Earlier we found out that amazing African animals – naked mammals – have switched off ageing by applying a clever biological trick. They have so slowed down the process of their individual development that they remain in the state of small cubs for a very long time (decades at least). That’s why they look so much like newborn baby rats. And cubs don’t age, because everything has to start in this life in its own time. Including aging. The crafty earthworms have so rearranged their internal biological clock that it never reaches the ‘OK. You’re an adult now. Start aging.’

Earthworms have been able to deal with aging so boldly because they are true evolutionary innovators. Their numerous and highly organised colonies are so stable that these beasts can afford to slow down their evolution a little. And since aging is a tool for accelerating evolution, the resourceful African rodents can do without it. That is, not grow old.

But speaking of ‘evolutionary champions’, we cannot avoid one species of animals, even more successful than mammals, and especially interesting for us. This species has invented something that no longer needs evolution at all. Its representatives are found in every corner of the globe. They withstand the bitter frosts of the Arctic and Antarctic, the heat of the most terrible deserts. They can be found in the depths of the ocean and even in near space.

It must be said that this is a very young species. If measured by the evolutionary clock, it finally formed only a few seconds ago (scientists argue when exactly this happened, but it is unlikely that it is more than 200,000 years old). And in that time, or rather, just in the last thousand years, it has managed to spread across the planet like this. You’ve probably already guessed which animals we’re talking about. It’s Homo Sapiens, that’s you and me.

What was it that man invented in his development? What made him the evolutionary champion? In my opinion, three things: brains, speech and… grandmothers (and grandfathers).

You know what our most important skill is, what makes us different from other animals? I mean, we have many differences: we are upright, we have a sore thumb on our hand, so we can hold tools in our hands, we can throw objects more accurately than anyone else, and in general, fine motor skills are very good! But, in my opinion, the main peculiarity and uniqueness of a human being is the ability to work with information. And it is this ability that has provided us with such an amazing adaptability to any conditions of existence.

Perhaps this statement needs clarification. As I have already mentioned many times, from the evolutionary point of view, the meaning of life of any living organism is to transmit information. It must pass its genetic information to the next generation. That is, to reproduce, to bring offspring. And by and large, the transferred genes contain all the information necessary for the life of the said offspring. Even the most complex animal behaviour is encoded in their genes. If you take away a newborn beaver from its mother, take it out, raise it and let it go free, it will certainly find some stream in the forest, try to block it with a dam to build a cosy hut with an underwater entrance. Alone, of course, he will not do too well, but nevertheless he can do it all simply on the basis of genes contained in the cells of his body.

And humans? Our main difference even from our closest relatives – great apes – is a more developed brain. And this brain is constantly working. That is, it receives and analyses data, creating new information. In principle, the brains of other animals are busy doing the same thing, but this is the case when quantity turns to quality. The powerful brain of Homo Sapiens produces so much information that it would be a good idea to share it with its relatives. And that’s where we got lucky once again. A very delicate device for transmitting data – our vocal cords – was invented. And the result was human speech. (Don’t get me wrong, animals can communicate too, but on a completely different, primitive level.) And that’s when we won the evolutionary race. Because unlike all other animals, we can transmit huge amounts of information to other generations not only in the form of genes, DNA, but simply in the form of words, through speech. And this gives us a tremendous advantage in terms of survival. Let me explain by example: here is a mountain, and a cave lion has settled behind the mountain. You can’t go there, he’ll eat you.

We have to somehow adapt to these new conditions. How would ordinary animals solve this problem? It would take millions of years for the unfortunate ones to develop a mutation that makes them fear, say, the silhouette of a mountain. The mutation would then take hold in subsequent generations, and the lion would stop eating animals of that species.

How does a man endowed with brains and speech solve this problem? When he sees a lion (or its tracks, which is even more convenient), he simply says to the others: don’t go behind this mountain, they will eat you. Bingo! No need to wait for millions of years of evolution, the problem is solved not just within a generation, but simply within a day. Can you imagine how much more efficient it is to adapt to new conditions like this?

Or let’s say it got colder. Common animals have an evolutionary competition to see who gets the mutation that allows them to have fluffier fur. The process takes many millennia.

And we have one clever person who thinks of wrapping himself in the skin of a dead animal and, of course, tells the rest of us how great it is. Problem solved, no need for millions of years of evolution.

This is great in itself, but it is even more interesting if we ask ourselves: who can pass on information to the next generations? In animals, only the parents. Because information is transmitted only with genes, and we get them from our parents. In humans, not necessarily. We can be terribly useful to our species, even if we’ve lost the ability to reproduce. Because you can explain to young idiots that there’s a cave lion behind that mountain in your old age. An older, experienced teacher is somehow more trustworthy and authoritative.

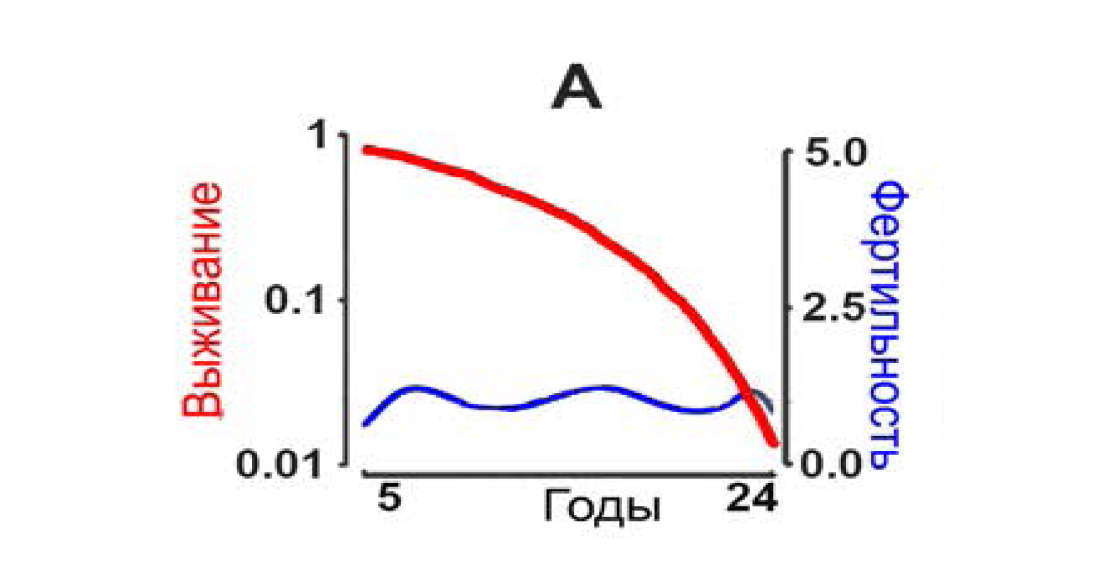

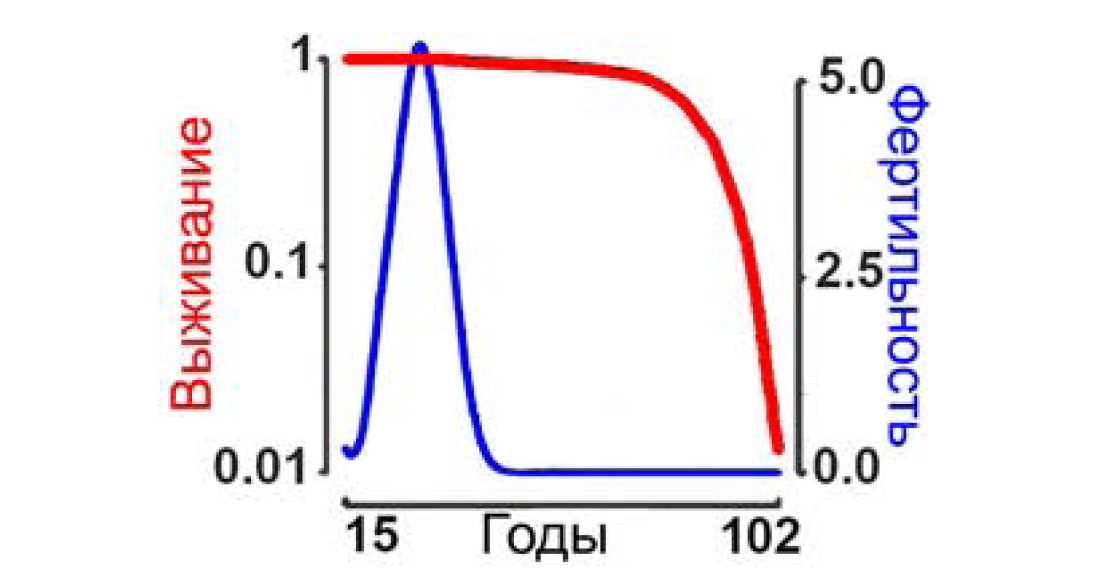

The reasoning is rather banal, but it has an important biological consequence. In short, we humans are allowed to live, even after we are no longer able to reproduce because of age. This is best seen in the following graphs. Look, here are two curves showing the relationship between survival (red) and ability to reproduce (blue) in our close relative, the baboon.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox