The cures for aging, and where they reside

Time does not directly kill people, aging is a biological process. There are diseases that are called age-associated or senile diseases. The main risk factor for their development is age, and they account for a significant share among the causes of mortality. These are strokes, heart attacks, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, type 2 diabetes….. These are the diseases that are killing us. Scientists working in the biology of ageing are looking for what they have in common, a single mechanism, if, of course, it exists.

I would like to talk about whether there are actually any advances in the ‘heroic’ fight against aging. From time to time we are told by the media that scientists have discovered the aging gene, but there are still no anti-aging pills in pharmacies. I would like to know how things really are. To do this, we need to define what we consider success in the fight against aging. Do we want people to live to be a hundred years old? Or a hundred and fifty? Then we can talk about success or not yet?

We must realise that the biology of ageing is a very hype topic, and it is a double-edged blade, because any talk on this topic is easy to sell both literally and figuratively. This subject requires from scientists, on the one hand, correctness and restrained optimism, and on the other hand, the ability not to go to extremes in their ideas. There are two opposing views. One is that nothing can be done about ageing at all: as it is written in the genes, so it will be. The other one implies that immortality should come literally in a few days. The latter is used by some pharmacological companies, which start selling jars with ‘cure for old age’. But if somewhere in secret laboratories there was a jar with such a medicine, we would already live in another world.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Where are ‘cures for old age’ being sought

One of the obvious directions in the search for anti-ageing remedies is to replace organs that decay in the ageing process with new, specially grown organs. It is now more or less clear in which direction to move in order to achieve this. There are techniques that allow reprogramming specialised, terminally differentiated cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can then be transformed into almost all types of cells. It is possible to take from an elderly patient his own cells, turn them into iPSCs, in the course of which they, among other things, lose features characteristic of senile cells (sometimes the term ‘rejuvenate’ is used, but it is recommended to avoid it). Then it is possible to grow a ‘young’ organ or at least a ‘young’ tissue from them and transplant it to the patient.

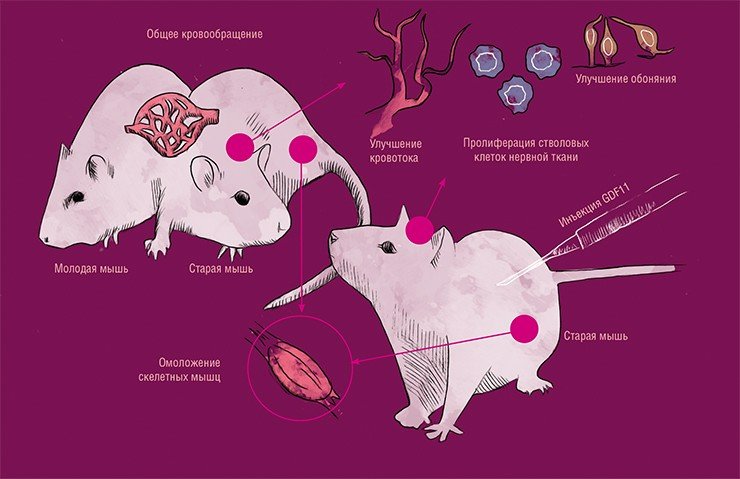

The surgical creation of a common blood circulation between laboratory mice of different ages, as well as injections of GDF11 protein derived from the blood of young mice into the elderly mice, led to the same result: signs of aging of the muscular, nervous and circulatory systems were reduced in the ‘elderly’ mice.

One of the problems with the method is that it is a tactical retreat that makes sense only until the brain is involved: it cannot be replaced so easily. The second problem is that cells with the properties of young cells, when surrounded by senescent cells, acquire the phenotype (molecular markers) of senescent cells (Acosta et al., 2013). Thus, a young organ grown and transplanted will not stay young for long.

However, this effect works in the opposite direction: old cells, once among young cells, acquire their properties! To understand how this happens and possibly to reproduce this effect, it is necessary to find a molecular substrate of ‘recognition’ by cells of ‘young’ or ‘old’ cellular environment. This substrate is probably some signalling molecules. The results of experiments using parabiosis, artificial connection of mice through the blood system, as a result of which muscle and nerve tissues of old mice ‘rejuvenated’, revealed and the supposed candidate for the mediator of this effect. It turned out to be the GDF11 protein (growth and differentiation factor 11) isolated from the blood of young mice (Sinha et al., 2014). It is true that these works were later criticised, which consisted in the fact that GDF11 is a concomitant finding, and therefore the research is still ongoing (Reardon, 2015). But I believe it is only a matter of time before the true mediator or mediators are discovered.

Another strategic direction to combat aging is to try to influence its mechanisms directly by altering the regulation of nutrient and energy metabolism. The substrates of influence include growth hormone, which controls tissue growth, and insulin-like growth factor, a molecule similar to the hormone insulin, which is necessary for the regulation of glucose metabolism but has a wide range of actions on the processes of cell growth and development.

The molecular systems in question ‘make decisions’ about how actively cells should grow, divide, and utilise energy. And, although it seems non-obvious, during aging such systems begin to work harder, not weaker, but more inefficiently (Blagosklonny, 2010). As a result, most potential agents that alter the functioning of these systems are aimed at suppressing them. For example, these include the antibiotic and immunosuppressant rapamycin, which inhibits the so-called mTOR kinase signalling pathway, involved in synthetic processes in the cell and activated by amino acids. Rapamycin has serious side effects and is not suitable for use in prolonging human life, but perhaps more suitable substances will be found in the future. One of them may be the anti-diabetic drug metformin, if it is proved to be safe to use for preventive purposes.

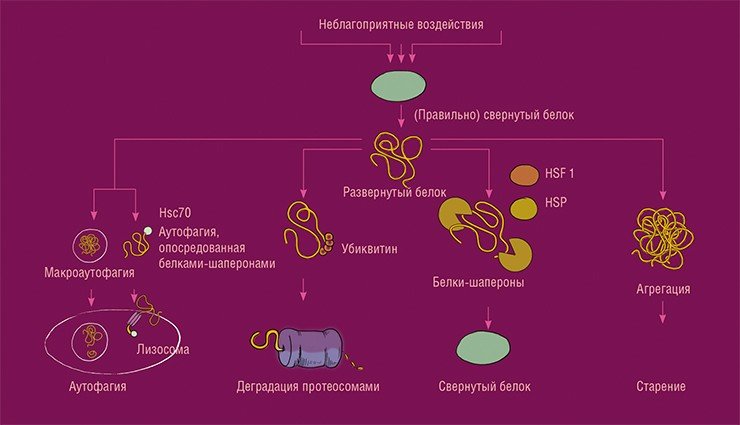

It should be noted that the aging process is very slow for quite a long time and then accelerates. The point is that there are ‘quality control systems’ in the body that are busy ‘fixing what is broken’ and what cannot be fixed is sent for recycling. These include, for example, the proteostasis system, which is responsible for the proper clotting of protein molecules; and the autophagy process, which is, among other things, an important link in sending damaged cell organelles for recycling; and apoptosis (cellular ‘suicide’). Finally, the immune system itself, which fights not only infections but also tumour cells. Over time, all these systems begin to work worse, but if you return them to their former activity, it may be possible to reverse a number of ageing changes, and one of the directions of work is just looking for substances that would increase the activity of ‘quality control systems’.

Another direction is related to the fact that in the course of aging in the tissues of the body develops a state of weak, sluggish, unable to complete inflammation – the so-called smouldering inflammation (Salminen, Kaarniranta, Kauppinen, 2012). Generally, inflammation is characterised by five signs: redness, swelling, pain, fever and impaired function. And perhaps if we fight inflammation or what causes it during aging, we can restore lost functionality to tissues.

The proteostasis system is one of the ‘quality control systems’ functioning in cells. Under the influence of a number of unfavourable factors, such as oxidative stress, proteins can lose their structure, the complex coiling of the protein molecule. Such proteins must either be destroyed – through the process of autophagy or ubiquitin-proteosome system, or their structure can be restored with the participation of chaperone proteins. Otherwise, they will form aggregates, the accumulation of which leads to cell dysfunction and aging. Autophagy is subdivided into micro- and macroautophagy. The first type is called chaperone-mediated autophagy, where these proteins are involved in channelling damaged protein to the lysosome, a cell organelle containing enzymes for the cleavage of cellular macromolecules. Macroautophagy is associated with the formation of a membrane structure, the autophagosome, which contains the protein to be destroyed and, by fusing with the lysosome, ensures its degradation. From: (Lopez-Otín et al, 2013)

It has been known for quite a long time (although it took a long time to confirm this phenomenon) that caloric restriction leads to slower development of senile changes and increased longevity (Colman et al., 2009). In rats, an increase in longevity of up to 40% was achieved in this way. These experiments prove that artificial increase of maximum life expectancy is possible in principle. Caloric restriction also affects quality control systems and reduces smouldering inflammation, i.e. it seems to ‘hit’ very close to the subject of the search – the general mechanism of ageing.

Problems and solutions

I have described the areas of aging biology in which research is actively underway, but any such list would be obviously incomplete. Many processes that are disturbed during aging are already known, and, importantly, hundreds of candidate substances are known as potential ‘anti-aging drugs’ – geroprotectors. The abundance of potential targets and techniques, on the one hand, is gratifying, because it indicates that the stage of searching for any targets has been passed. But another problem has arisen: now there are many more potential targets than the scientific community can ‘digest’. Perhaps among several hundred potential geroprotectors there is the most effective one, but how to identify it? The number of laboratories and specialists becomes a limiting factor.

What can be the way out of this situation? One is to involve non-specialists, similar to what ornithologists do: they accept observations from people who are members of birdwatching communities (this approach is called ‘citizen science’). Aging experts propose to involve dog owners in their work (Kaeberlein, 2016). The dog is one of the very few animal species whose accumulated medical data is comparable to that of ‘human’ medicine. Dog owners receiving experimental treatments for their pets could collect data (simple, at-home measures) and send reports on the results.

Another possible option for activating data collection can be mentioned, although it is debatable. Under a recent law introduced in many US states, a terminally ill person is entitled to receive experimental treatments, if they exist, without waiting for the end of the approval process. Some such patients feel they have nothing to lose and do so at their own risk. This is a very specific case, though, and even it remains an ‘arena’ of heated debate, so people should not be actively encouraged to use deeply experimental techniques.

It is very difficult to study the aging process on humans. A person ages for a long time, it is inconvenient from the methodological point of view. One should not forget about ethical aspects. That is why aging is mainly studied on nematode worms, yeast, flies, mice – on short-lived organisms. Studies on model organisms are a good approach, but humans are neither mouse nor fly, and not everything that is true for models will also be true for humans (de Magalhães, Stevens, Thornton, 2017). Several hundred genes are known in yeast and nematodes whose function is associated with aging, but in humans these genes are largely dysfunctional or absent.

According to the GenAge database, several hundred genes are known for yeast and nematodes, the function of which is associated with aging. However, these data are overwhelmingly inapplicable to humans, for whom only 7 such genes are known. From: (de Magalhães, Stevens, Thornton, 2017)

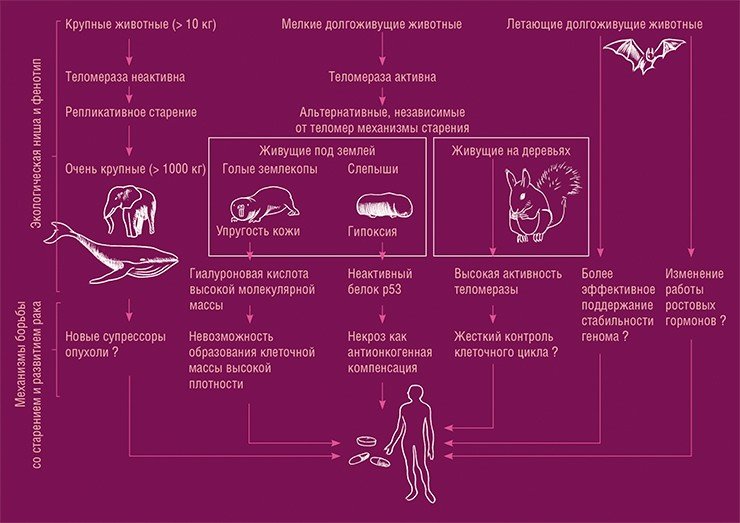

One way to get around this problem is to ‘fit the solution to the answer’. There are animals that have overcome the aging problem and live long lives: longevity correlates well with organism size, but some animals break out of this pattern. These include rodents – naked shrews and gadflies, some bats, birds, and very large mammals. It is possible to study how they differ from non-long-lived organisms and to try to mimic with pharmacological agents the action of gene variants responsible for long life (Gorbunova et al., 2014).

Experiments that ‘ran themselves’ can also be found in human populations. Today, there are ongoing studies of the genomes of people who have lived more than 100 years (Puca et al., 2017), with the consideration that these people have ‘won the genetic lottery’. And the identification of gene variants (alleles) associated with their longevity can tell us which substances can reproduce this effect in the general population.

Some small animals (rodents, bats, squirrels) have managed to overcome the problem of ageing as well as the development of cancer, as have very large animals like elephants. Different species use different molecular mechanisms to do this. For example, in naked shrews, cells cannot be arranged as tightly together as they are in the early stages of cancerous tumour development. The defence systems of gadflies use ‘scorched earth’ tactics in relation to cancer, killing not only the cancer cell, but also all its surroundings, among which there may be potentially dangerous cells. Having studied these mechanisms, we can try to mimic them with pharmacological methods and apply them to humans. From: (Gorbunova et. al., 2014)

Some potential geroprotectors are drugs that have long been used in medicine (e.g., metformin mentioned above), and the study of the course of aging diseases in people taking them for extrinsic indications may help us to identify the most promising substances.

A promising direction is the search for biomarkers of aging – indicators whose rate of change over a relatively small period of time, such as a year, fairly reliably reflects the overall speed of this process (Sprott, 2010). The use of biomarkers will allow direct investigation of the efficacy of geroprotectors without requiring lifelong follow-up.

And on to the future of anti-aging. Let me first give the statistics on survival rates for patients with cancer as an example. Although it still seems to us that cancer is a verdict, for many types of tumours the figures for survival and long-term remission have increased by tens of percent, for example, for prostate cancer – from 30% to 70%. Basic research has been going on for a long time, and now we are seeing the fruits of work that began in the mid-20th century. It is likely that the results of the fight against ageing will be the same ‘quiet revolution’. We will not wake up and read in the headlines that ageing has been defeated. It will be a gradual process preceded by a gradual accumulation of new data. First we will learn that life extension is possible in principle, then we will discover more and more geroprotectors that work, then life expectancy will start to rise… And one day we will look back and see that progress is indeed being made.

Literature

Blagosklonny M. V. Calorie restriction: decelerating mTOR-driven aging from cells to organisms (including humans) // Cell Cycle. 2010. V. 9. N. 4. P. 683-688.

Colman R. J., Anderson R. M., Johnson S. C. et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys // Science. 2009. V. 325. N. 5937. P. 201-204.

de Magalhães J. P., Stevens M., Thornton D. The business of anti-aging science // Trends in biotechnology. 2017. V. 35. N. 11. P. 1062-1073.

Gorbunova V., Seluanov A., Zhang Z. et al. Comparative genetics of longevity and cancer: insights from long-lived rodents // Nat Rev Genet. 2014. V. 15. N. 8. P. 531-540.

Puca A. A., Spinelli C., Accardi G. et al. Centenarians as a model to discover genetic and epigenetic signatures of healthy ageing // Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2017. doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2017.10.004.

Sinha M., Jang Y. C., Oh J. et al. Restoring systemic GDF11 levels reverses age-related dysfunction in mouse skeletal muscle // Science. 2014. V. 344. N. 6184. P. 649-652.

Sprott R. L. Biomarkers of aging and disease: introduction and definitions // Experimental gerontology. 2010. V. 45. N. 1. P. 2-4.

Published

June, 2024

Duration of reading

About 3-4 minutes

Category

Aging and youth

Share