Nutrigenomics: nutrition vs. disease

More and more people in the world are dying from chronic non-communicable diseases (diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular diseases). What can stop this epidemic? The answer will come from nutrigenomics, a new field of science that studies how food affects gene expression. The article will reveal the molecular mechanisms of how food affects genes; tell you which foods you should eat more often and which ones you should avoid in order to live longer and healthier; and describe the prospects for nutrigenomics in the future.

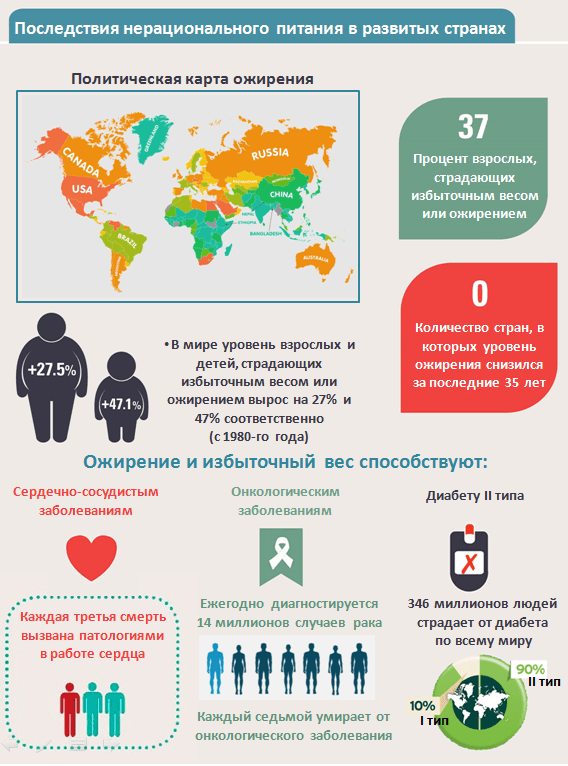

Since the time of Ancient Greece, it has been known that food influences the state of body and mind and can cure diseases. However, fundamental discoveries in the science of nutrition were made only in the 18th and 20th centuries: the chemical composition of food and the main pathways of metabolism were studied. Until the middle of the 20th century, due to unbalanced diets, ailments related to vitamin and mineral deficiencies were common, so their functions were studied especially actively. Today, however, developed countries are faced with other consequences of unbalanced diets – obesity and type II diabetes (Figure 1). Moreover, it has been discovered that life expectancy and the development of the “killer trio” – cardiovascular, neurodegenerative and cancerous diseases – depend on a person’s diet. It became obvious to doctors and scientists that for effective treatment and prevention of the above-mentioned diseases it is necessary to understand the mechanisms of food impact on the body at the cellular and molecular levels. At the beginning of the 21st century, international genomic projects were completed, providing a wealth of genetic information for analysis, and productive molecular techniques were developed to investigate the “inner life” of the cell. All these factors led to the birth of a new science – nutrigenomics.

Nutrigenomics investigates the effects of various food components and supplements on gene expression. It is expected that determining the biochemical pathways of food and gene interactions will make it possible to effectively treat non-communicable diseases (e.g. diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases) and prevent their development by identifying early markers of metabolic disorders and creating an individualised nutritional plan.

So how does food regulate gene function?

Picture 1: Consequences of unbalanced diets in developed countries: prevalence of obesity and type II diabetes. Overweight and “Western” type of nutrition (abundance of fried food, red meat, sweet carbonated drinks, fatty dairy products) contribute to the development of cardiovascular diseases, cancer and type II diabetes.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Nutrigenomics: from food to genes

Gene expression is the process by which hereditary information from a gene is converted into a functional product – RNA or protein. Gene expression is regulated at different stages, but the main “checkpoint” is the initiation of transcription (synthesis of RNA on the DNA matrix). The initiation of transcription depends both on the availability of necessary proteins (transcription factors, enzymes, etc.) and on the availability (affinity) of DNA for these proteins (i.e. epigenetic modifications). Food components can influence both processes.

Epigenetic modifications

All cells in our body – from neurons to white blood cells – carry the same genetic material. But each cell expresses a specific set of genes – this determines the specialisation of cells. Switching genes on/off is regulated by epigenetic modifications (such modifications do not affect the DNA sequence, but change its “packaging”). In the cell, DNA is compacted, i.e. wound on “beads” – a complex of histone proteins, various chemical modifications of which switch a gene on or off. In addition, gene switching off occurs when the DNA molecule itself is modified (methylation).

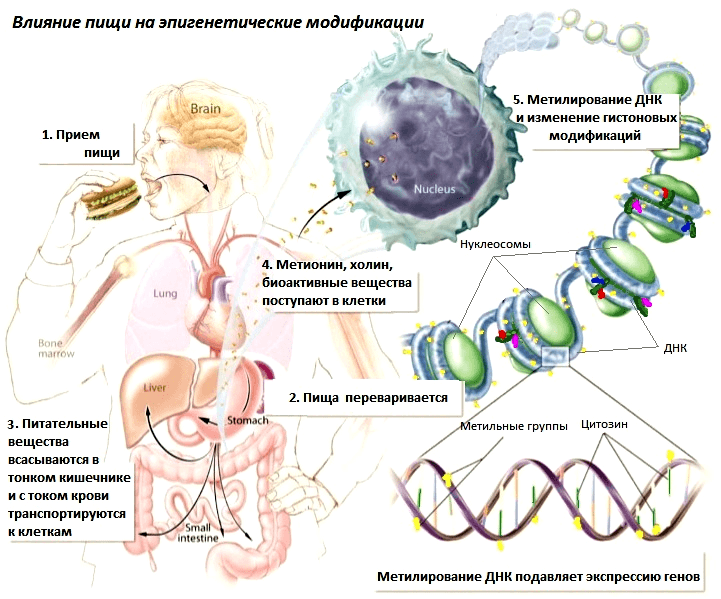

Some food components influence these processes (Picture 2):

- Histone acetylation (gene switching). Sulforaphane (found in cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower) and diallyldisulfide (from garlic) – switch on genes by inhibiting enzymes that repress the gene by removing the acetyl tag from histones. Sulforaphane is therefore able to switch on genes silenced in cancer cells – regulators of normal division, which suppresses tumour growth. Uric acid, which is produced by the human microflora when fibre is consumed, has a similar effect on gene function and also activates the immune system, which suppresses cancer cell growth. The inhibitory effect of butyric acid on metastasis was shown in rats on a model of rectal cancer [8].

- DNA methylation (gene silencing). Sources of methyl groups (choline, methionine, folic acid) are found in eggs, spinach, legumes and liver. In adult rats, chronic deficiency of methyl groups leads to spontaneous tumour formation [9], and also leads to activation of mobile genome elements [10]. The experiment conducted by Jirtle and Waterland with transgenic agouti rodents (Avy agouti), which have yellow colouring and predisposition to obesity, diabetes and cancer, is widely known. When choline, methionine and folic acid were added to the feed of pregnant agouti females, they gave birth to normal offspring with brown coat colour and no health abnormalities [11]. The fact is that the presence of methyl group sources in the maternal diet promoted methylation (and, consequently, switching off) of the agouti gene, which caused a morbid phenotype in embryos.

- Sources of methyl groups, in particular folic acid, are necessary for normal foetal development and pregnancy in women. Its deficiency increases the risk of preterm labour, miscarriage, abnormalities in the fetal nervous system and low birth weight [14]. The exact mechanisms of folic acid action are still unclear; it is only known that it increases methylation of the IGF2 (insulin-like growth factor 2) gene, which is involved in fetal growth and development [15].

Picture 2: Mechanism of the effect of food on epigenetic modifications.

Transcription factors

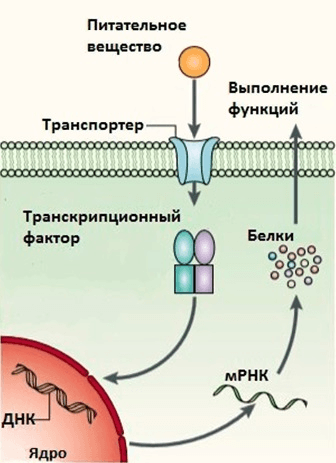

Picture 3: Mechanism of action of nutrients on gene expression through transcription factors.

The second mechanism by which food changes gene expression is illustrated by the following scheme: “food component → receptor → signalling pathway → transcription factor → gene activation” (Pic. 3). Receptors recognise a strictly defined structure of substances, so similar food components have different effects on the organism (e.g. saturated and unsaturated fats). In this scheme slight variations are possible, for example, nuclear receptors combine the functions of a receptor and a transcription factor: they recognise various hydrophobic components of food or their derivatives (fatty acids, vitamin D, retinoic acid, bile salts, etc.) and then change the activity of genes regulated by them.

Food consists of proteins, carbohydrates and fats. Food components are broken down during digestion into simpler substances (amino acids, monosaccharides, fatty acids), which are then transported into cells and bound by receptors. The signal from the receptor spreads through the cell, reaches the nucleus and gene expression is altered. Prolonged changes in gene expression ultimately affect health and longevity. But more on that in a moment.

Proteins in the digestive tract are broken down to amino acids, which are then transported inside cells. Floating in the cell cytoplasm is the molecule mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), which is activated by high concentrations of amino acids and regulates numerous aspects of metabolism in the cell. Notably, the mTOR signalling pathway is a conserved biochemical pathway that regulates aging in animals. Genetic mutations that attenuate mTOR pathway signalling prolong the lifespan of worms, flies and mice . Since mTOR is activated by amino acids, a protein-restricted diet would be expected to favour health and longevity. Indeed, consumption of low amounts of protein or methionine (an essential amino acid) increased longevity in model animals. In humans, a diet low in protein to carbohydrate ratio reduces the risk of cancer, obesity and neurodegenerative diseases. According to studies, elderly people (50-65 years old) who get more than 20% of their daily calories from protein are four times (!) more likely (!) to die of cancer, and their overall mortality rate is 75% higher compared to people on a low-protein diet (i.e., less than 10% of daily calories). Interestingly, no correlation was found between plant protein intake and mortality rates. This is thought to be due to the amino acid composition of plant proteins, which contain less methionine and cysteine.

Carbohydrates are broken down into monosaccharides during digestion; the best known member of this class is glucose. An increase in blood glucose levels triggers the production of the hormone insulin. Insulin is captured by receptors on the surface of cells, which leads to the activation of the IIS (Insulin/Insulin-like growth factor Signalling) signalling pathway, which triggers glucose uptake by cells and stimulates cell growth and division. The IIS signalling pathway is closely intertwined with the mTOR pathway, and accordingly, its level of activation has implications for health and longevity. Mice heterozygous for the IGF-1 (Insulin-like growth factor) receptor (Igf1r+/-) lived on average 26% longer than their homozygous brothers (Igf1r+/+). As for humans, genetic polymorphisms that reduce IIS pathway signalling are associated with longevity. Numerous studies demonstrate that caloric restriction in animals reduces IGF levels in the blood; along with IGF, the risk of atherosclerosis, cancer, and other diseases falls. In humans, fasting a few days a week (consuming less than 25% of daily calories) improves markers of cardiovascular disease such as blood cholesterol (LDL) levels and insulin sensitivity.

Fats are processed to fatty acids, monoglycerides and glycerol. The biochemical effects of fatty acids are being actively investigated in nutrigenomics, as they trigger many signalling pathways and many diseases are associated with impaired lipid metabolism. Fatty acids can be divided into two main classes: unsaturated (which include polyunsaturated fatty acids and trans fats) and saturated.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). PUFAs are found in olive oil, seeds, tuna and salmon. PUFAs are essential for the normal functioning of the body, their use has a beneficial effect on the cardiovascular and nervous systems. Inside the cell, PUFAs are recognised by nuclear PPAR receptors (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors), which also act as transcription factors and regulate metabolic genes. Activation of PPARα in the liver promotes catabolism of body fat (i.e., fat utilisation). PUFAs also reduce the expression of genes involved in the synthesis of cholesterol and fatty acids. Omega-3-fatty acids, which are rich in fish oil, flaxseed oil and walnuts, are particularly beneficial for the body. Fish oil lowers cholesterol levels in the blood and liver. Studies demonstrate that ω-3-fatty acids (but not ω-6-fatty acids) inhibit the growth of colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo. In addition, ω-3-fatty acids have anti-inflammatory effects because they function as substrates for the synthesis of the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin E3, protectins and resolvins involved in inflammation resorption and cellular defence. In addition, ω-3-fatty acids alter histone acetylation and thus inhibit the action of the transcription factor NF-kB on the immune response and apoptosis genes it regulates.

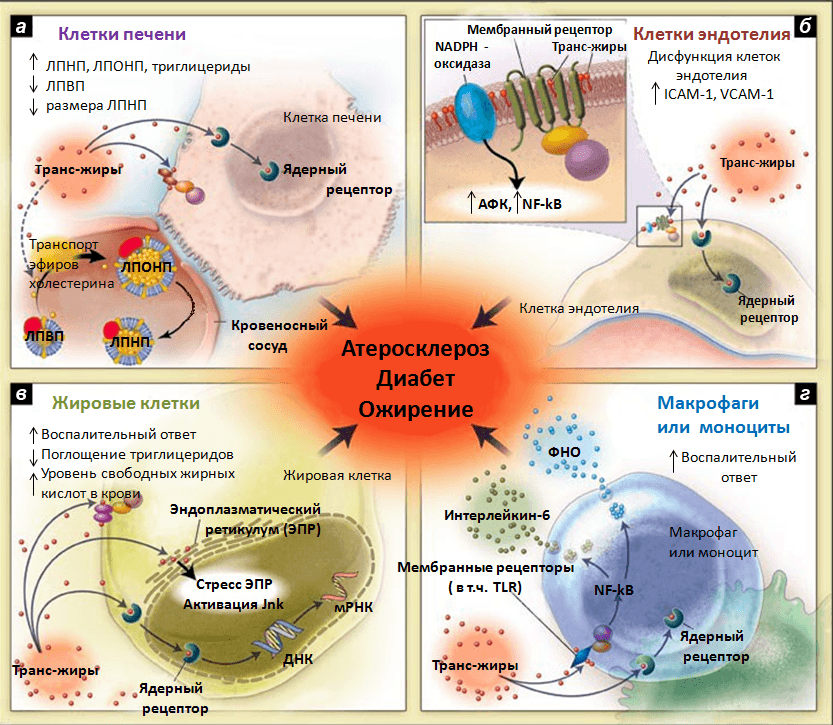

Trans fats. Trans fats are formed in the food industry from unsaturated fatty acids in the production of margarine, which is used in the manufacture of baked goods, crackers, chips, etc. Studies demonstrate that there is a direct correlation between the consumption of trans fats and the development of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, allergies, breast cancer, and shortened gestation period. In experiments conducted on mice, scientists determined that trans fats increase the expression of PGC-1, a key regulator of lipid metabolism, in the liver. This promotes the excretion of low-density lipoproteins into the blood and the deposition of cholesterol in blood vessels. Also, trans-fats are incorporated into the cell membrane, cause inflammation and disrupt cellular function (Pic. 4).

Picture 4: Putative mechanisms of action of trans-fats. (a) Trans-fats alter production, secretion and catabolism of lipoproteins in liver cells, and affect the transport of cholesterol esters to very low density lipoproteins. (b) In endotheliocytes, synthesis of circulating adhesion molecules is increased and NO synthase function is decreased. (c)Under the influence of trans fats, normal fat metabolism in adipocytes is altered and the inflammatory response is enhanced. (d)Production of inflammatory mediators (interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor) increases in macrophages. The above effects of trans fats have been confirmed by human studies and contribute to atherosclerosis, diabetes, plaque detachment, sudden death from cardiac abnormalities. The intracellular mechanisms of action of trans fats are not precisely established. Possible: changes in the membrane phospholipids of the cell, which affects the function of membrane receptors (such as NO synthase on endotheliocytes or TLRs on macrophages); direct interaction of trans fatty acids with nuclear receptors that regulate gene transcription (e.g., liver X receptor); mediated or direct effect on EPR, activation of Jnk kinase, which is normally activated in response to cellular stress and regulates apoptosis, cell division, and cytokine production. The putative mechanisms need further investigation.

Saturated fatty acids (SFAs). The main sources of saturated fatty acids are butter, cheese, meat, yolks, coconut oil, palm kernel oil and cocoa butter. There is evidence that SFAs promote inflammation through direct activation of TLR4 (Toll-like receptor) receptors on macrophages [32]. The TLR4 receptor is an innate immunity receptor that recognises a specific component of the bacterial cell wall, which includes a lipid. The signal from TLR4 activates the key transcription factor of the immune response – NFkB. Although the results of studies on the adverse health effects of fatty acids are contradictory, the World Health Organisation recommends reducing the proportion of saturated fatty acids in the diet to 5-10% (of total calories).

It is known that the same factors (identical diet and degree of physical activity) can affect people’s metabolism in different ways. For example, it has recently been found that in women, depending on allele type, PUFA intake can have opposite effects on high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels in the blood. Accordingly, individual genetic variation should be taken into account when conducting nutrigenomic studies.

Nutrigenetics: from genes to food

Nutrigenetics studies how variations in genes are reflected in the digestion and metabolism of food and therefore identifies genetic predispositions to disease. Genetic diseases are divided into monogenic (determined by variation in a single gene) and polygenic (determined by a combination of genes + environmental factors).

Monogenic diseases include, for example, phenylketonuria, gluten disease and lactose intolerance. The cause of such diseases is clear, so the external manifestations are easy to prevent: it is enough to exclude from the diet an indigestible component of food. To prevent polygenic diseases – obesity, type II diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular system disorders – it is necessary to control not only the diet, but also to monitor the degree of physical activity, stress level, etc., as well as the dietary intake. However, accumulating knowledge from nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics allows us to identify risk groups individually (depending on genotype) and determine which foods a given person should avoid and which, on the contrary, should be added to the daily menu in order to minimise the risks of diseases.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD). The development of CVDs is extremely complex, so scientists are still far from establishing all risk factors and ways to eliminate them. However, variations in lipid metabolism genes (apolipoprotein E, A1, A2, A54 genes; PPARs; lipoxygenase-5, etc.) have been identified in the genes of lipid metabolism, the owners of which are more likely to develop CVD from high-calorie diets. It has also been shown that people with a slow metabolism of caffeine have an increased risk of cardiac attacks from its consumption. At the same time, the main risk of CVD development is proved to be the presence of metabolic syndrome, which is characterised by the “deadly four”: increased blood pressure, blood sugar and lipid levels, and obesity. Therefore, the main urgent task in this field is to establish the molecular mechanisms of the common pathological process that leads to such different metabolic disorders.

Cancer. Features of nutrient transport and metabolism contribute to the development (or prevention) of cancer. For example, there is a common mutation that reduces the efficiency of an enzyme required for DNA methylation. When dietary sources of methyl groups (folate and choline) are deficient, carriers of this mutation have an increased likelihood of colorectal cancer. For such people, alcohol consumption is an additional aggravating factor, as alcohol reduces the absorption of folate and increases its excretion from the body. Red meat consumption significantly increases the risk of developing colorectal cancer in both fast N-acetyltransferase and carriers of a particular combination of polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 gene. It has also been found that the probability of cancer increases with a mutation in the gene of one of the types of glutathione transferases (enzymes involved in detoxification), and the constant intake of toxins into the body (through smoking, etc.) is dangerous for people with such a mutation. On the contrary, eating cabbage and other cruciferous vegetables will be extremely useful, as they contain substances that increase the activity of glutathione transferases.

Obesity. A certain variant of the FTO gene (fat mass- and obesity-associated gene) is associated with obesity and diabetes. Studies have found that children with this FTO variant tend to eat more calorie-dense foods when they have unlimited access to food. The effect of this genetic variant is easily modulated by physical activity and a balanced diet.

Despite possible genetic predispositions to obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, environmental factors have been shown to play a significant role in the development of these pathologies. Therefore, WHO has established basic recommendations for maintaining health: eating a variety of fruits and vegetables throughout the day, reducing the consumption of saturated and trans-fats, cured meats, salty foods, moderate alcohol consumption, active lifestyle, and maintaining a normal weight. Various studies have confirmed an inverse relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and cancer incidence. In addition, the accumulating evidence of the beneficial effects on health and longevity of diets low in animal proteins is already forcing nutritionists to develop a new system of balanced nutrition. However, much work remains to be done to fully understand the mechanisms of influence of food components (as well as their combinations) on the organism and possible variations of such influence among the human population. There are a number of problems that need to be solved in order to obtain reliable information and to implement nutrigenomics/nutrigenetics in everyday life.

Challenges

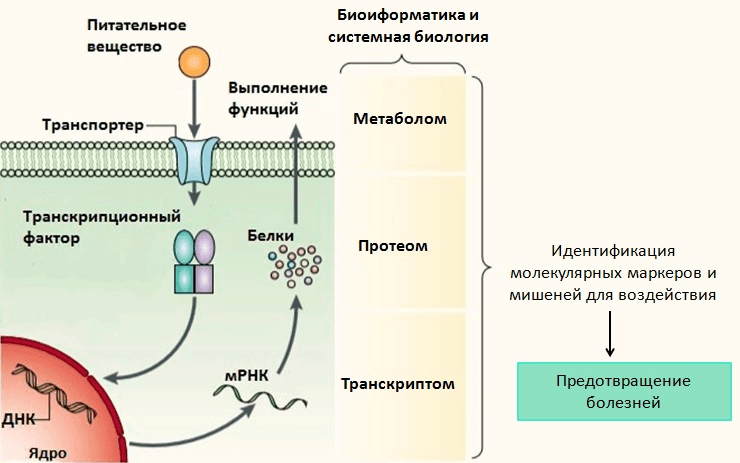

A single meal has a weak effect on the organism, so the duration of nutrient intake is very important in nutrigenomic studies, which complicates the experiments. The following methods are used to analyse changes in gene expression and cell metabolism: epigenetic analysis and analysis of cellular mRNA (transcriptome), proteins (proteome) and metabolites (metabolome) (Figure 5). Unfortunately, to date, methods for obtaining proteome and metabolome are expensive and underdeveloped, and the amount of mRNA is not always proportional to the amount of protein in the cell and does not provide information on protein activity. In addition, studies require quite a large amount of biological material, so blood, in particular, white blood cells (adipose and muscle tissues are in second place) are mainly analysed, but it is still unknown how accurately they reflect early disturbances in metabolism [39].

Picture 5: Nutrigenomic research methods.

Although there is not yet enough reliable information to incorporate nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics into everyday life, there are already companies offering nutrigenetic tests (the US government has issued a report on the dangers and unreliability of such tests). Such companies raise doubts among people about the scientific relevance of fields such as nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics, which hinders their dissemination and implementation in society.

Prospects

Nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics are expected to make a significant contribution to healthcare in the next decade. Establishing the molecular mechanisms of food-gene interactions and identifying early markers of metabolic disorders will enable effective preventive treatment. It is planned to develop individual nutrition plans based on metabolic characteristics and genetic predispositions (Pic. 6). Food products will be tested not only for safety but also for their effectiveness on the body.

Published

July, 2024

Duration of reading

About 3-4 minutes

Category

Nutrition

Share