Naked digger cells age differently from mouse cells

Naked diggers are often referred to as ‘animals that don’t age’. The authors of a recent article in the journal PNAS found that individual cells of these animals are quite capable of aging. But even under conditions of stress, they do it more economically and safer for the organism than cells of other rodents.

Naked mammals (Heterocephalus glaber) live about 10 times longer than their distant relatives – mice and rats. While mice in standard laboratory conditions live to 3 years at best, diggers can live more than 30. It is also suspected that they hardly ever grow to adulthood. Many of the traits that are characteristic only of newborn mice can be observed in diggers throughout or nearly all of their lives. These include lack of cover, small (compared to other mammals) size, and sexual immaturity (mammals mature rather late), as well as the work of some enzymes, erratic body temperature, and active formation of new neurons in the brain. Together, these signs allow us to speak of neoteny, that is, developmental retardation, in which the organism is essentially a ‘child’ for most of its life but functions as an adult (see V. P. Skulachev et al., 2017. Neoteny, Prolongation of Youth: From Naked Mole Rats to ‘Naked Apes’ (Humans)). Finally, it is known that mole rats do not age in the sense we are accustomed to. At least, they extremely rarely die from ‘senile’ diseases – cancer, cardiovascular diseases and neurodegeneration (see: What do naked mole rats and ‘naked apes’ have in common?, ‘Elements’, 06.03.2017). But does this mean that their aging mechanisms are completely switched off?

The authors of the discussed article in the journal PNAS tested whether at least some elements of aging can be detected in naked mammals. Strictly speaking, the answer to this question depends on what we mean by ‘aging’. If we consider the organism as a whole, then aging is often referred to as an increase in mortality with age: after a certain limiting age, a pattern is observed: the older the organism, the greater the probability of dying (there is no such pattern in infancy and reproductive age). In this sense, mole-rats are not susceptible to old age (see J. G. Ruby et al., 2018. Naked Mole-Rat mortality rates defy gompertzian laws by not increasing with age). But if we go down to the level of individual cells, the criteria for old age become much less obvious. Neither the level of mortality (not every dying cell in an organism is old), nor the ability to reproduce (even in a newborn organism not all cells divide), nor the presence of ‘diseases’ (for example, cancer cells contain ‘errors’ in DNA and do not function as usual, but at the same time they actively divide and do not resemble old cells) are suitable here.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Published

June, 2024

Duration of reading

About 5-6 minutes

Category

Epigenetics

Share

Pic. 1. Naked mole rats (Naked mole rat, Heterocephalus glaber) are very unusual animals: compared to other rodents, they live much longer, have a complex social life structure, low body temperature and other physiological features, and are able to not feel some types of pain. Photo from flickr.com.

There is still no unambiguous definition of cellular senescence. Cellular senescence (cellular senescence) is a physiological state in which the cell does not divide, does not differentiate and changes its metabolism. There are currently two ways to detect old cells.

The first is by staining for β-galactosidase (β-galactosidase). This enzyme breaks down sugars during intracellular digestion. It is normally active at neutral values of acidity and is weak in acidic environments. But in the course of aging, the cell begins to produce it in large quantities, so even in an acidic environment its activity can be detected. For this purpose, cells are treated with a dye precursor that acquires a blue colour after cleavage by β-galactosidase (see G. P. Dimri et al., 1995. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo).

The second way is to examine what the cell releases into the environment. Old cells are characterised by a specific set of secreted proteins – SASP (senescence-associated secretory phenotype). This includes, among others, pro-inflammatory proteins, metalloproteinases (which break down intercellular matter) and growth factors (which stimulate the division of other cells). Through these substances, the old cell affects its environment: it forces those still capable to divide, and attracts immune cells to remove decayed cells (including itself) and elements of intercellular matter. Looking for SASP proteins is a more difficult task than staining, but the result is more accurate.

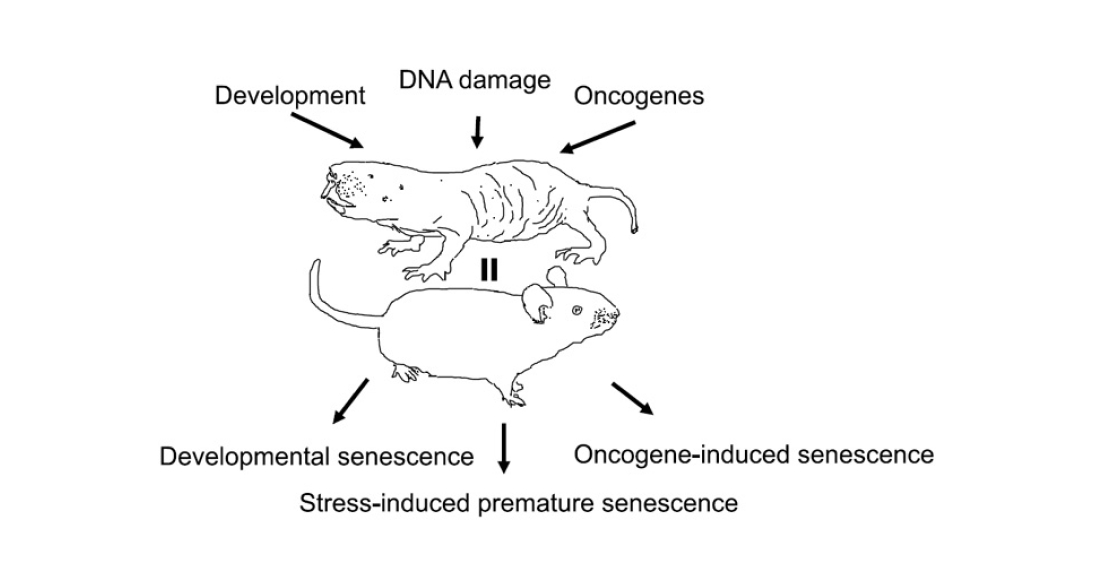

The causes of cell aging are also still ambiguous. At least four independent mechanisms can be identified (Fig. 2):

- Replicative senescence. At each cell division, telomeres, the end sections of chromosomes, are inevitably shortened. They themselves do not carry genetic information, but rather serve as ballast protecting the ‘content’ part of the chromosome. But the shorter the telomere, the greater the risk of losing genetic information. Therefore, when the telomere reaches a certain length, the cell cycle stops and division is no longer started.

- Stress-induced senescence (SIPS, stress-induced premature senescence). During cellular respiration, molecules with missing or extra electrons – free radicals – are formed in the mitochondria. This is a natural process, which the cell usually regulates with the help of antioxidants – substances that neutralise radicals. But occasionally they manage to escape from the mitochondrion into the cytoplasm or even into the cell nucleus, where they damage macromolecules, including proteins and DNA. The older the cell, the more such damage accumulates in it. DNA repair proteins come into play. When there are enough signals of DNA errors, the repair proteins stop the cell cycle. This is where the free-radical theory of aging comes in. Under the influence of stress factors (starvation, radiation, toxins), the number of radicals increases and oxidative stress develops. If it is strong enough, the cell can age prematurely.

- Oncogene-induced aging. It is believed that cell aging is not only a side effect of accumulating damage, but also a defence mechanism. When a normal cell turns into a cancer cell, the process can still be stopped at the initial stages. As soon as tumour-related genes (e.g. ras) start working actively, the ageing programme starts in parallel. And, if there is no mutation in the genes that stop the cell cycle, it saves the organism from a new tumour. Therefore, premature senescence can be induced in cells by activating ras or other oncogenes in them (see M. Serrano et al., 1997. Oncogenic ras Provokes Premature Cell Senescence Associated with Accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a).

- Programmed senescence (developmental senescence). At certain stages of embryonic development, a part of the cell mass dies off, for example, to form cavities or to remodel tissue. At the same time, the ‘doomed’ cells stop dividing and start the ageing programme. This process depends neither on telomere length nor on the level of stress. It is believed that it evolutionarily preceded stress-induced senescence (see D. Muñoz-Espín et al., 2013. Programmed cell senescence during mammalian embryonic development).

Pic. 2. The need to evolve, DNA damage, and oncogenes cause programmed, stress-induced, and oncogene-induced aging, respectively – in both naked shrews and mice. Image from the PNAS article under discussion.

Until recently, it was only known that naked shrews are not susceptible to replicative senescence. As in other small rodents, telomerase, an enzyme that completes telomeres, works in their cells. In humans telomerase is active only in embryonic and stem cells, in mature cells its gene is switched off. However, even here the mammals have distinguished themselves. Sequencing of their genome showed that the genes encoding their telomerase and related proteins have significant differences from similar genes in other rodents. This suggests that the telomerase of shrews has undergone selection and now probably works more efficiently than in their distant relatives (see The genome of the naked shrew – the key to the secret of longevity?, ‘Elements’, 11.11.2011). As for other mechanisms of cellular aging, nothing was known about them. We can only assume that diggers are less likely to encounter oxidative stress, as they live in narrow underground passages and are less exposed to oxygen and sunlight (the former contributes to the accumulation of radicals in the cell, and the latter contains ultraviolet rays that damage DNA).

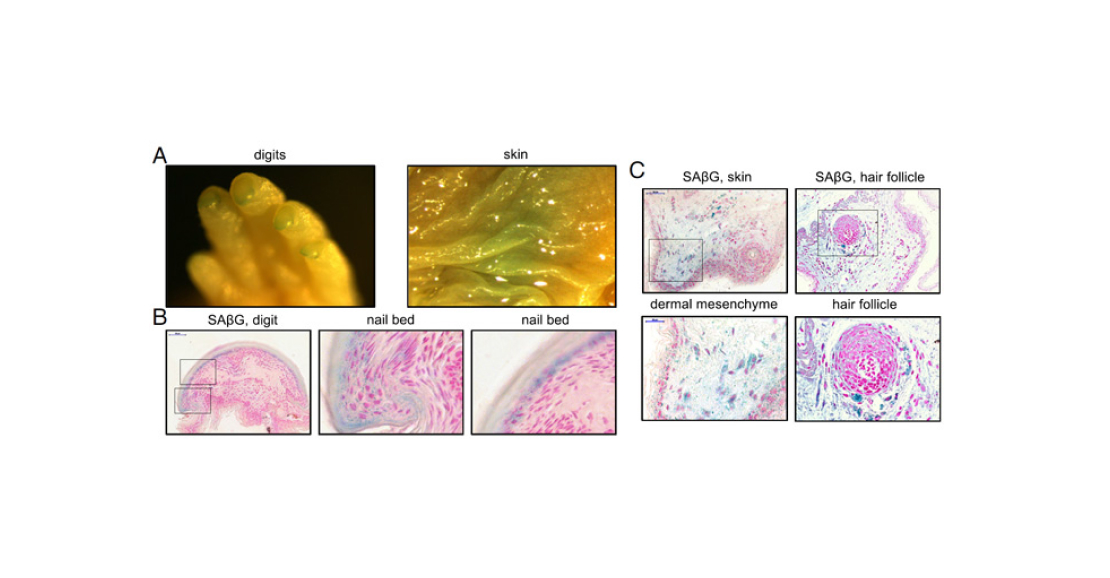

The authors of the paper under discussion carefully screened naked molehills for extant aging mechanisms. The first thing they were interested in was programmed aging, as a more ancient mechanism. To detect it, they stained newborn naked mammals and histological preparations of their organs for β-galactosidase (Figure 3). They were able to detect it not only in areas characteristic of mice – bone marrow and skull – but also in skin and hair follicles. The authors believe that this fact may explain how mammals managed to get rid of their hair cover – with the help of aging and non-dividing cells in follicles.

Pic. 3. Results of β-galactosidase staining. A – fingers and skin of a naked digger. B – finger slice and enlarged images of the nail bed area. C – slice and enlarged images of skin (left) and hair follicle. All images show areas or individual cells coloured blue – this is a sign of old cells. Image from the PNAS article under discussion.

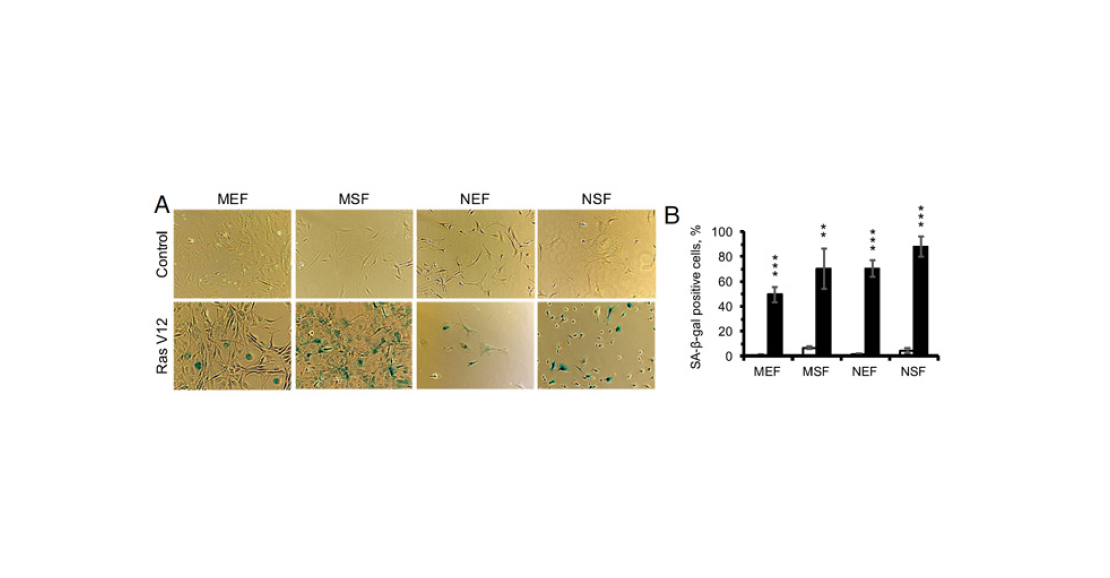

The authors then tried to induce oncogene-induced senescence in a culture of fibroblasts from embryonic tissues and skin of shrews. They activated ras gene expression in the cells, waited 12 days, and then stained again for β-galactosidase (Figure 4). Judging by the number of blue cells in the photographs, this mechanism of aging in shrews is also possible.

Pic. 4. Results of β-galactosidase staining in fibroblast culture. A – microphotographs. Upper row of pictures – control, lower row – cells after 12 days of ras oncogene. B – percentage of positively stained cells. White bars are before exposure, black bars are after. From left to right: mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), mouse skin fibroblasts (MSF), mouse embryonic fibroblasts (NEF), mouse skin fibroblasts (NSF). Image from the discussed article in PNAS.

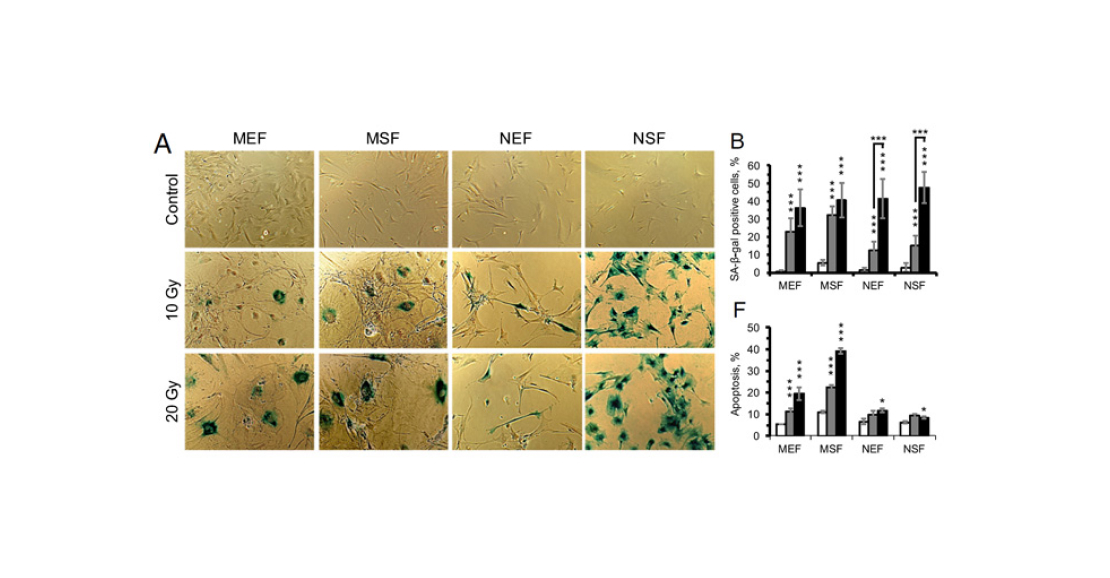

Next in line was stress-induced senescence. The authors of the paper chose gamma radiation as the stressor. They irradiated cells with small (10 Gy]) and stronger (20 Gy) doses and then stained again for β-galactosidase and measured the level of apoptosis (Figure 5). It turned out that naked shrew cells were susceptible to this senescence as well. However, a dose of 10 Gy was not enough to induce a significant response: it took 20 Gy to make the response of mole cells comparable to that of mouse cells at the same dose of irradiation. It is interesting that apoptosis (programmed cell death) was not triggered in shrew cells, while for mouse cells it was a characteristic response to severe stress.

Pic. 5. Experiment on exposure of mouse and naked shrew fibroblasts to gamma radiation. A – results of β-galactosidase staining. Top row of images is control, middle row is irradiation with 10 Gy dose, and bottom row is irradiation with 20 Gy dose. B – percentage of positively stained cells. F – percentage of apoptotic (dying) cells in the culture. White bars – control, grey – 10 Gy dose, black – 20 Gy dose. From left to right: mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), mouse skin fibroblasts (MSF), mouse embryonic fibroblasts (NEF), mouse skin fibroblasts (NSF). Image from the discussed article in PNAS.

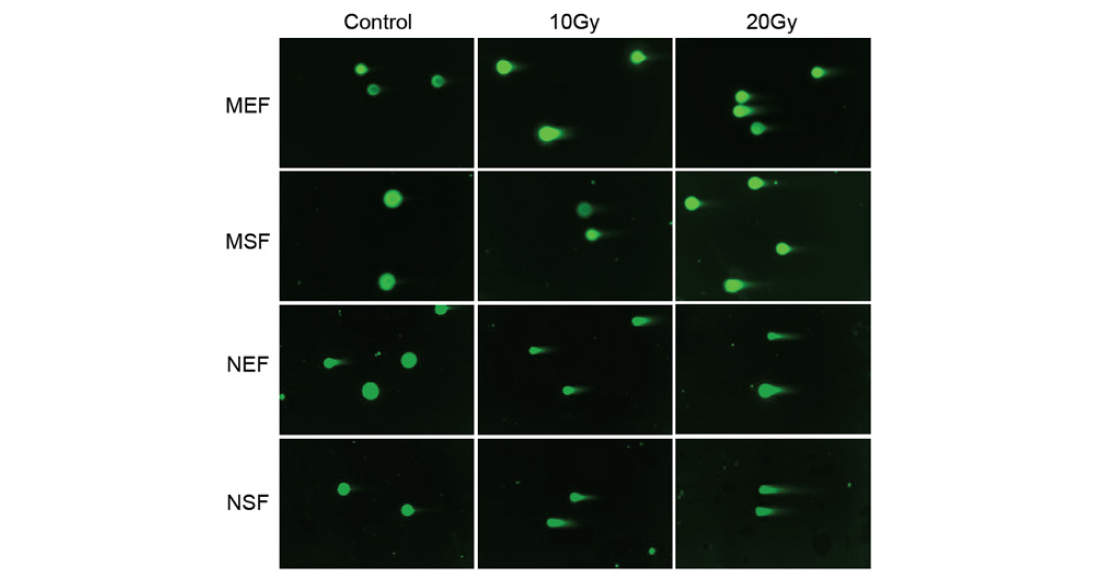

To test whether radiation damages mouse and mammal DNA in the same way, the authors of the paper used the DNA comet method. After radiation, the DNA in the cells is stained and the cell membranes are destroyed. The DNA is then forced to move in an electric field. If the DNA has been damaged by the radiation, breaks are created in the DNA. This produces fragments of different lengths that form a ‘comet tail’ as it moves in the electric field (Figure 6). It turned out that DNA is damaged to the same extent in both molehills and mice. This means that they differ not in the degree of resistance to stress, but in their reaction to it. Both trigger the aging programme, but the cells of mammals, unlike the cells of mice, do not go to programmed death.

Pic. 6. DNA comet method in mouse and naked shrew cells. DNA is coloured in green. From left to right: control, 10 Gy irradiation, 20 Gy irradiation. From top to bottom: mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), mouse skin fibroblasts (MSF), naked mole embryonic fibroblasts (NEF), naked mole skin fibroblasts (NSF). Image from the discussed article in PNAS.

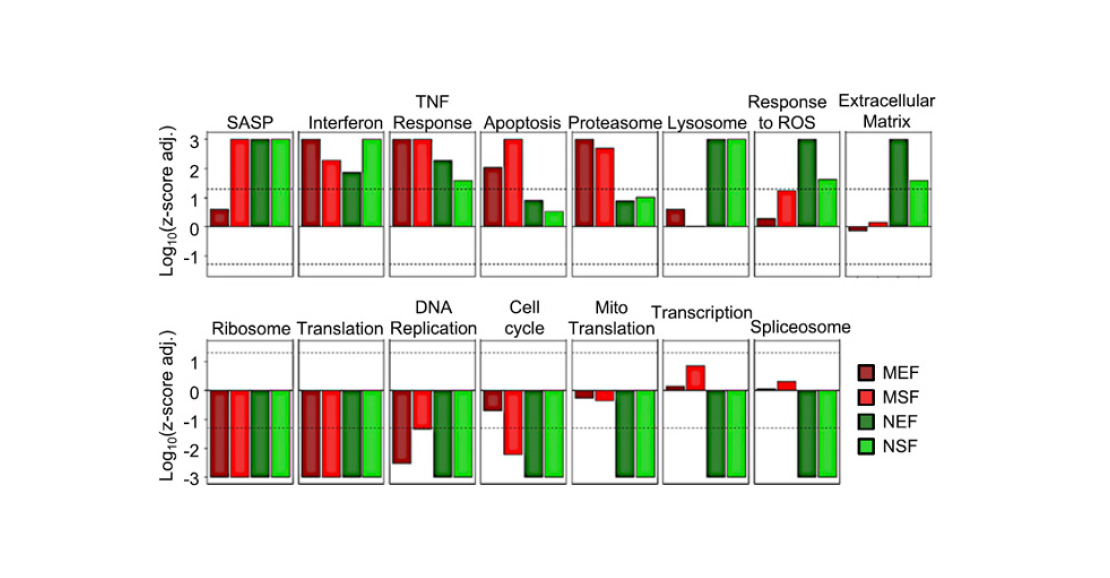

Finally, the authors of the paper analysed how gene expression in cell cultures changes during stress-induced senescence (Figure 7). Here’s what became clear as a result:

- In all cell cultures, the expression of many genes at once is altered. However, in the mouse, the differences between embryonic and adult fibroblasts are stronger than in the earthworm. This is consistent with the notion that shrews hardly ever ‘grow up’.

- SASP genes were activated in all cultures. This can be considered as a second confirmation that cell senescence in naked mammals is possible.

- The set of processes triggered and suppressed under stress differs between mouse and shrew. In contrast to mouse cells, the cells of the shrew do not enter apoptosis, as noted above. Also, genes responsible for cellular protein synthesis are suppressed in them, but genes associated with the stress response (breakdown of substances, antioxidants, etc.) are much more active.

- Finally, the most surprising result is the following: while the number of genes that changed expression in response to radiation was greater in shrews than in mice, the number of processes that changed their activity was smaller. This probably means that the aging process in mammals is more clearly organised – fewer genes are triggered enough to regulate more processes.

Pic. 7. Gene expression after gamma irradiation dose of 20 Gy. Dark red bars represent mouse embryonic fibroblasts, red bars represent mouse dermal fibroblasts, dark green bars represent mouse embryonic fibroblasts, and green bars represent mouse dermal fibroblasts. Image from the discussed article in PNAS.

The authors of the discussed article have shown that three of the four known aging mechanisms are possible in naked mammalian cells. This doesn’t mean that all of them (with the exception of programmed senescence) occur normally. But it does show that, contrary to previous ideas, the aging programme itself has not been lost in naked mammals and they are capable of triggering it. Another thing is that the strategy of behaviour of their cells facing aging is not similar to what we are used to. The cells of naked molehills have a lower overall metabolic rate, so they probably release fewer pro-inflammatory substances and do less damage to the body. At the same time, they have an increased antioxidant response, but do not trigger apoptosis, so the body’s cellular resources are not depleted. Separately, it is worth noting the efficiency of the organisation of the ageing process: fewer genes are activated in the cells of shrews than in mice, but they control a large number of processes. It can be assumed that such an organisation allows, among other things, to keep the cell metabolism at a low level and save resources.

Active research of naked molehills in laboratories began relatively recently, so now for the study are available mainly ‘young’ individuals. The most interesting, apparently, will begin when they grow up to 30 years of age and it will be possible to study the cellular physiology of ‘old’ mammals. That’s when we will find out what happens to the cells of mammals at the end of life and whether they actually work aging programmes.

Author: Polina Loseva, ‘Elements’.

Photo: www.wrs.com.sg

Source

Scientific Journal Elements. Article: Naked mole rats’ cells age differently than mouse cells