Why is it so difficult to lose weight or the effect of the gut microbiota on metabolism

At least once in our lives, each of us dreamed of losing weight without strenuous physical exertion and following a strict diet. “Impossible!” you say? “Nothing is impossible,” science will answer. After all, every girl has a slender friend who, without observing the principles of proper nutrition, remains thin. “Good metabolism,” she replies, smiling sweetly. “Good intestinal microflora,” I say. This article will tell you about the relationship between intestinal microflora and waist size. Is it interesting? Then read on!

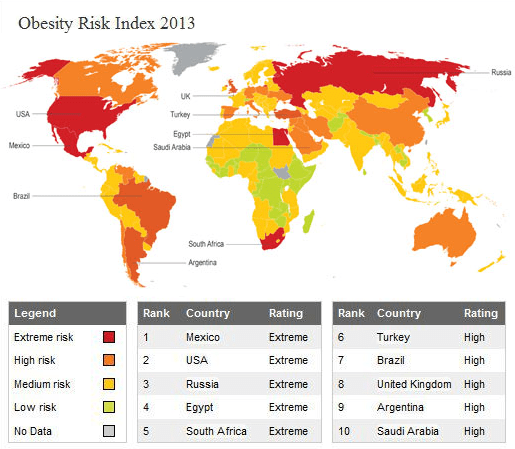

The problem of obesity affects the whole world, as the map in Figure 1 clearly shows. Of course, we cannot remain indifferent to it. So let’s figure out what is the cause of this disease, and is it possible to overcome obesity?

The risk of obesity in the world in 2013

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Is the gut microbiota the key to understanding the causes of the problem?

The intestinal microbiota are microorganisms that live in the gastrointestinal tract in symbiosis with humans. They are divided into beneficial (which help our body by performing a number of vital functions), conditionally pathogenic (which are normally found in the intestine in small quantities, but with a decrease in immunity and an increase in their population can lead to a number of diseases) and pathogenic (which are harmful to human health). Normoflora, or beneficial microflora (bifidobacteria, bacteroids, lactobacilli, fusobacteria, E. coli, enterococci, staphylococci) provides a number of important functions:

- The protective function is performed by forming a protective barrier of the intestinal mucosa. Normoflora (obligate microflora) suppresses or reduces the adhesion of pathogenic agents by competitive exclusion. For example, lactobacilli of the parietal (mucosal) microflora occupy certain receptors on the surface of epithelial cells. Pathogenic bacteria that could bind to the same receptors are eliminated from the intestine due to the fact that they simply have nowhere to attach to. Obligate microflora can also fight off intruders more “aggressively”: for example, bifidobacteria produce lactic acid and acetate due to fermentation of oligo- and polysaccharides, which inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria, which increases the body’s resistance to intestinal infections.

- The microbiota also performs an immunogenic function (by stimulating the immune system, local immunity, including the production of immunoglobulins). For example, enterococci can activate B lymphocytes and increase the synthesis of IgA (which is responsible for local immunity), and E. coli produces colicin B, which inhibits the growth of pathogenic microflora. Lactobacilli act on specific accumulations of lymphoid tissue, thereby stimulating cellular and humoral immune responses.

- These microorganisms are also involved in metabolism, providing membrane digestion, regulating the biotransformation of bile acids by reducing the absorption of cholesterol from the digestive tract. And cholesterol, as you know, is the material for the formation of bile acids in the liver. At the same time, they form an immunological tolerance to food and microbial agents. The normal microflora participates in the synthesis and absorption of B vitamins, folic and nicotinic acids, calcium, iron, and vitamins D and K. In addition, thanks to the enzymes of microorganisms, fiber (for example, cellulose) is digested, which cannot be absorbed without their help. After the anaerobic digestion of fiber, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, methane and volatile fatty acids are formed (most of which are absorbed into the blood and used for energy purposes). Based on this, another important function appears — the production and supply of energy or an energy substrate (butyrate) to the body.

Analyzing these data, we understand how important the gut microbiota makes to our health. As he said George Ratner: “Just think about what clever and complex processes the body continuously conducts in order to keep us healthy, and how stupidly and incompetently we act in life.”

What determines the composition of the intestinal microbiota (CM)?

The quantitative and qualitative composition depends on many factors:

- age (the percentage of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria decreases in the elderly);

- general condition of the body (presence of chronic gastrointestinal diseases);

- taking medications (antibiotics);

- genetic features of the body;

- nutrition.

For example, adherents of the Western diet (with a high fat content) have a decrease in the population. Bacteroidetes and an increase in Firmicutes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota (CM) [1]. Of course, the fact that regular intake of fatty foods leads to obesity is not new, but what role does the intestinal microflora play here? And what happens if part of the intestinal microbiota is transferred from an obese mouse to a sterile (devoid of intestinal microflora) body? And can certain groups of microorganisms lead to obesity? Let’s try to find the answers to all these questions.

Is there a link between obesity and KM composition?

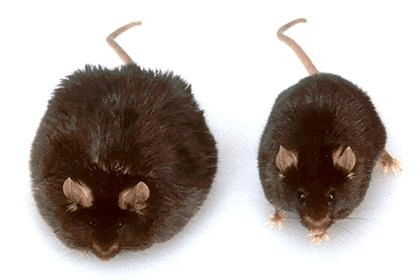

Vanessa Ridaura and her colleagues set up a very interesting experiment [2], [3]. They obtained samples of intestinal microflora from four pairs of human twins (in which one of each pair was thin and the other was obese). These samples were injected into mice grown under sterile conditions (there were no microorganisms in the intestines of these rodents) and the animals were observed gaining weight (pic. 2). The mice were fed a diet rich in fiber and with a normal percentage of fat.

It turned out that those mice that received the microflora of thin people retained a normal percentage of body fat after a few weeks, while those that received the intestinal microflora of fat people began to gain weight (even though they ate low-fat food). When the mice of both groups were placed in the same cage after infection, and they began to exchange microflora (mice sometimes eat feces), the microbiota of the thin ones “defeated” the microbiota of the fat ones: both groups of mice remained slim.

A similar experiment was conducted by researchers from the University of Michigan Medical School [4]. At first, biologists raised a generation of sterile mice (without intestinal microflora). After that, their intestines were colonized with human bacteria (the material was taken from the feces of a healthy person with a normal body weight). Next, the laboratory rodents were divided into two groups. The first was fed high—fiber food, the second was fed fatty and high-calorie food, which is practically devoid of fiber. Initially, the stool counts in both groups were almost the same, but later significant changes were found. In mice that consumed little fiber, CM changes typical of obesity were found: a decrease in the content of Bacteroidetes in the lumen of the colon and an increase in the number of Firmicutes. It is noteworthy that animals with similar CM changes were able to absorb more fats from the intestine. An increase in the number of Firmicutes-type bacteria in the intestines of fat-fed mice has been found for several months. Only the method of faecal transplantation helped to restore the lost microflora. In this case, ten days after the procedure, the composition and diversity of rodent intestinal bacteria from different groups could no longer be distinguished. According to scientists, the decline in diversity KM is one of the causes of obesity, and the intake of fatty foods with low fiber contributes to this [1], [5].

A similar effect on high-fat food intake has also been found in humans. An increase in caloric intake from 2,400 to 3,400 kcal/day, both in obese and non-obese people, led to rapid changes in CM: a 20% increase in the number of Firmicutes and a corresponding decrease were observed in faeces Bacteroidetes [6].

Based on the results of these experiments, we can assume that the body still has a population of bacteria responsible for obesity and a population responsible for weight loss. And the intake of fatty, low-fiber foods contributes to changes in CM towards an increase in the population of bacteria that contribute to overweight [7].

How can the gut microbiota cause obesity?

Of course, we cannot say that dysbiosis is the only cause of obesity, as it is a polyethological process. Nevertheless, it, along with other predisposing genetic, environmental, and social factors, can lead to metabolic disorders in the body. Obesity occurs when the intake and production of energy exceeds its demand, and the remainder of the unused resources is deposited in adipose tissue.

What is one of the main sources of energy in the body? Of course, it’s glucose. The results of the experiment [8] revealed that in mice with elevated blood glucose levels (suffering from diabetes mellitus), the composition of the intestinal microflora is similar to that of obese mice. This means that these processes are closely related to each other [9].

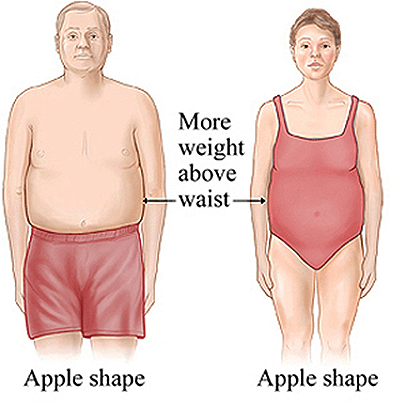

Of course, not all overweight people have diabetes, but 80% of people with diabetes are obese and more often of the abdominal type, in which fat deposits are mainly formed in the abdominal area. This type of figure is popularly called an “apple”.

Let’s try to understand the mechanism by which glucose contributes to obesity. Glucose entering the bloodstream increases the production of insulin (a hormone that regulates blood glucose levels). Insulin, in turn, stimulates fat synthesis and deposition (by increasing the activity of lipogenesis enzymes, primarily the ATP-dependent citrate-cleaving enzyme) and inhibits their breakdown [5]. At the same time, if a person leads a “sedentary” lifestyle, the synthesized lipids are deposited in adipocytes (since the energy coming from outside is not used and has to be stored as adipose tissue).

But these processes occur all the time in a healthy body. This means that in order for lipogenesis to go beyond the norm, you need either a lot of glucose, or little insulin, or a violation of the interaction of insulin and glucose. Since the mice from the experiment described above were fed feeds with a high percentage of fats, not carbohydrates, it means that it is not an excessive intake of glucose into the body. Insulin is produced by beta cells of the pancreas, and in mice from previous experiments, the function of the gland was not impaired. This indicated that the problem was not an insulin deficiency. Although in 2015, scientists put forward a theory about the direct connection of bifidobacteria (pic. 4) with the synthesis of a glucagon-like peptide.-1 [8], [10]. Glucagon-like peptide—1 is an incretin, that is, it is produced in the intestine in response to oral food intake. It has an effect on various organs and systems, including enhancing insulin secretion. The peptide is produced by L-cells located in the mucous membrane of the ileum and colon, and bifidobacteria can stimulate its synthesis. Accordingly, if the number of bifidobacteria in the intestine decreases, then the amount of this peptide decreases, and therefore the level of insulin. But this theory still requires detailed study, so we cannot yet name it as the main reason for the increase in sugar in the body. This means that there is still an option with impaired glucose uptake.

Intestinal microbiota and type 2 diabetes mellitus

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM II or non-insulin-dependent diabetes) — this is a metabolic disease that is manifested by a violation of carbohydrate metabolism. As a result of pathological changes — the acquisition of insulin resistance, that is, the body’s cells are immune to this hormone — hyperglycemia develops (an increase in the concentration of glucose in the blood). In simple words, the body has normal insulin levels and elevated glucose levels, which for some reason cannot enter the cells. Let’s look at the mechanism of formation of insulin resistance.

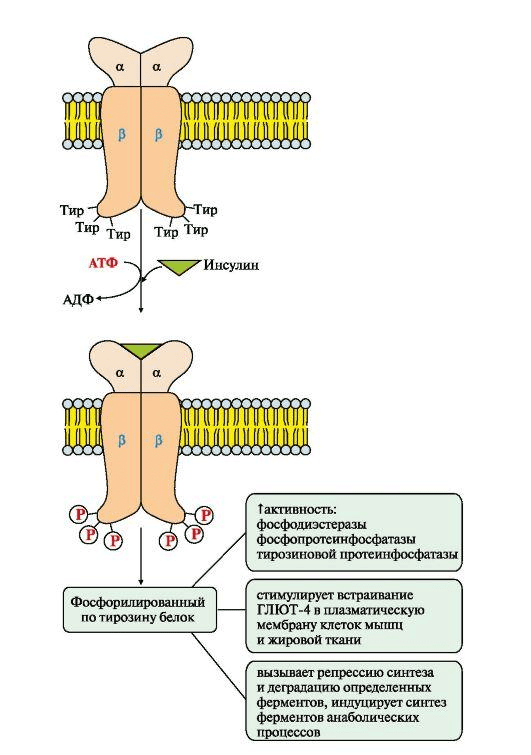

In Figure 5, we see the insulin receptor, which consists of two subunits.:

- α — reacts with insulin outside the cell;

- β is a subunit that is already associated with secondary messengers, type 1 and type 2 insulin receptor substrates.

The insulin receptor is a tyrosine kinase [12]. Through autophosphorylation, various pathways are activated, in particular, the PI3K (phosphoinositide-3-kinase) pathway, due to which glucose is transported into the cell, as the GLUT4 glucose transporter enters its active working state. This is how glucose enters the cell normally.

The scheme of activation of the insulin receptor

Let’s consider what happens to this mechanism in dysbiosis [7]. The number of harmful bacteria in the body increases, which, when interacting with receptors on the intestinal walls, can cause inflammation and activate the immune system. Have you ever wondered why our body doesn’t reject beneficial microorganisms and how it distinguishes which ones are beneficial and which ones are harmful? This is because enterocytes, goblet-shaped, dendritic and endocrine cells are present in the intestinal wall, which, in addition to performing their main function, contain toll-like receptors (English toll-like receptor, TLR; from German. toll is wonderful) [13]. These receptors are involved in the recognition of “own” and “foreign” microorganisms. Toll-like receptors respond to pathogen-associated molecular structures. Despite the fact that there are 10 varieties of these receptors, each of them recognizes only its “marker” part of the microorganism. For example, TLR4 recognizes bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), TLR2 recognizes bacterial peptidoglycan and lipopeptide, TLR3 recognizes double—stranded RNA molecules, TLR8 recognizes single—stranded RNA molecules, and TLR9 recognizes bacterial DNA. Due to these receptors, our body does not respond with an inflammatory reaction to the presence of normoflora in the intestine. If the ratio of beneficial and transient microflora is disrupted in it, toll-like receptors are excited and transmit an alarm signal into the cell, which leads to the activation of the production of a number of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and co-stimulation molecules (which induce the excitation of T-lymphocytes). As a result, inflammation develops as a protective reaction of the body from non-specific immunity, and the first steps are being taken to develop specific (adaptive) immunity.

What does insulin resistance have to do with it, you ask? It’s pretty simple.: These toll-like receptors, upon contact with a pathogenic organism, stimulate an immune response in the hope of dealing with a stranger. During cascade reactions, the macrophage system is stimulated. Activated M1 macrophages (they are also called classically activated macrophages, they are responsible for the destruction of foreign agents) produce a large number of pro-inflammatory cytokines: TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha), IL-1 (interleukin-1) and IL-6, which affect the substrates of the insulin receptor and thereby block the pathway PI3K [14]. As a result, the pathway has no effect on glucose metabolism, and glucose cannot enter the cell. In this way, insulin resistance develops, because insulin receptors become insensitive to insulin, and its biological role is distorted. In conditions of insulin resistance, the liver begins to actively synthesize fatty acids and triglycerides, and lipolysis accelerates, but already in adipose tissue.

So we have analyzed the mechanism of insulin resistance and its effect on obesity. Scientists have confirmed the role of microbiota on insulin resistance experimentally [15] by transplanting microflora from a healthy donor to a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus. As a result of the experiment, patients’ insulin sensitivity increased for several weeks. There is also an interesting theory about the relationship between TLR5 deficiency and obesity [16], but this is a completely different story.

Conclusion

It is necessary to approach the problem of obesity comprehensively. A physically active lifestyle, a rational diet that avoids overeating, calorie restriction, a decrease in saturated fatty acids (animal fats), a relative increase in unsaturated fatty acids (vegetable fats) and foods with a high content of dietary fiber remain the main measures in the prevention and treatment of obesity. At the same time, if it is possible to confirm the contribution of specific microorganisms to weight loss, then effective probiotic drugs may be created that will be included in comprehensive obesity treatment programs.

Anastasia Nikolaeva

Source: Biomolecule

Published

July, 2024

Duration of reading

About 5-6 minutes

Category

Microbiome

Share