Who is to blame: the person or the circumstances?

The human mind strives to understand the meaning of what is happening. If labor productivity decreases, does this mean that workers become more lazy? Maybe the equipment they use has become outdated and less efficient? Is it possible to say that a boy who beats his classmates is aggressive from birth? Or is this how he reacts to endless ridicule? When the seller says, “This thing is just made for you!” – do these words reflect his true feelings? Or is it just a clever move by a “huckster”?

We endlessly analyze and discuss various events and their possible causes, especially if something unpleasant or unexpected happens. It is known, for example, that family people often analyze the behavior of their “halves”, especially their negative actions. The coldness and hostility of one spouse more often than a gentle hug makes the other wonder “Why?”. The explanations they find themselves correlate with their satisfaction with their marriage in general. Dissatisfied with their family life, people usually offer explanations for negative actions that only make the situation worse (“She’s late because she doesn’t give a damn about me at all”). Those who are happily married, as a rule, explain what happened for external reasons (“She was late because there were traffic jams all around”). If the other half does some kind of good deed, the explanations also depend on the nature of the relationship: “He brought me flowers because he wants to sleep with me” or “He brought me flowers to prove his love.”

Antonia Abbey and her colleagues have collected a lot of evidence proving that men, more than women, tend to explain the friendly attitude of women with a certain sexual interest (Abbey et al., 1987; 1991). Such a misconception, expressed in the fact that ordinary friendliness is interpreted as a sexual appeal (it is called erroneous attribution), can contribute to behavior that women (and especially American women) perceive as sexual harassment or attempted rape (Johnson et al., 1991; Pryor et al., 1997; Saal et al., 1989). Such erroneous attribution is especially likely in situations where a man has a certain amount of power. The boss may well misinterpret the friendliness and agreeableness of the woman subordinate to him and, without doubting his correctness, will give all her actions a “sexual coloring” (Bargh & Raymond, 1995).

Such erroneous attributions help explain the increased sexual persistence of men around the world and the growing number of men from different cultures from Boston to Bombay who justify rapists and blame rape on the behavior of their victims (Kanekar & Nazareth, 1988; Muehlenhard, 1988; Shotland, 1989). According to women, men who commit sexual violence are criminals who deserve the most severe punishment (Schutte & Hosch, 1997). Erroneous attributions also help to understand why, at the same time, 23% of American women say that they were forced into sexual relations, while only 3% of men say that they had forced women to do so (Laumann et al., 1994). Sexually aggressive men are particularly prone to misinterpretation of women’s sociability (Malamuth & Brown, 1994). They just “can’t wrap their heads around it.”

Attribution theory analyzes how we explain the behavior of others. Different versions of this theory share some common theoretical principles. Daniel Gilbert and Patrick Malone believe that “for each of us, human skin is a kind of special boundary separating one group of “causal forces” from another. On the sunlit surface layer of the skin (epidermis) there are external or situational forces, the action of which is directed inward at a person, and on the fleshy surface there are internal or personal forces facing outward. Sometimes the action of these forces coincides, sometimes they act in different directions, and their dynamic interaction manifests itself in the form of the behavior we observe” (Gilbert & Malone, 1995).

Fritz Haider, the widely recognized creator of attribution theory, analyzed the “psychology of common sense” that people use to explain everyday events (Hider, 1958). The conclusion he came to is as follows: people tend to attribute the behavior of others either to internal reasons (for example, personal predisposition), or to external ones (for example, the situation in which the person found himself). Thus, a teacher may doubt the true causes of his student’s poor academic performance, not knowing whether it is due to a lack of motivation and abilities (“dispositional attribution”) or a consequence of physical and social circumstances (“situational attribution”).

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Published

July, 2024

Duration of reading

About 3-4 minutes

Category

Social Psychology

Share

(— So, if the coffee is good, then the thanks will be to Mr. Coffee, and if it is bad, then the complaints will be to me.) We tend to explain the behavior of others or the results of certain events either by internal (dispositional) or external (situational) reasons.

It is often not possible to draw a clear line between internal (dispositional) and external (situational) causes, because external circumstances cause internal changes (White, 1991). Perhaps there is only a small semantic difference between the expressions “A schoolboy is scared” and “School scares a child”, nevertheless, social psychologists have found that we often attribute the behavior of others or solely to their dispositions [Dispositions are stable traits, motives and attitudes inherent in a personality. — Notable scientific ed.], or only situations. So, when Konstantin Sedikidis and Craig Anderson asked American students why Americans were opposed to the Soviet Union, 8 out of 10 respondents explained this by saying that Americans considered its citizens “deluded,” “ungrateful,” and “prone to betrayal.” However, 9 out of 10 respondents considered all the shortcomings of Russians to be a consequence of the repressive regime prevailing in their country (Sedikides & Anderson, 1992).

Alleged features

Edward Jones and Kate Davis drew attention to the fact that we often assume that the intentions and dispositions of others correspond to their behavior (Jones & Davis, 1965). If Rick makes a sarcastic remark about Linda in my presence, I can assume that he is an unkind person. The “Theory of Relevant Assumptions” created by Jones and Davis specifies the conditions under which such attributions are most likely. For example, ordinary or expected behavior tells us less about a person than unusual behavior. If Samantha allows herself to be sarcastic during an interview, the outcome of which depends on whether she will be hired or not (i.e., a situation in which it is customary to behave politely), this tells us more about her than her sarcasm towards friends.

The ease with which we attribute certain qualities to people is admirable. James Ullman, conducting experiments at New York University, asked students to memorize various phrases, including the following: “A librarian carries an elderly lady’s purchases across the street.” At the same time, students immediately, against their own will and subconsciously, made a conclusion about personal quality. When the experimenter later helped them remember this sentence, the most valuable keyword was not the word “books” (a hint related to the librarian) or the word “bags” (a hint about shopping), but “inclined to help” — a supposed trait that, it seems to me, you also involuntarily attributed to the librarian.

Common sense attribution

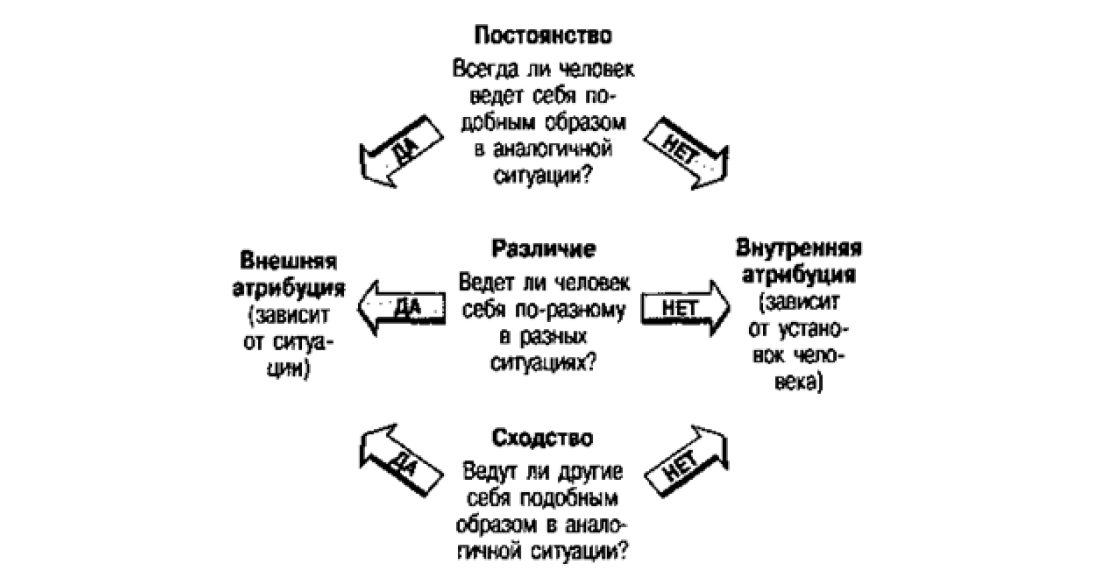

As these examples show, attributions are often rational. As proof of the rationality of the ways we interpret behavior, attribution theorist Harold Kelly described our use of information about “consistency,” “differences,” and “consensus” (Kelley, 1973) (Figure 3.1). Trying to understand why Edgar has problems with his XYZ computer, most people, as expected, they use information about consistency (does Edgar’s computer always malfunction?), about differences (does Edgar have problems when he works on all computers, or only on XYZ?)and about consensus (do other XYZ computer users have the same problems as Edgar?).

3.1. Harold Kelly’s theory of attribution.

Whether we explain someone’s behavior by internal or external reasons depends on three factors: consistency, differences, and consensus. Try to come up with your own examples of such a plan: if Mary and many others criticize Steve (consensus) and if Mary does not criticize anyone else (high level of difference), we conclude that there is some external reason (i.e. Steve really deserves criticism). If Mary is the only one who criticizes Steve (low consensus) and if she criticizes many others as well (low difference), we resort to internal attribution (the reason is Mary herself).

So, at the level of common sense, we often explain behavior logically. However, Kelly found that in everyday life, people often underestimate other possible causes if other plausible explanations for a particular behavior are known. If I am able to name one or two reliable reasons why a student might have failed the exam, then I may well ignore or underestimate alternative explanations (McClure, 1998).

Information integration

Additional evidence in favor of the reasonableness of our social judgments is obtained by studying the integration of information. According to Norman Anderson and his colleagues, there are certain rules by which we create a holistic impression of a person based on disparate information (Anderson, 1968; 1974). Let’s say you’re going to meet a girl you don’t know who you’ve been told is “smart, fearless, lazy, and sincere.” The results of studying how people relate such information suggest that you are likely to “weigh” each of these definitions in terms of their significance to you. If you consider sincerity to be the most important quality, you will attach more importance to it; it is also likely that you will be more sensitive to negative information. Such negative information as “she is a dishonest person” may turn out to be the most “powerful” factor due to its unconventionality. If you are like the participants in the experiments of Solomon Asch (1946), Bert Hodges (1974), Roos Wonka (1993), and Ramadhar Sinha and his colleagues (Singh et al., 1997), you can overestimate the information that you receive before others, i.e. demonstrate a phenomenon called the “primacy effect.”The first impression can influence the interpretation of the information that you receive later. After someone tells you that they are “smart,” you may interpret that person’s determination as bravery rather than recklessness. After weighing and interpreting all the information you receive, your “internal calculator” will come into play and the integration of individual information will take place. The result will be a general impression of the stranger you are about to meet.

Source: Myers D. “Social Psychology”

Photo: www.myk104.com

Source

Article from NICE VT