Naked digger cells age differently from mouse cells

Naked diggers are often referred to as ‘animals that don’t age’. The authors of a recent article in the journal PNAS found that individual cells of these animals are quite capable of aging. But even under conditions of stress, they do it more economically and safer for the organism than cells of other rodents.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Published

June, 2024

Duration of reading

About 5-6 minutes

Category

Epigenetics

Share

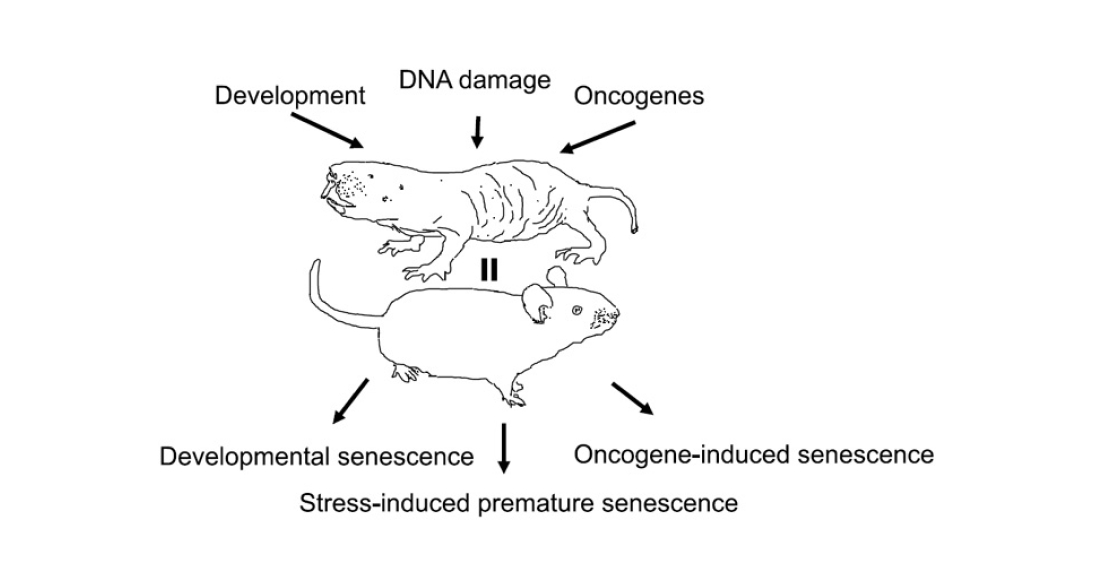

- Replicative senescence. At each cell division, telomeres, the end sections of chromosomes, are inevitably shortened. They themselves do not carry genetic information, but rather serve as ballast protecting the ‘content’ part of the chromosome. But the shorter the telomere, the greater the risk of losing genetic information. Therefore, when the telomere reaches a certain length, the cell cycle stops and division is no longer started.

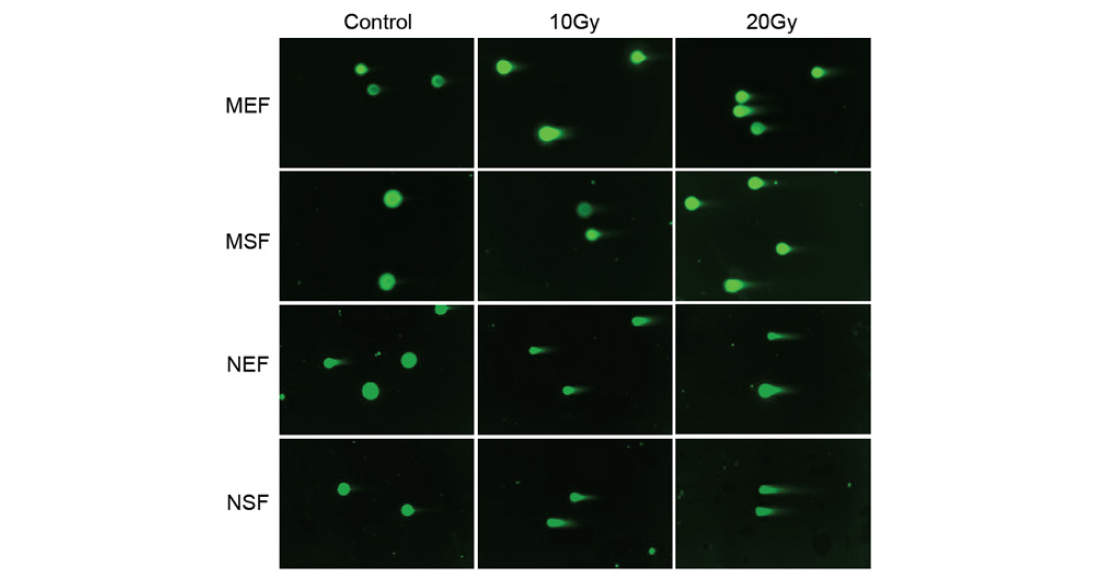

- Stress-induced senescence (SIPS, stress-induced premature senescence). During cellular respiration, molecules with missing or extra electrons – free radicals – are formed in the mitochondria. This is a natural process, which the cell usually regulates with the help of antioxidants – substances that neutralise radicals. But occasionally they manage to escape from the mitochondrion into the cytoplasm or even into the cell nucleus, where they damage macromolecules, including proteins and DNA. The older the cell, the more such damage accumulates in it. DNA repair proteins come into play. When there are enough signals of DNA errors, the repair proteins stop the cell cycle. This is where the free-radical theory of aging comes in. Under the influence of stress factors (starvation, radiation, toxins), the number of radicals increases and oxidative stress develops. If it is strong enough, the cell can age prematurely.

- Oncogene-induced aging. It is believed that cell aging is not only a side effect of accumulating damage, but also a defence mechanism. When a normal cell turns into a cancer cell, the process can still be stopped at the initial stages. As soon as tumour-related genes (e.g. ras) start working actively, the ageing programme starts in parallel. And, if there is no mutation in the genes that stop the cell cycle, it saves the organism from a new tumour. Therefore, premature senescence can be induced in cells by activating ras or other oncogenes in them (see M. Serrano et al., 1997. Oncogenic ras Provokes Premature Cell Senescence Associated with Accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a).

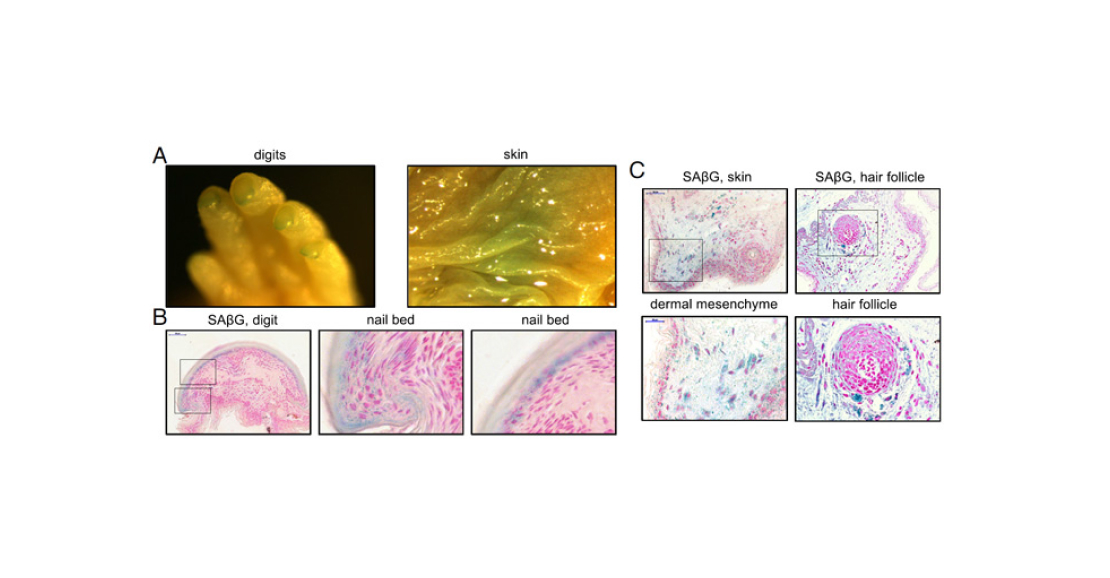

- Programmed senescence (developmental senescence). At certain stages of embryonic development, a part of the cell mass dies off, for example, to form cavities or to remodel tissue. At the same time, the ‘doomed’ cells stop dividing and start the ageing programme. This process depends neither on telomere length nor on the level of stress. It is believed that it evolutionarily preceded stress-induced senescence (see D. Muñoz-Espín et al., 2013. Programmed cell senescence during mammalian embryonic development).

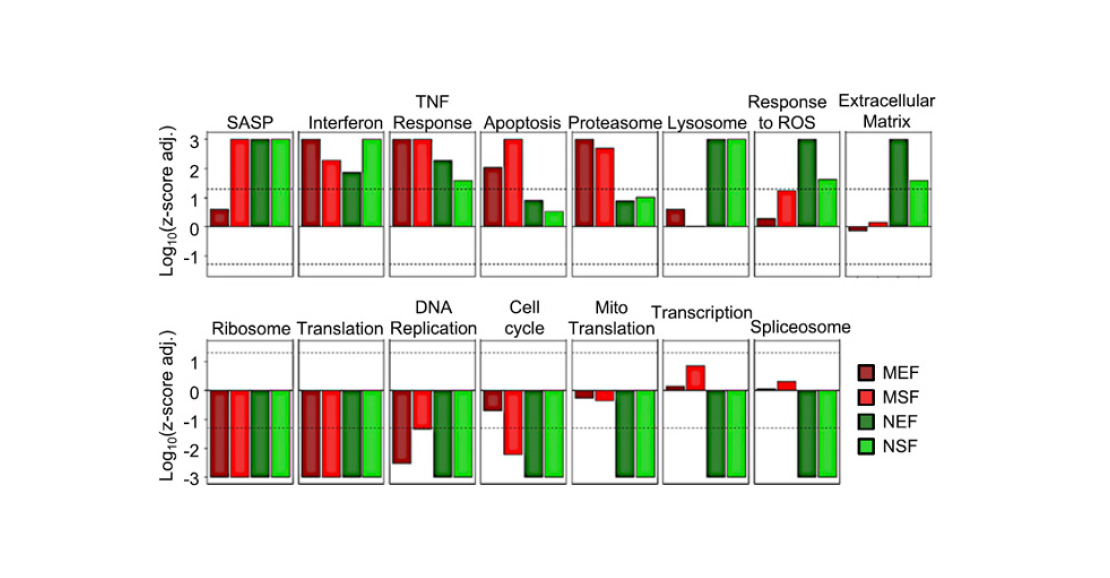

- In all cell cultures, the expression of many genes at once is altered. However, in the mouse, the differences between embryonic and adult fibroblasts are stronger than in the earthworm. This is consistent with the notion that shrews hardly ever ‘grow up’.

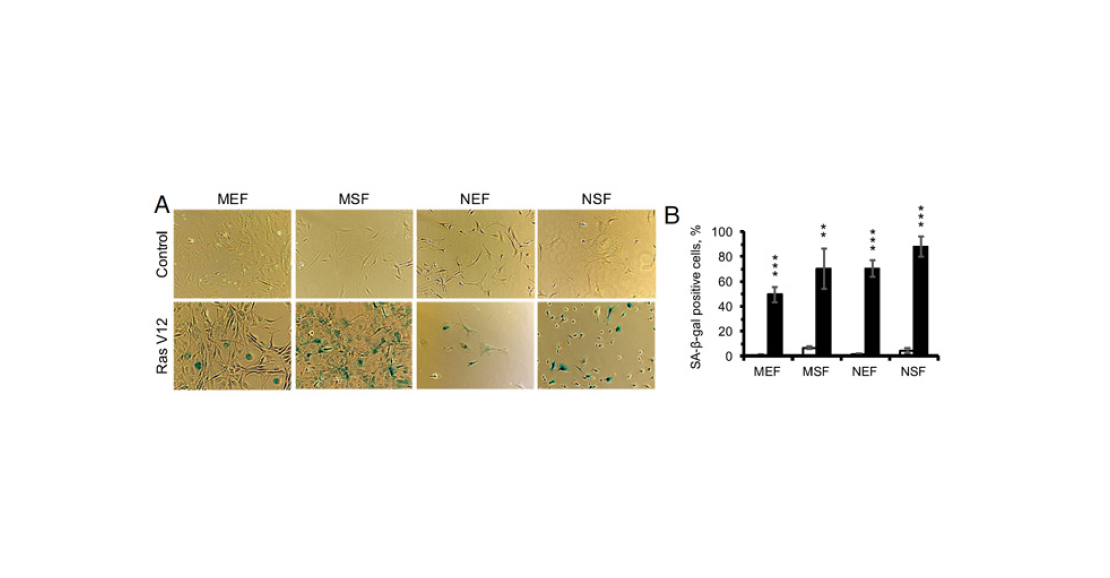

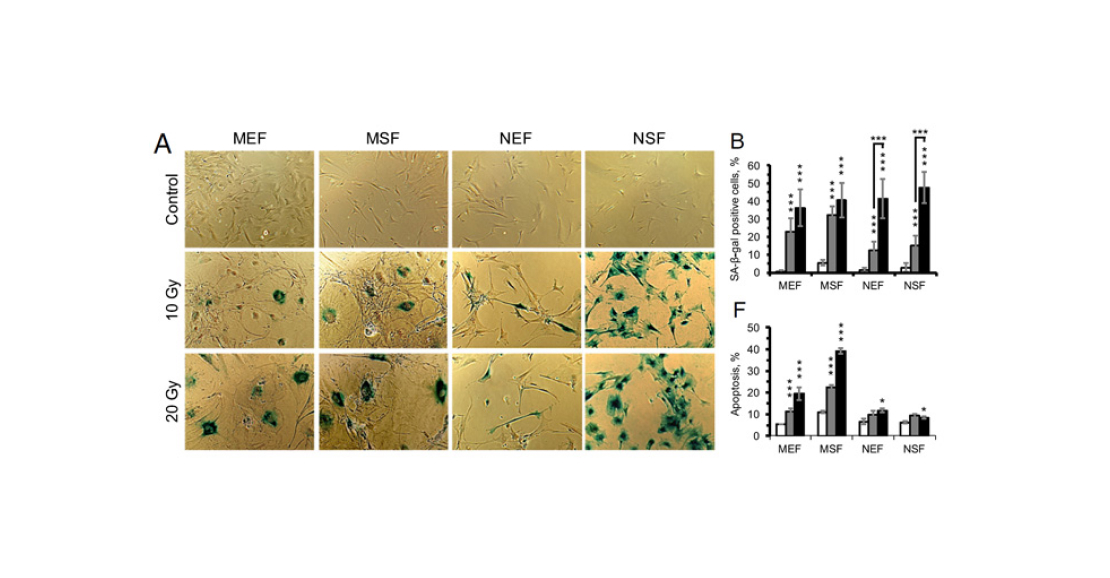

- SASP genes were activated in all cultures. This can be considered as a second confirmation that cell senescence in naked mammals is possible.

- The set of processes triggered and suppressed under stress differs between mouse and shrew. In contrast to mouse cells, the cells of the shrew do not enter apoptosis, as noted above. Also, genes responsible for cellular protein synthesis are suppressed in them, but genes associated with the stress response (breakdown of substances, antioxidants, etc.) are much more active.

- Finally, the most surprising result is the following: while the number of genes that changed expression in response to radiation was greater in shrews than in mice, the number of processes that changed their activity was smaller. This probably means that the aging process in mammals is more clearly organised – fewer genes are triggered enough to regulate more processes.

Source

Scientific Journal Elements. Article: Naked mole rats’ cells age differently than mouse cells