New functions of gut microflora

“We are what we eat.” That’s what Hippocrates said. But could he have imagined how right he was? Judging by the latest scientific data, the food consumed has a very strong effect on our gut microflora, which ultimately affects our body. Moreover, it has quite a tangible effect — for example, by changing our weight! It turns out to be a vicious circle: human — microflora — human.

The role of intestinal microflora in the regulation of many body processes has long been known. For example, it forms a protective barrier of the intestinal mucosa, stimulates the immune system [1], neutralizes toxins, produces vitamins, digests fiber, and much more. But science, as you know, does not stand still, and new data is emerging. For example, the relationship between the state of the intestinal microflora and obesity, as well as the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), is now being considered!

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

What is normoflora and what are its functions?

Let’s remind you what the normal human microflora is. Normoflora (microflora in a normal state, or eubiosis) It is a set of microbial populations of individual organs and systems characterized by a certain qualitative and quantitative composition and maintaining the biochemical and immunological balance necessary to preserve human health.

The intestinal microbiome, referred to by some authors as a separate organ, is responsible for metabolic processes in the body (Fig. 1). Bacteria inactivate enzymes, hormones, toxins, decompose bile acids, neutralize allergens, form lactic acid, which helps digestion, promote the absorption of vitamins D and B12, calcium and iron in the intestine, and vitamins B1, B2, B6, B12, H, K, C, nicotinic, pantothenic and folic acids are also synthesized [2]. Microflora determines to a large extent not only the physical component of human life, but also the mental one. It has been found that bacterial waste products can directly affect the brain. For example, at least two types of intestinal bacteria produce gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [3] is a neurotransmitter responsible for the timely quenching of arousal processes in the central nervous system, and possibly helping to maintain normal sleep and absorb glucose [4]. And recent scientific developments relate the composition of the intestinal microbiota to the manifestation of autism and depression.

Picture 1. The main functions of normal microflora. [2]

The metabolic activity of the intestinal microbiota, in addition to satisfying the bacteria’s own needs, helps to extract calories from the food consumed by the host, helps to store this energy in its fat depots, that is, to form adipose tissue. In experiments with gnotobiotic (antimicrobial) mice populated with certain bacteria, it was shown that the intestinal microflora ensures the decomposition of food polysaccharides that are indigestible by the host into digestible forms — but this is hardly news. The finding was that this process was accompanied by increased absorption of monosaccharides from the intestine and their entry into the portal vein, possibly due to an increase in the density of the capillary network in the mucous membrane of the small intestine under the influence of the microbiota. This led to increased hepatic lipogenesis, that is, the synthesis of fatty acids from carbohydrates. The fact is that liver cells respond to an increase in blood glucose and insulin levels by expressing the genes of the transcription factors ChREBP and SREBP-1, which activate genes for the biosynthesis of triglycerides, that is, fats. Increased production of these transcription factors was observed after colonization of mouse intestines with microbiota. In addition, intestinal bacteria helped to place newly produced triglycerides in fat cells (adipocytes), interfering with the work of host genes: the microflora increased the activity of lipoprotein lipase necessary for this, suppressing the synthesis of its inhibitor in the epithelium of the small intestine.

However, it is worth recalling here that we were talking about mice, about a specific enterotype of their microflora (a biocenosis dominated by certain groups of bacteria) and, in general, about the basic functions of the microbiota. Therefore, based on this work, it is not necessary to draw a conclusion about the harmful effects of any intestinal bacteria on the host, it is just how the hypothesis of multiple and interrelated mechanisms of the intestinal microbiota’s influence on the host’s energy metabolism appeared, and with it the hope that correcting this influence will help to cope with the epidemic of obesity [5]. The authors suggested that one individual’s microbial “bioreactor” may be more energy efficient than another’s. And the factors influencing this will be discussed later.

The microflora of people with normal weight and obese differs

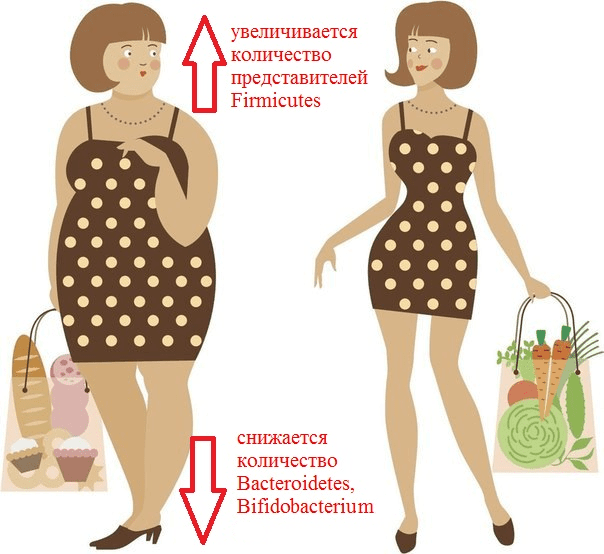

Recent experiments have shown that changes in the microflora relate to the causes of obesity, not to its consequences. If the intestines of gnotobiotic mice are populated with the microbiota of obese mice, the animals will gain weight faster than in the case of bacterial transplantation from lean mice. Moreover, according to the composition of the microbiota, it is possible to predict with 90% probability whether a person has obesity [6]. Just imagine! Now imagine that by changing the composition of a person’s intestinal microflora, it will be possible to regulate his weight (Pic. 2).

Picture 2. What is remarkable about the composition of the intestinal microflora of an obese person?

It has been repeatedly revealed that obesity increases the number of representatives of the Firmicutes type (for example, Clostridium coccoides, C. leptum) and the Enterobacteriaceae family (Esherichia coli). At the same time, the number of representatives of the Bacteroidetes type (Bacteroides, Prevotella) is decreasing, and populations of bacteria of the genera Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are decreasing [7]. It has previously been shown that a high-fat diet promotes inflammation of the intestinal mucosa, mediated by a decrease in the number of lactobacilli. This inflammation predisposes to the development of obesity and insulin resistance, that is, type 2 diabetes. In 2016, experiments with mice were able to establish a link between these conditions and a deficiency of specific strains. Lactobacillus reuteri in Peyer’s patches. The fact is that fat-rich foods ensure the selection of bacterial strains that are resistant to oxidative stress. And these turned out to be lactobacilli, which secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines. Conversely, the “good” strains of L. reuteri, producers of anti—inflammatory substances, were displaced from the population [8].

As already mentioned, the analysis of the intestinal microbiome revealed a sharp decrease in the proportion of Bacteroidetes and an increase in the proportion of Firmicutes in mice with hereditary obesity compared to normal mice [9]. The same changes were often observed in humans: in one study, 12 obese patients differed from the lean control group by having a reduced bacterial content Bacteroidetes and elevated Firmicutes. Then the patients were transferred to a low-calorie diet (a diet with a restriction of fats and carbohydrates) and changes in the composition of their intestinal microflora were monitored for a year. It turned out that the diet significantly reduced the number of Firmicutes and increased the proportion of Bacteroidetes, but most importantly, these changes correlated with the degree of weight loss [9]. Nevertheless, the relationship of body mass index with the proportion of Bacteroidetes/ Firmicutes has not yet been proven [10].

Metabolic changes

124 Europeans were examined as part of the MetaHIT project dedicated to the study of the intestinal metagenome, that is, the totality of the genomes of all intestinal inhabitants [11]. The total number of genes in the intestinal microbiome was 150 times (!) higher than the number of human genes. But it is worth noting that an excess of fatty foods led to a reduction in bacterial diversity.: obese people had an average of six fewer types of bacteria than those with normal body weight. The results of the metagenomic analysis divided the participants of the experiment into two groups: carriers of the “small genome” (low gene count) and carriers of the “large genome” (high gene count). A small genome is a metagenome with relatively few genes from different bacterial species: the difference between the “small” and “large” genomes in terms of the number of genes reached an average of 40%. In most individuals with a poor intestinal metagenome, Bacteroides prevailed, while in those with a rich intestinal metagenome, Methanobrevibacter prevailed. At the same time, the two described categories of people differed greatly in the representation in their microbiota of groups forming a pro-inflammatory (Bacteroides, Ruminococcus gnavus) or anti-inflammatory (Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia inulinivorans) background. The former were much more often found in individuals with poor metagenome.

The results of the MetaHIT project clearly indicate that the abundance of human intestinal microflora correlates with its metabolic markers, while bacterial genes play almost a greater role in the pathogenesis of obesity than our own.

Among the owners of the “small genome” (23% of all participants), there were more overweight people. This group as a whole was characterized by disturbances in the tissue response to the action of insulin, which led to an increase in its concentration in the blood. Such people also showed a statistically significant decrease in the content of the so—called “good cholesterol” – high-density lipoproteins that transport cholesterol from various tissues to the liver for further transformation and utilization. There was also a tendency to increase blood levels of triglycerides, free fatty acids and the hormone leptin, high concentrations of which are considered as an independent risk factor for the development of cardiovascular pathologies and thrombosis. (The main risk factors also include specific variants of the lipid profile, high blood pressure, chronic inflammatory background and smoking.)

A number of studies have shown that in humans, whose diet is dominated by plant components, the microbiome is dominated by bacteria that break down polysaccharides, and these are representatives of the Bacteroidetes type, some of which protect the host from the development of local and systemic inflammation. At the same time, the number of firmicutes and enterobacteria, which are often referred to as “pathobionts,” is decreasing among plant-based food lovers: they are able to create an inflammatory environment due to the lipopolysaccharide of their outer membrane and increased permeability of the intestinal epithelium, which leads to large-scale penetration of lipopolysaccharide molecules into the bloodstream and provocation of metabolic endotoxemia, and possibly cravings for regular overeating. By the way, this is exactly how events develop against the background of a high-fat diet. On the contrary, most studies associate a vegetarian diet with a reduced risk of developing metabolic syndrome and related “diseases of civilization” [7].

The active decomposition of plant fiber by the corresponding bacteria of the large intestine leads to the formation of monosaccharides and short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). The latter, especially butyric acid, are necessary not only for the intestinal microflora, but also for the macroorganism. For example, they lower the pH of the intestinal contents, thereby displacing a number of pathobionts from the community, and most importantly, they provide enterocytes with energy and protect them from oncotransformation and inhibit inflammatory signaling pathways. But even here, not everything is so clear: on the one hand, an excess of SCFA can enhance lipogenesis and therefore contribute to the development of obesity, on the other hand, some studies have shown a beneficial effect of SCFA on the lipid profile and blood glucose levels. This positive effect may be mediated by the binding of FGF to G-protein—coupled cellular receptors, GPR41 and GPR43, which leads to hormonal changes leading to a feeling of satiety and increased tissue sensitivity to insulin. In general, the effects of the production of large amounts of FGM by the microflora are influenced by a variety of factors, from the type and quantity of food “raw materials” to variations in the bacterial composition inherent in the early stages of the body’s development. On the other hand, dietary fiber prevents metabolic disorders regardless of the composition of the microflora. Moreover, the preventive effect of a predominantly plant-based diet on the development of atherosclerosis has been shown by studies related to the biotransformation of L-carnitine: it is certain intestinal bacteria, which are quite useful from other points of view, that convert the L-carnitine contained in red meat into atherogenic substances [7], [12].

Another competitive article tells a fascinating story about the colonization of the human body by bacteria and the leading role of colonizers in the formation of “correct” immune responses of the host: “The gut microbiome: the world inside us” [13]. — Ed.

Intestinal bacteria are able to reduce the level of triglycerides in the blood, improve glucose and lipid metabolism also due to their direct participation in the circulation of bile acids, and reduce fat reserves by activating the already mentioned lipoprotein lipase inhibitor [10]. But it’s still difficult to draw any conclusions: sometimes the experimental results are too contradictory. A new review will help to get an idea of the contradictions and their causes, and most importantly, about possible mechanisms linking the activity of the microbiota with the host’s metabolism [10].

The role of microflora in the development of type 1 and type 2 diabetes

Treatment and prevention of type 2 diabetes are closely related to weight normalization. And it requires a change in the nature of nutrition (the ratio of macro- and micronutrients) in combination with an increase in physical activity: that is, it is important to create conditions for some energy deficit, when more calories are spent than are received [14]. Although the role of intestinal microbiocenosis in the regulation of energy metabolism is not fully understood, it is already clear that exposure to the microflora can definitely help eliminate obesity and compensate for type 2 diabetes.

And, oddly enough, such an impact can reverse the alarming situation with a disease that is fundamentally pathogenetically different — type 1 diabetes. It is an autoimmune disease associated with the aggression of T-lymphocytes against beta cells of the pancreas, which produce insulin. If in the case of type 2 diabetes, an increase in blood glucose levels occurs due to the insensitivity of tissues to insulin (which prevents cells from absorbing glucose), then in type 1 diabetes there is simply not enough insulin itself. The development of this disease requires a combination of a number of circumstances — genetic and environmental, and among the latter, as it turned out, the restructuring of the intestinal microbiome plays a huge role. The intestinal normoflora immediately after colonization trains the host’s immune system so that it distinguishes between its own and others, reacts violently to strangers, but stops in time [13]. Apparently, with type 1 diabetes, something in this chain breaks down.

In one experiment with rats predisposed to type 1 diabetes, differences in the composition of the intestinal microflora were revealed in animals with and without diabetes [15]. The latter were found to have a lower content, oddly enough, of representatives of the Bacteroidetes type, which, in a number of studies, rather protected against metabolic disorders. But as we know, the effects of bacteria vary radically not only from type to type, but even from strain to strain… The use of antibiotics in these rats prevented the development of diabetes. The researchers suggested that changes in the intestinal microflora caused by taking antibiotics lead to a decrease in the overall antigenic load and subsequent inflammation, which may contribute to the destruction of beta cells of the pancreas. However, as usual, in a number of other experiments with animals and humans, the effect of antibiotics (which, of course, differed) it was the opposite [16].

In human children with type 1 diabetes and healthy controls, a significant difference in the composition of the intestinal microbiota was revealed, and in diabetics, the ratio was increased Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes and bacteria that utilize lactic acid predominated. Healthy children had more butyric acid producers. In general, it is believed that certain deviations in the composition of the microflora occur mainly during critical periods of ontogenesis (during embryogenesis, birth, breastfeeding and puberty) They contribute to the strengthening of pro-inflammatory signaling with all the resulting immune consequences [16]. It is possible that due to concomitant disruption of the barrier function of the intestinal epithelium, bacterial antigens entering the bloodstream and penetrating the pancreatic lymph nodes interact with NOD2 receptors and provoke T cells to attack pancreatic beta cells [17].

Thus, the data obtained so far form the basis for further study of the role of intestinal microflora in the mechanisms of development of obesity and type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and also indicate the possibility of preventing and treating these pathologies in new ways – by correcting our microbiome.

Literature

- Immunostimulating filament bacteria: they are finally tamed!;

- Microflora of the gastrointestinal tract. Propionics website;

- Oleskin A.V. (2009). Neurochemistry, symbiotic microflora and nutrition (biopolitical approach). Gastroenterology of St. Petersburg. 1, 8–16;

- Calm as GABA;

- Dibaise Bäckhed F., Ding H., Wang T., Hooper L.V., Koh G.Y., Nagy A. et al. (2004). The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101 (44), 15718–15723;

- The zoo in my stomach;

- Glick-Bauer M. and Yeh M.-C. (2014). The Health advantage of a vegan diet: exploring the gut microbiota connection. Nutrients. 6 (11), 4822–4838;

- Sun J., Qiao Y., Qi C., Jiang W., Xiao H., Shi Y., Le G.W. (2016). High-fat-diet-induced obesity is associated with decreased antiinflammatory Lactobacillus reuteri sensitive to oxidative stress in mouse Peyer’s patches. Nutrition. 32 (2), 265–272;

- Ley R.E., Bдckhed F., Turnbaugh P.J., Lozupone C.A., Knight R.D., Gordon J.I. (2005). Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 11070–11075;

- Khan M.J., Gerasimidis K., Edwards C.A., Shaikh M.G. (2016). Role of gut microbiota in the aetiology of obesity: proposed mechanisms and review of the literature. J. Obes. 2016, 7353642;

- Final Report Summary — METAHIT (Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract). Website of the European Commission CORDIS (Community Research and Development Information Service);

- Koeth R.A., Levison B.S., Culley M.K., Buffa J.A., Wang Z., Gregory J.C. et al. (2014). γ-Butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metab. 20 (5), 799–812;

- Микробиом кишечника: мир внутри нас;

- Korner J. and Leibel R.I. (2003). To eat or not to eat — how the gut talks to the brain. N. Engl. J. Med.349, 926–928;

- Brugman S., Klatter F.A., Visser J.T., Wildeboer-Veloo A.C., Harmsen H.J., Rozing J., Bos N.A. (2006). Antibiotic treatment partially protects against type 1 diabetes in the bio-breeding diabetes-prone rat: is the gut flora involved in the development of type 1 diabetes? Diabetologia. 49, 2105–2108;

- Paun A., Yau C., Danska J.S. (2016). Immune recognition and response to the intestinal microbiome in type 1 diabetes. J. Autoimmun. 71, 10–18;

- Costa F.R., Françozo M.C., de Oliveira G.G., Ignacio A., Castoldi A., Zamboni D.S. et al. (2016). Gut microbiota translocation to the pancreatic lymph nodes triggers NOD2 activation and contributes to T1D onset. J. Exp. Med. 213 (7), 1223–1239.

Published

Июль, 2024

Duration of reading

About 5-6 minutes

Category

Genetics

Share