires an efficient replacement system to restore cell numbers, involving the removal of senescent cells and the mobilisation of progenitor cells. As the organism ages, this cycle may become inefficient, or the regenerative capacity of progenitor cells may be depleted, ultimately leading to increased damage that contributes to aging (Image 5A).

In recent years, there has been increasing attention to the fact that senescent cells undergo significant alterations in their secretome, which becomes particularly abundant in pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases and is often referred to as the ‘senescence-associated secretory phenotype’ (Kuilman et al., 2010; Rodier and Campisi, 2011). This pro-inflammatory secretome may contribute to aging (see ‘Intercellular communication’).

Figure 5. Cell senescence, stem cell pool depletion and altered intercellular interaction. Source: Journal of Cell

(A) Cell senescence. In young organisms, cell senescence prevents the proliferation of damaged cells, thus preventing cancer development and promoting normal tissue homeostasis. In old organisms, the spreading damage and incomplete clearance of senescent cells leads to their accumulation, resulting in a host of adverse effects that promote senescence.

(B) Stem cell depletion. The image shows the effects of depletion of haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), myosatellite cells and intestinal epithelial stem cells (ESCs).

(C) Altered intercellular interaction. Aging-related examples of intercellular interaction changes.

INK4a/ARF locus and p53

In addition to DNA damage, one of the stressors associated with aging is excess mitogenic signalling. A recent report lists 50 oncogenic and mitogenic alterations that can trigger senescence (Gorgoulis and Halazonetis, 2010). The number of mechanisms that trigger senescence in response to multiple oncogenic lesions has also grown, but the originally identified p16INK4a/Rb and p19ARF/p53 metabolic pathways remain the most important (Serrano et al., 1997). The relevance of these molecular pathways in aging becomes even more significant when one considers that in almost all human and mouse tissues analysed, p16INK4a (and to a lesser extent p19ARF) levels correlate with chronological age (Krishnamurthy et al., 2004; Ressler et al., 2006). It is the only known gene whose expression among such a diversity of tissues and species correlates so strongly with chronological aging, and this expression in old tissue can be, on average, up to 10-fold higher than in young tissue. Both p16INK4a and p19ARF are encoded by the same genetic locus INK4a/ARF. A recent meta-analysis of more than 300 full genome association studies (FGAs) showed that the INK4a/ARF locus is genetically associated with the greatest number of age-associated pathologies, including several types of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, glaucoma, and Alzheimer’s disease (Jeck et al., 2012). These observations suggest that the INK4a/ARF locus is the most studied genetic factor controlling human aging and the development of age-related pathologies. An important question remains unresolved as to whether disease-associated INK4a/ARF alleles encode acquisition or loss of function.

The critical role of p16INK4a and p53 in inducing cellular senescence suggests that p16INK4a- or p53-induced senescence contributes to physiological aging. According to this view, the senescence-inducing activity of p16INK4a and p53 is a reasonable payment for their involvement in tumour growth suppression. This is supported by the fact that mutant mice with premature senescence due to excessive and continuous damage have high levels of senescence, but their progeroid phenotype is improved when p16INK4a or p53 is deleted. The same occurs in BRCA1-deficient mice (Cao et al., 2003), model mice with PSCH (Varela et al., 2005) and mice with a chromosome stability defect due to a hypomorphic BubR1 mutation (Baker et al., 2011). However, other data suggest a more complex model. In contrast to the putative role of these genes in aging, mice with a small systemic increase in expression of the tumour suppressors p16INK4a, p19ARF or p53 show an increased lifespan that is not associated with a lower likelihood of developing cancer (Matheu et al., 2007, 2009). Also, deletion of p53 impairs the phenotype of some progeroid mutant mice (Begus-Nahrmann et al., 2009; Murga et al., 2009; Ruzankina et al., 2009). As in the case discussed above senescence, activation of p53 and INK4a/ARF can be seen as a favourable compensatory response aimed at preventing the proliferation of damaged cells and the consequences of this proliferation in the form of senescence and cancer. However, when damage is too extensive, the regenerative capacity of tissues may be depleted or suppressed, and under these critical conditions, p53 and INK4a/ARF responses may become detrimental and accelerate senescence.

In summary

We hypothesise that cellular senescence is an appropriate compensatory response to damage that becomes deleterious and accelerates ageing when tissues lose their regenerative potential. Taking these aspects into account, it is not possible to unequivocally answer the question whether cellular senescence satisfies the third criterion of a key attribute. Moderate stimulation of senescent-inducing metabolic pathways of tumour suppression can increase lifespan (Matheu et al., 2007, 2009), while at the same time, deletion of senescent cells in an experimental model of progeria slows the development of age-related pathologies (Baker et al., 2011). Thus, both interventions, which are fundamentally opposite, have the potential to increase healthy life expectancy.

Cellular aging

A decline in the regenerative potential of tissues is one of the most obvious characteristics of ageing (Image 5B). For example, haematopoiesis declines with age, leading to reduced production of adaptive immune cells – a process termed immunoaging – and an increased risk of anaemia and myeloid malignancies (Shaw et al., 2010). Such functional loss of stem cells has been found in virtually all adult stem cell compartments, including mouse forebrain (Molofsky et al., 2006), bone (Gruber et al., 2006) and muscle tissue (Conboy and Rando, 2012). Studies in old mice have found a decrease in haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) cell cycle activity – old HSCs underwent fewer cell divisions than young HSCs (Rossi et al., 2007). The decrease correlates with the accumulation of DNA damage (Rossi et al., 2007)and with the overexpression of cell cycle inhibitor proteins such as p16INK4a (Janzen et al., 2006). In fact, aged INK4a-/- HSCs are better engrafted and have higher cell cycle activity compared to aged wild-type HSCs (Janzen et al., 2006). Telomere shortening with aging is also an important reason for the decline in stem cell functions and their number in many tissues (Flores et al., 2005; Sharpless and DePinho, 2007). All these are just some examples of a huge system of reactions in which the deterioration of stem cell function and reduction of stem cell numbers is a consequence of the integration of many different lesions.

Although reduced proliferation of stem and progenitor cells is obviously detrimental to the long-term maintenance of body function, their excessive proliferation can also be harmful by accelerating the depletion of their cellular niche. The importance of stem cell quiescence for long-term maintenance of their functionality was convincingly demonstrated on the example of Drosophila intestinal stem cells, whose excessive proliferation leads to exhaustion and premature aging (Rera et al., 2011). A similar situation is found in p21-null mice, which exhibit premature depletion of HSCs and neural stem cells (Cheng et al., 2000; Kippin et al., 2005). In this regard, the induction of INK4a during aging (see Cell senescence) and the decrease in serum IGF-1 (see Nutrient recognition impairment) may reflect the body’s attempt to preserve stem cell resting. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that increased FGF2 signalling activity in the old muscle stem cell niche leads to quiescence and ultimately to stem cell exhaustion and reduced regeneration capacity, whereas suppression of this signalling prevents this defect (Chakkalakal et al., 2012). This holds promise for creating strategies aimed at inhibiting FGF2 signalling that will reduce stem cell depletion during ageing. By the same token, OP improves intestinal and muscle stem cell function (Cerletti et al., 2012; Yilmaz et al., 2012).

An important issue is to determine the role of intracellular and extracellular molecular pathways in reducing stem cell function (Conboy and Rando, 2012). Emerging work argues in favour of the latter. In particular, transplantation of stem cells derived from the muscle of young mice into progeroid mice increases longevity and reduces degenerative changes in these animals even in tissues in which donor cells are not found, suggesting that their therapeutic effect may be due to the systemic action of secreted factors (Lavasani et al., 2012). Moreover, parabiosis experiments have shown that reduced neural and muscle stem cell functions can be restored by systemic factors derived from young mice (Conboy et al., 2005; Villeda et al., 2011).

Pharmacological ways to improve stem cell function are also being investigated. For example, inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin can slow aging by improving proteostasis (see Disrupted proteostasis) and, by affecting substance recognition (see Disrupted nutrient recognition), can improve epidermal, haematopoietic and intestinal stem cell function (Castilho et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2009; Yilmaz et al., 2012). This illustrates the complexity in understanding the basis of the mechanisms of rapamycin’s anti-ageing activity and highlights the interconnectedness of the various key hallmarks of ageing discussed here. It is also worth noting the possibility of rejuvenating human senescent cells by pharmacological inhibition of the GTPase CDC42, whose activity is increased in ageing HSCs (Florian et al., 2012).

In summary

Stem cell depletion is a consequence of many different age-associated lesions, and is likely one of the major causes of tissue and organismal aging. Recent promising studies suggest that stem cell rejuvenation may reversibly affect the aging phenotype at the organismal level (Rando and Chang, 2012).

Altered intercellular communication

In addition to cell autonomous changes, ageing also involves changes at the level of intercellular communication: endocrine, neuroendocrine or neural (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012; Rando and Chang, 2012; Russell and Kahn, 2007; Zhang et al., 2013) (Image 5C). Thus, the regulation of neurohormonal signalling (e.g., renin-angiotensin, adrenergic, insulin-IFR1 signalling) tends to be impaired with aging as inflammatory responses increase, immune surveillance for pathogens and pre-tumour cells decreases, and the composition of the peri- and extracellular environment changes.

Inflammation

An important age-associated change in intercellular communication is ‘inflammaging,’ i.e., the sluggish proinflammatory phenotype that accompanies aging in mammals (Salminen et al., 2012). Inflammaaging can result from many causes, such as the accumulation of pro-inflammatory tissue damage, the inability of an increasingly weakened immune system to effectively remove pathogens and dysfunctional body cells, the propensity of senescent cells to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (see ‘Cellular Senescence’), increased activation of the transcription factor NF-kB, or impairments in the autophagy process (Salminen et al., 2012). These alterations lead to increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammosome and other pro-inflammatory pathways, ultimately leading to increased production of IL-1b, tumour necrosis factor and interferons (Green et al., 2011; Salminen et al., 2012). Inflammation has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes, two conditions that in the human population correlate with, as well as exacerbate, aging (Barzilai et al., 2012). Similarly, the pathological inflammatory response plays a critical role in the development of atherosclerosis (Tabas, 2010). The recent discovery that age-related inflammation suppresses epidermal stem cell function (Doles et al., 2012) confirms the complex relationship between various key features that enhance the aging process. In parallel to inflammation, the function of the adaptive immune system declines (Deeks, 2011). This immunosenescence may, at a systemic level, exacerbate the aging phenotype due to the inability of the immune system to remove infectious agents, infected cells and cells on the verge of tumour transformation. Moreover, one of the functions of the immune system is to recognise and remove senescent cells (see stem cell depletion) as well as hyperploid cells that accumulate in ageing tissues and in pre-tumour states (Davoli and de Lange, 2011; Senovilla et al., 2012).

Figure 6. Functional relationships between aging traits. Source: Cell Journal

The nine described signs of aging are grouped into three categories.

(Top) Signs that are believed to be the primary causes of cellular damage.

(Middle) Signs thought to be part of compensatory or antagonistic responses to damage. These responses are initially aimed at reducing damage, but eventually, with chronic or intense exposure, lead to damage.

(Basis) Integrative traits that are the end result of traits from the previous two groups and are ultimately responsible for the decline in function associated with aging.

Global studies on the transcriptome profile of aging tissues have emphasised the specific role of inflammatory metabolic pathways in the aging process (de Magalha˜ es et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2012). Over-activation of the NF-kB metabolic pathway is one of the transcriptional hallmarks of aging, and moderate expression of an NF-kB inhibitor in the aging skin of transgenic mice causes rejuvenation of the phenotype of this tissue, as well as restoration of transcriptional features characteristic of young age (Adler et al., 2007). Similarly, in mice of different lines with accelerated aging, genetic and pharmacological inhibition of NF-kB signalling prevents the development of age-associated features (Osorio et al., 2012; Tilstra et al., 2012). A new link between inflammation and aging has emerged following the recent discovery of activation in response to inflammation and stress of NF-kB in the hypothalamus and triggering a signalling metabolic pathway leading to reduced gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) production by neurons (Zhang et al., 2013). Reduced GnRH may contribute to numerous age-related changes such as brittle bones, muscle weakness, skin atrophy and reduced neurogenesis. Consequently, GnRH administration prevents age-related impairment of neurogenesis and slows aging in mice (Zhang et al., 2013). These observations suggest that the hypothalamus, through GnRH-mediated neuroendocrine effects, may modulate systemic aging by integrating triggered NF-kB inflammatory responses.

Further evidence for a link between inflammation and aging in vivo was found by work on the mRNA decay factor AUF1, which is involved in terminating the inflammatory response through cytokine-mediated mRNA degradation (Pont et al., 2012). AUF1-deficient mice have a marked cell senescence and premature senescence phenotype that can be restored by expression of this RNA-binding factor. Interestingly, in addition to regulating mRNA decay involving inflammatory cytokines, AUF1 plays a role in telomere length maintenance by activating the expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase TERT (Pont et al., 2012), again demonstrating that a single factor can influence different key features of aging.

A similar situation occurs with sirtuins, which also influence the aging-associated inflammatory response. Several studies have shown that by deacetylating histones and components of inflammatory signalling pathways such as NF-kB, SIRT1, it is possible to reduce the expression of inflammation-related genes (Xie et al., 2013). Consistent with these findings, reduced SIRT1 levels correlate with the development and progression of many inflammatory diseases, and pharmacological activation of SIRT1 in mice can prevent the development of inflammatory responses (Gillum et al., 2011; Yao et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2010). SIRT2 and SIRT6 can also prevent the development of inflammatory response by deacetylation of NF-kB subunits and transcriptional repression of their target genes (Kawahara et al., 2009; Rothgiesser et al., 2010).

Other types of intercellular communication

Evidence is accumulating that age-dependent changes in one tissue can lead to age-specific abnormalities in other tissues, explaining the inter-organ coordination of the aging phenotype. In addition to inflammatory cytokines, there are other examples of ‘contagious senescence’ or the ‘bystander’ effect, in which senescent cells induce senescence in neighbouring cells through intercellular gap junctions and intercellular processes, involving AFC (Nelson et al., 2012). The microenvironment contributes to the development of age-dependent functional defects in CD4+ T cells, which has been investigated in a mouse model with adaptive transfer (Lefebvre et al., 2012). Lifespan-increasing manipulations targeting only one tissue may slow down the aging process in other tissues as well (Durieux et al., 2011; Lavasani et al., 2012; Toma´ s-Loba et al., 2008).

Repair defective intercellular communication

There are several ways to restore defective intercellular communication, also responsible for aging, which include genetic, nutritional and pharmacological interferences that can improve the decreasing efficiency of intercellular interactions with age (Freije and Lo´ pez-Otı´n, 2012; Rando and Chang, 2012). Of particular interest are OP techniques to increase longevity (Piper et al., 2011; Sanchez-Roman et al., 2012) and rejuvenation strategies based on the use of systemic blood factors identified in parabiosis experiments (Conboy et al., 2005; Loffredo et al., 2013; Villeda et al., 2011). Moreover, short-term administration of anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin can increase longevity in mice and promote healthy aging in humans (Rothwell et al., 2011; Strong et al., 2008). Given that the intestinal microbiome influences the functioning of the host immune system and has systemic metabolic effects, it can be inferred that it is possible to increase longevity by manipulating the composition and functionality of the complex and dynamic intestinal bacterial ecosystem of the human body (Claesson et al., 2012; Ottaviani et al., 2011).

In summary

There is strong evidence that ageing affects not only cells, but also affects general changes in intercellular communication, which provides an opportunity to control ageing at this level. Evidence for this is rejuvenation through systemic blood factors (Conboy et al., 2005; Loffredo et al., 2013; Villeda et al., 2011).

Conclusions and perspectives

All nine key attributes of ageing listed in this review can be divided into three groups: core attributes, antagonistic attributes and integrative attributes (Figure 6). The common characteristic of the core signs is that they are unambiguously negative. They are DNA damage, including chromosomal aneuploidies; mitochondrial DNA mutations; telomere shortening, epigenetic shift and defective proteostasis. In contrast to the major traits, antagonistic ones cause different effects depending on the intensity of manifestation. In small amounts they have favourable effects, but in large amounts they become deleterious. These include senescence, which protects the body against cancer, but which in excess accelerates aging. Similarly, AFCs mediate cell signalling and survival, but when exceeding a concentration threshold for prolonged periods of time can cause cellular damage; likewise, optimal nutrient recognition and optimal anabolism are indisputably essential for survival, but their prolonged presence in a state of high activity can develop into pathology. These key traits can be seen as the body’s defence against damage or nutrient deficiency. But when they are in a state of chronic activity, they no longer fulfil their function but provoke further damage. The third category includes integrative features – stem cell depletion and impaired intercellular communication – that directly affect cellular homeostasis and function. Despite the interconnectivity between all key features, we propose a definite hierarchy (Figure 6). Key traits can be triggers whose negative effects accumulate over time. Antagonistic traits that are beneficial in principle become detrimental under the influence of core traits. Finally, integrative traits manifest themselves when the accumulated damage caused by key and antagonistic traits cannot be compensated for by mechanisms of tissue homeostasis. Since key traits manifest together and are closely related in aging, understanding the causal relationship between them is an important issue for further research.

Figure 7: Measures that may contribute to human life extension. Source: Cell Magazine

All nine hallmarks of aging are depicted, along with possible therapeutic strategies that have been experimentally validated in mice.