The zoo in my stomach

There are as many bacteria in your body as there are your own body cells. And the digestive system, a particularly favorable place for bacteria, is literally full of them. But the portable microbiological museum is not limited to bacteria: a huge variety of viruses, archaea, fungi and protozoa constantly live in the body. But take your time to disinfect: the microbiome is an absolutely necessary part of a healthy person’s body, without which we would not be able to eat many foods, would suffer from immune problems, as well as from many infections that usually bypass us. Let’s learn more about our microscopic neighbors, who almost selflessly make everyone’s life more enjoyable.

The intestine is too wonderful a place to remain uninhabited. It is warm, it receives food regularly, it is protected from the weather, predators and many other blows of fate. It is not surprising that the intestines of any animal are home to many microorganisms that make up its microflora (microbiome, microbiota). For its part, the animal can only make sure that the microbes do not multiply too much and that among the microscopic passengers there are as many useful or at least harmless creatures as possible. You need to start working on this right from birth.

Formation of intestinal microflora

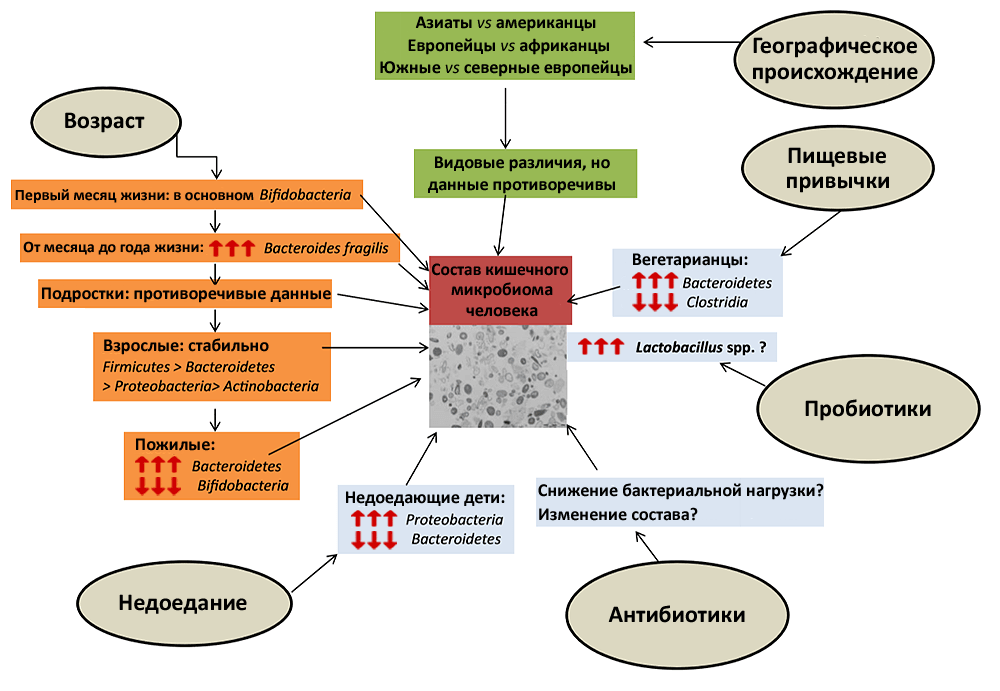

Newborn mammals are poorly able to take care of themselves and therefore cannot take reasonable steps to create a favorable microflora in their intestines. This role is assumed by the mother: her milk contains not only microorganisms, but also antibodies [1], immune cells and cytokines, which help to properly organize the interaction of the infant’s immune system with its new life partners [2]. In addition, milk contains substances that stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria: in particular, certain oligosaccharides promote the reproduction of bifidobacteria [3]. The fact that the baby receives the first microbes from the mother affects his later life: the microflora of the mother and her child is more similar than that of two randomly selected people. At the same time, the bacterial communities of the intestines of fraternal twins are similar to the same extent as in fraternal twins. Since the genetic information of identical twins is identical, and that of fraternal twins is no more similar than that of brothers born at different times, it turns out that the genetic component has only a minor effect on the formation of the bacterial microbiota. The main contribution to its development is made by external conditions (Pic. 1) [4].

Picture 1. The main external factors affecting the composition of the microflora. Genetics makes only a minimal contribution to the microflora, but the circumstances of a person’s life can affect it very significantly. Moreover, some factors — for example, antibiotics or an abrupt change in diet — require only a few days to do this (although short-term effects cause quickly reversible changes). The red arrows pointing upwards indicate an increase in the proportion of a particular group of bacteria in the intestinal microbiome, and vice versa.

A full-fledged microflora, the diversity of which is as great as in adults, is formed in a child by the age of three [5]. Up to this age, the immune system is more tolerant of microbes, since the child is just filling out his micro zoo. This is one of the reasons why young children are particularly susceptible to infections. But when the microflora finally forms, its benefits will pay off the sacrifices and dangers of the first years of life.

Immunity and microbiome

The immune system must handle the microbiota very carefully: on the one hand, it must allow microbes to live peacefully in a designated place (the intestine), but on the other hand, it must react promptly when they violate established boundaries or begin to multiply too actively. It would seem that this additional burden on the immune system, which should already be sensitive to all health threats, should make it more difficult to maintain homeostasis. Surprisingly, this is not the case.

Experiments show that in the absence of microbiota, the immune system develops and functions much worse. This led scientists to the idea that the host uses microscopic roommates as a kind of simulator that allows you to keep the immune system in good shape. To test this, as well as many other assumptions about the role of microbiota, scientists are investigating gnotobiotic mice, animals that are raised under carefully controlled conditions, so that researchers know exactly the composition of their microflora. Gnotobiotic mice may either have no microbiota at all, or it may consist of a strictly defined set of species introduced into their bodies by scientists.

It turned out that mice without microbiota produce fewer CD4+ T cells and plasma cells that produce IgA antibodies [6]. And in the intestines of such animals, the structure of lymphoid follicles is disrupted — important organs of the immune system in which B-lymphocytes acquire receptors that help them recognize harmful molecules [7]. In addition, the microbiota is necessary to teach the immune system healthy tolerance, so that it does not try to attack, for example, incoming food. It has been shown that active suppression of inflammatory processes that can develop in response to food antigens is impossible without a microbiome [8]. Gut bacteria also play a role in triggering antiviral responses. Most of the T cells that produce interferon-gamma (a substance that suppresses the spread of viruses) are found in the digestive tract. And it is specific local bacteria that stimulate the synthesis of interferon-gamma by these cells [9].

In addition to the complex molecular interactions that help the microbiome stimulate the immune system to work more efficiently, the microbiota has an easier way to help the immune system. Permanent representatives of the microflora compete with other microbes for certain metabolites and simply do not leave resources for the life of extraneous, potentially dangerous microbes. In addition, microbiota regulation of the composition of the environment affects the activity of virulence genes of pathogenic microorganisms (for example, Salmonella enterica and Clostridium difficile) [10].

Microflora and nutrition

Microorganisms are able to feed on substrates that, fortunately, most people never dreamed of. This means that the diversity of digestive enzymes in microbes is much higher than in humans. It’s a sin not to take advantage of this, since bacteria and other microorganisms inevitably colonize the intestines. Microbes capable of breaking down cellulose (fiber) live in the human digestive tract — the main complex carbohydrate of plants. Not all cellulose from plant foods is digested in our intestines, but without the microbiota, it would be energetically unprofitable to eat plants at all.

Bacteria not only help us break down substrates that we cannot digest ourselves, but also synthesize useful compounds that are absorbed into the intestine along with food. For example, bacteria synthesize vitamin K, B vitamins, and tetrahydrofolate, a coenzyme necessary for amino acid metabolism [11]. In addition, bacteria help us absorb minerals, primarily iron. Mice with a normal microbiota can live on a low-iron diet for a long time, because the bacteria secrete special proteins that allow them to capture these ions with high efficiency. But mice without microbiota develop anemia with low iron content in food [12].

Interestingly, the composition of the intestinal microflora varies depending on the diet. Thus, it has been shown that residents of Western countries, whose diet is rich in proteins and animal fats, have more bacteria in their microbiota. Bacteroides, and the inhabitants of poorer regions (African villages, Venezuela), in which people eat mainly plant foods rich in complex carbohydrates, are dominated by species of the genus Prevotella [13]. Interestingly, similar changes in the microbiota associated with different lifestyles are typical for urban and rural residents [14].

How long does it take for the diet to affect the composition of the microflora? An experiment by American scientists has shown that in extreme cases, for diets consisting only of plant or animal products, four days is enough [15].

Geography of the microbiome

As it turned out, in the human microbiota, it is possible to trace the features associated with the region of his residence. For example, a bacterium Bacteroides plebeius, which helps digest the glycans of seaweed (nori and others), has so far been found only in Japanese. Interestingly, the glycoside hydrolase gene, which allows Bacteroides plebeius digests seaweed, has been found in bacteria that live permanently on such algae. It is very likely that this gene got into the Japanese microbiota from them by horizontal transfer [16].

Another useful microbe, Lactococcus garvieae, is also common among Asians. When digesting soy, this bacterium secretes S-equol, a compound that prevents the development of menopausal symptoms and certain types of tumors [17] due to its interaction with estrogen receptors. This explains the positive effect of soy consumption in the fight against cancer. But the bacteria that make it manifest are not nearly as common in Caucasians as in Asians: in Western countries, about one in four people, and in China, Korea and Japan has one in two.

Some national features of the microbiome have not yet been explained. For example, it is still unclear why Italians have two to three times more bifidobacteria than residents of other European countries [18]. Nevertheless, such characteristic features of the microbiome are interesting to study: even if their causes are not clear, they can tell a lot about the history of mankind. Regional differences begin to appear from a very young age. Thus, it was shown that six-month-old Finns and residents of the African Republic of Malawi have a proportion of bifidobacteria, representatives of Bacteroides-Prevotella, as well as the pathogen Clostridium histolyticum, differ significantly [19]. It turns out that the region in which the child was born is of great importance for his future microbiome.

Microbiome and diseases

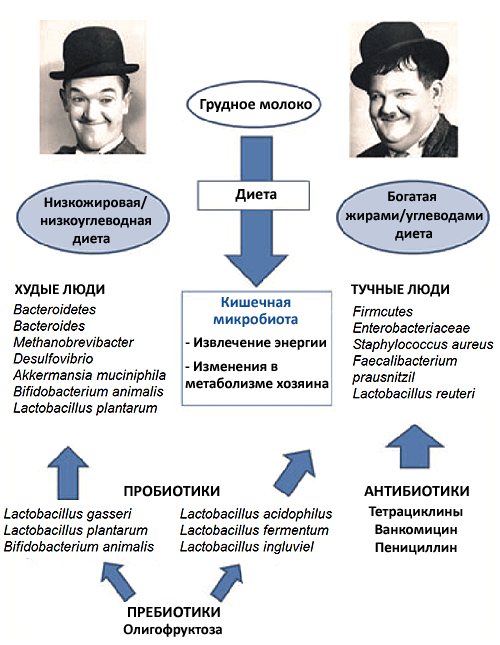

The microbial communities that inhabit our body are rich in species and complex. This is especially true for the intestine, where both the number of bacterial species and the density of microbes per unit of space are impressively high. Each person’s gut forms a separate ecosystem with complex feedback loops that control the abundance of different microbes. Violations of a favorable species balance can lead to a variety of health problems. For example, it has been found that obesity reduces the diversity of intestinal microflora species (Fig. 2). Moreover, experiments show that changes in microflora relate to the causes of obesity, not to its consequences. If the intestines of mice without microbiota are populated with bacteria from obese mice, the animals will gain weight faster than in the case of transplantation of the intestinal microbiota of lean mice [20]. Knowing only the composition of the microbiota, it is possible to determine whether a person is obese, with a probability of 90% [21].

Picture 2. The influence of the intestinal microbiota on the development of obesity. A number of studies have shown that changes in the intestinal microflora in obese humans and animals are not a consequence, but one of the causes of excess weight. Compared to the microflora of people with normal weight, the microflora of obese people is poorer, and the ratio of bacteria of different groups in it is different. Owners of such microflora gain weight faster than “ordinary” people, even with absolutely identical diets.

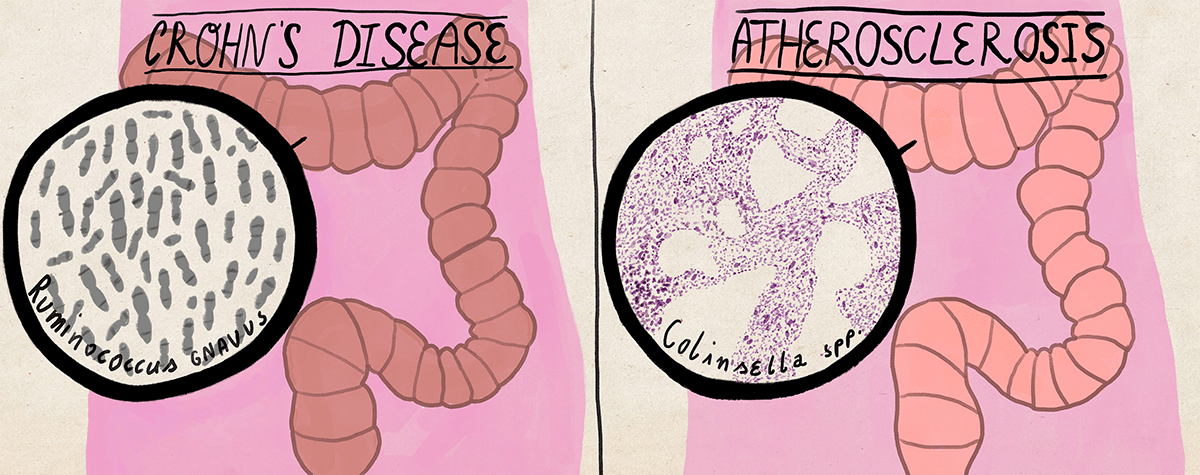

The diversity of the intestinal microbiota decreases both in recurrent pseudomembranous enterocolitis [22] and in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases [23]. In Crohn’s disease, which belongs to the latter, numerous representatives of Faecalibacterium and Roseburia usually disappear in the ileum, and Enterobacteriaceae and Ruminococcus gnavus take their place.

Diseases that are not directly related to digestion can be associated with changes in the bacterial composition of the intestinal microflora. Thus, patients with symptoms of atherosclerosis are characterized by an increase in the proportion of intestinal bacteria Collinsella due to a decrease in the proportion of Roseburia and Eubacterium [24], and the presence of bacteria Helicobacer pylori reduces the likelihood of asthma and allergies [25]. Interestingly, pathogenic strains of the same Helicobacter pylori provoke the development of gastritis (at least). That is why it is not enough to know the specific composition of intestinal microbes in order to draw conclusions about human health, but it is also necessary to take into account their strains — intraspecific groups, which can vary greatly in pathogenicity and other properties.

Studies in mice have shown that both the presence of pathogenic bacteria in the digestive tract [26] and the development of inflammatory bowel diseases [27] increase anxiety in animals.

Antibiotics and microflora

Antibiotics (antibacterial drugs) act not only on pathogenic microbes, but also on beneficial representatives of the microbiome, significantly affecting the body. Taking antibiotics can change the stable state of the microbiota [28], and the effect can persist for years [29]. Not only the composition of the microbial community established after the use of antibiotics is maintained stable, but also the expression of antibiotic resistance genes by its members — that is, over time, bacteria do not lose their resistance to drugs.

In the absence of selective pressure, resistance genes spread weakly among intestinal bacteria [30], but if antibiotics are used, the efficiency of horizontal transfer will increase, which means that resistance genes will be transmitted more actively [31]. In addition, antibiotics are one of the types of stress that trigger SOS repair, which leads to the appearance of many mutations and the appearance of new resistance genes [32]. Therefore, antibiotics not only promote the growth of resistant bacterial populations, but also create new ones, facilitating horizontal gene transfer and the emergence of new types of resistance. In the long term, any use of an antibiotic brings closer the time when it will turn from an effective drug into a useless substance. This is also why it is better to take antibiotics only if absolutely necessary and according to a doctor’s prescription.

The depletion of the microbiome by antibiotics not only leads to unpleasant symptoms (for example, diarrhea), but also reduces the resistance of the entire community to pathogenic bacteria [33].

Pro- and prebiotics

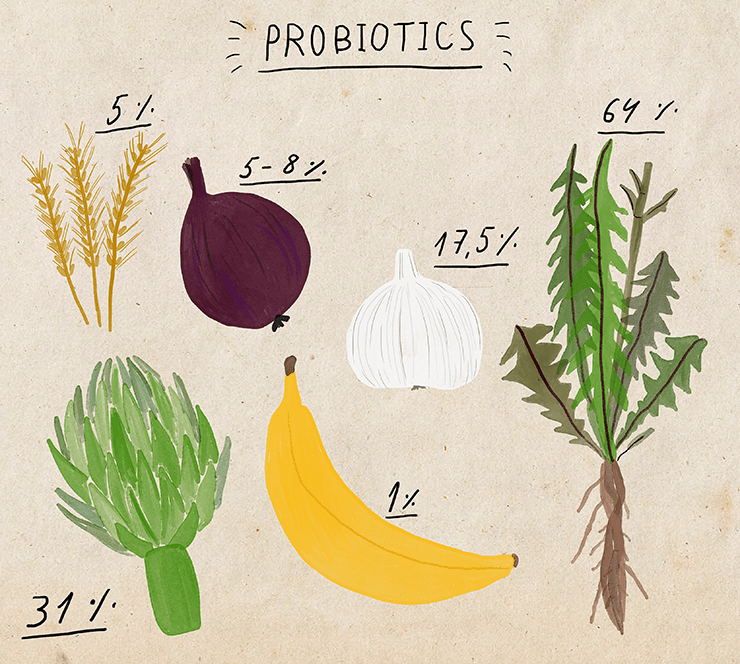

Pro- and prebiotics are drugs that can help restore the microflora after its disruption, for example, due to taking antibiotics. Probiotics are cultures of beneficial microorganisms, most often they include bifidobacteria and lactobacilli [34]. Prebiotics are substances (substrates) that stimulate the growth of such bacteria: for example, inulin, fructose and galactose oligosaccharides, dietary fiber (in particular, polysaccharides that humans cannot digest without the help of bacteria). Prebiotics are available as dietary supplements, but they are already found in large quantities in many foods that can support the growth of beneficial bacteria: cereals, chicory, legumes, garlic, onions, bananas.

Probiotics are also sold in the form of special preparations (dietary supplements), but they can also be purchased as part of various fermented milk products with bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. Yogurt manufacturers actively fund research on the effects of probiotics on various aspects of human life. In such cases, one can often expect a strong bias in the publication of results: results that are mostly beneficial to sponsors will be advertised, while neutral or negative data will remain unknown to the public. Indeed, there is reason to think that the published data on the positive effects of probiotics are too good, even if we consider all the published results to be honestly obtained. In particular, fewer papers are published than they should in which the effect of probiotics is slightly weaker than the average for all studies [35]. Therefore, when reading about probiotics, we need to remember that we are most likely not being offered all the information about their effects.

Nevertheless, what is known looks very good. According to some studies, probiotics help with irritable bowel syndrome [36], diarrhea caused by antibiotics [37] or chemotherapy [38], enterocolitis [39] and lactose intolerance [40]. The beneficial effects of probiotics are not limited to beneficial effects on digestion. It has been shown, for example, that preparations of strains Lactobacillus. They help fight anxiety if you start using them in the early stages of long-term stress [41]. The microflora affects the level of corticosterone, the main stress hormone, so probiotics can help you feel better not only physically, but also mentally.

Microbiota transplantation

Probiotics are designed to be consumed with food — that is, the bacteria must successfully pass through the stomach with an aggressive acidic environment in order to reach their destination. This is not a very effective delivery method, and a significant portion of the bacteria in probiotic preparations may not survive such a journey. Therefore, sometimes the donor microbiota (in the form of homogenized feces) is inserted directly into the part of the intestine where it should be located using a colonoscopy. This is much more efficient than delivering bacteria with food, but also much more time-consuming, so there is still little data on such therapy. Nevertheless, it is already known that pseudomembranous enterocolitis is successfully treated with this method, and half a century ago, it was possible to cope with its lightning-fast forms with mortality rates reaching 75% using a simple fecal enema [42]. There are also isolated cases of microbiota transplantation being used to treat irritable bowel syndrome, various inflammatory bowel diseases, and metabolic syndrome [43].

Microbiota and cancer

Particularly severe forms of diseases associated with the appearance of pathogenic bacteria or a violation of the balance of microflora species can lead to cancer. For example, atrophic gastritis and sometimes cancer that develops during the development of this disease are associated with the proliferation of pathogenic strains of Helicobacter pylori bacteria [44]. And many cases of colon cancer are associated with the proliferation of Fusobacterium spp., Streptococcus gallolyticus, some representatives of the Enterobacteriaceae family and enterotoxigenic strains Bacteroides fragilis [45]. Even an unhealthy diet can lead to cancer through the microbiota: with a high fat content in food, bacteria begin to produce more deoxycholic acid, which contributes to the development of liver cancer [46]. The risk of cancer formation due to a violation of the normal microbiota is another reason why the importance of caring for the microscopic population of the human body cannot be overestimated. The good news is that the risk of developing cancer associated with digestive tract bacteria can be predicted by examining the microbiome [44, 47].

Even if the situation is out of control, the microflora can still help the body fight cancer. For example, the following mechanism is described: not only tumor cells, but also intestinal cells suffer from the action of the chemotherapeutic drug cyclophosphamide. Microorganisms go outside, and the immune system is activated to cope with the spread of microflora outside the intestine. At the same time, the increased activity of the immune system helps the body fight cancer [48].

Microbiota and medicines

Recently, more and more drugs have been discovered, the effect of which is influenced by the microbiota. Bacteria can modify drug molecules by affecting their metabolism. And sometimes such modifications are simply necessary for medications to work. An interesting example is some oriental medicine products that do not work on people who do not have certain bacteria in their microflora. For example, ginseng does not have a beneficial anti-inflammatory effect on approximately one out of five people [49]. The composition of intestinal bacteria determines the effectiveness of the popular analgesic paracetamol (acetaminophen). Its metabolism depends on the level of p-cresol, a microbial metabolite that competes with paracetamol for binding to the enzyme that attaches the sulfogroup. The more microbial p-cresol there is, the less often sulfogroups attach to paracetamol molecules [50].

Some intestinal bacteria themselves produce substances with medicinal properties. For example, Clostridium sporogenes secretes indole-3-propionic acid, an antioxidant and a potential remedy against Alzheimer’s disease [51].

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Published

July, 2024

Duration of reading

About 3-4 minutes

Category

Microbiome

Share

List of sources

- What do newborns owe to the CCR10 receptor;

- P. F. Perez, J. Dore, M. Leclerc, F. Levenez, J. Benyacoub, et. al.. (2007). Bacterial Imprinting of the Neonatal Immune System: Lessons From Maternal Cells?. PEDIATRICS. 119, e724-e732;

- A. Marcobal, J.L. Sonnenburg. (2012). Human milk oligosaccharide consumption by intestinal microbiota. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 18, 12-15;

- Peter J. Turnbaugh, Micah Hamady, Tanya Yatsunenko, Brandi L. Cantarel, Alexis Duncan, et. al.. (2009). A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 457, 480-484;

- Yatsunenko T., Rey F.E., Manary M.J., Trehan I., Dominguez-Bello M.G., Contreras M. et al. (2012). Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 486, 222–227;

- Sarkis K. Mazmanian, Cui Hua Liu, Arthur O. Tzianabos, Dennis L. Kasper. (2005). An Immunomodulatory Molecule of Symbiotic Bacteria Directs Maturation of the Host Immune System. Cell. 122, 107-118;

- Ohnmacht C., Marques R., Presley L., Sawa S., Lochner M., Eberl G. (2011). Intestinal microbiota, evolution of the immune system and the bad reputation of pro-inflammatory immunity. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 653–659;

- Weiner H.L., da Cunha A.P., Quintana F., Wu H. (2011). Oral tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 241, 241–259;

- Valérie Gaboriau-Routhiau, Sabine Rakotobe, Emelyne Lécuyer, Imke Mulder, Annaïg Lan, et. al.. (2009). The Key Role of Segmented Filamentous Bacteria in the Coordinated Maturation of Gut Helper T Cell Responses. Immunity. 31, 677-689;

- Nobuhiko Kamada, Grace Y Chen, Naohiro Inohara, Gabriel Núñez. (2013). Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota. Nat Immunol. 14, 685-690;

- Andrew L. Kau, Philip P. Ahern, Nicholas W. Griffin, Andrew L. Goodman, Jeffrey I. Gordon. (2011). Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature. 474, 327-336;

- Reddy B.S., Pleasants J.R., Wostmann B.S. (1972). Effect of intestinal microflora on iron and zinc metabolism, and on activities of metalloenzymes in rats. J. Nutr. 102, 101–107;

- G. D. Wu, J. Chen, C. Hoffmann, K. Bittinger, Y.-Y. Chen, et. al.. (2011). Linking Long-Term Dietary Patterns with Gut Microbial Enterotypes. Science. 334, 105-108;

- Tyakht A.V., Kostryukova E.S., Popenko A.S., Belenikin M.S., Pavlenko A.V., Larin A.K. et al. (2013). Human gut microbiota community structures in urban and rural populations in Russia. Nat. Commun. 4, 2469;

- Lawrence A. David, Corinne F. Maurice, Rachel N. Carmody, David B. Gootenberg, Julie E. Button, et. al.. (2013). Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 505, 559-563;

- Jan-Hendrik Hehemann, Gaëlle Correc, Tristan Barbeyron, William Helbert, Mirjam Czjzek, Gurvan Michel. (2010). Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota. Nature. 464, 908-912;

- K. D. R. Setchell, C. Clerici. (2010). Equol: History, Chemistry, and Formation. Journal of Nutrition. 140, 1355S-1362S;

- S. Mueller, K. Saunier, C. Hanisch, E. Norin, L. Alm, et. al.. (2006). Differences in Fecal Microbiota in Different European Study Populations in Relation to Age, Gender, and Country: a Cross-Sectional Study. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72, 1027-1033;

- Łukasz Grześkowiak, Maria Carmen Collado, Charles Mangani, Kenneth Maleta, Kirsi Laitinen, et. al.. (2012). Distinct Gut Microbiota in Southeastern African and Northern European Infants. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 54, 812-816;

- Peter J. Turnbaugh, Fredrik Bäckhed, Lucinda Fulton, Jeffrey I. Gordon. (2008). Diet-Induced Obesity Is Linked to Marked but Reversible Alterations in the Mouse Distal Gut Microbiome. Cell Host & Microbe. 3, 213-223;

- Y. Sun, Y. Cai, V. Mai, W. Farmerie, F. Yu, et. al.. (2010). Advanced computational algorithms for microbial community analysis using massive 16S rRNA sequence data. Nucleic Acids Research. 38, e205-e205;

- Plasmon resonance energy migration: the second life of optical spectroscopy;

- Ben P. Willing, Johan Dicksved, Jonas Halfvarson, Anders F. Andersson, Marianna Lucio, et. al.. (2010). A Pyrosequencing Study in Twins Shows That Gastrointestinal Microbial Profiles Vary With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 139, 1844-1854.e1;

- Fredrik H. Karlsson, Frida Fåk, Intawat Nookaew, Valentina Tremaroli, Björn Fagerberg, et. al.. (2012). Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nat Comms. 3, 1245;

- Yu Chen. (2007). Inverse Associations of Helicobacter pylori With Asthma and Allergy. Arch Intern Med. 167, 821;

- Mark Lyte, Jeffrey J. Varcoe, Michael T. Bailey. (1998). Anxiogenic effect of subclinical bacterial infection in mice in the absence of overt immune activation. Physiology & Behavior. 65, 63-68;

- Bercik P., Park A.J., Sinclair D., Khoshdel A., Lu J., Huang X. et al. (2011). The anxiolytic effect of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 involves vagal pathways for gut-brain communication. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 23, 1132–1139;

- L. Dethlefsen, D. A. Relman. (2011). Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108, 4554-4561;

- Cecilia Jernberg, Sonja Löfmark, Charlotta Edlund, Janet K Jansson. (2007). Long-term ecological impacts of antibiotic administration on the human intestinal microbiota. ISME J. 1, 56-66;

- L. Drago, V. Rodighiero, R. Mattina, M. Toscano, E. de Vecchi. (2011). InVitroSelection and Transferability of Antibiotic Resistance in the Probiotic StrainLactobacillus reuteriDSM 17938. Journal of Chemotherapy. 23, 371-373;

- Время обезьяньих исследований: расшифрован геном макаки резуса;

- Alonso A., Campanario E., Martínez J.L. (1999). Emergence of multidrugresistant mutants is increased under antibiotic selective pressure in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 145, 2857–2862;

- Miller C.P., Bohnhoff M., Rifkind D. (1957). The effect of an antibiotic on the susceptibility of the mouse’s intestinal tract to Salmonella infection. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 68, 51–55;

- Medicinal preparations from living microorganisms;

- Matthieu Million, Didier Raoult. (2012). Publication biases in probiotics. Eur J Epidemiol. 27, 885-886;

- Tina Didari. (2015). Effectiveness of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: Updated systematic review with meta-analysis. WJG. 21, 3072;

- Issa I. and Moucari R. (2014). Probiotics for antibiotic-associated diarrhea: do we have a verdict? World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 17788–17795;

- Michal Mego, Jozef Chovanec, Iveta Vochyanova-Andrezalova, Peter Konkolovsky, Milada Mikulova, et. al.. (2015). Prevention of irinotecan induced diarrhea by probiotics: A randomized double blind, placebo controlled pilot study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 23, 356-362;

- Xiaolin Wang, Zhi Li, Zhilin Xu, Zhongrong Wang, Jiexiong Feng. (2015). Probiotics prevent Hirschsprung’s disease-associated enterocolitis: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 30, 105-110;

- Almeida C.C., Lorena S.L., Pavan C.R., Akasaka H.M., Mesquita M.A. (2012). Beneficial effects of long-term consumption of a probiotic combination of Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Bifidobacterium breveYakult may persist after suspension of therapy in lactose-intolerant patients. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 27, 247–251;

- M. G Gareau, J. Jury, G. MacQueen, P. M Sherman, M. H Perdue. (2007). Probiotic treatment of rat pups normalises corticosterone release and ameliorates colonic dysfunction induced by maternal separation. Gut. 56, 1522-1528;

- Thomas J. Borody, Alexander Khoruts. (2011). Fecal microbiota transplantation and emerging applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9, 88-96;

- Noortje G Rossen. (2015). Fecal microbiota transplantation as novel therapy in gastroenterology: A systematic review. WJG. 21, 5359;

- Yoshio Yamaoka, David Y Graham. (2014). Helicobacter pylori virulence and cancer pathogenesis. Future Oncology. 10, 1487-1500;

- B. Hu, E. Elinav, S. Huber, T. Strowig, L. Hao, et. al.. (2013). Microbiota-induced activation of epithelial IL-6 signaling links inflammasome-driven inflammation with transmissible cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110, 9862-9867;

- Shin Yoshimoto, Tze Mun Loo, Koji Atarashi, Hiroaki Kanda, Seidai Sato, et. al.. (2013). Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature. 499, 97-101;

- Christine M. Dejea, Elizabeth C. Wick, Elizabeth M. Hechenbleikner, James R. White, Jessica L. Mark Welch, et. al.. (2014). Microbiota organization is a distinct feature of proximal colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111, 18321-18326;

- S. Viaud, F. Saccheri, G. Mignot, T. Yamazaki, R. Daillere, et. al.. (2013). The Intestinal Microbiota Modulates the Anticancer Immune Effects of Cyclophosphamide. Science. 342, 971-976;

- James Mitchell Crow. (2011). Microbiome: That healthy gut feeling. Nature. 480, S88-S89;

- T. A. Clayton, D. Baker, J. C. Lindon, J. R. Everett, J. K. Nicholson. (2009). Pharmacometabonomic identification of a significant host-microbiome metabolic interaction affecting human drug metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106, 14728-14733;

- W. R. Wikoff, A. T. Anfora, J. Liu, P. G. Schultz, S. A. Lesley, et. al.. (2009). Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106, 3698-3703;

- Lagier J.C., Million M., Hugon P., Armougom F., Raoult D. (2012). Human gut microbiota: repertoire and variations. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2, 136;

- M. Million, J.-C. Lagier, D. Yahav, M. Paul. (2013). Gut bacterial microbiota and obesity. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 19, 305-313.