A new twist in the quantum theory of the brain

A new theory explains how fragile quantum states can persist for hours and even days in our warm and moist brains. Experiments are already being prepared to test it.

The mere mention of “quantum consciousness” causes most physicists discomfort, as this phrase seems to remind them of the mutterings of some New Age guru. But if the new hypothesis is confirmed, it will turn out that quantum effects do play a role in human consciousness. Matthew Fisher, a physicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, surprised many last year by publishing a paper in the Annals of Physics suggesting that the nuclear spins of phosphorus atoms could serve as rudimentary qubits of the brain, which is why it is able to work on the principle of a quantum computer.

Even 10 years ago, this hypothesis would have been rejected as nonsense. Physicists have already stepped on such a rake, especially in 1989, when Roger Penrose suggested that mysterious protein structures, “microtubules,” play a role in shaping consciousness using quantum effects. Few people believed in the reliability of such a hypothesis. Patricia Churchland, a neurophilosophist from the University of California, commented on this topic that to explain consciousness, one might as well talk about “fairy dust in synapses.”

Fischer’s hypothesis has the same difficulties as microtubules: quantum decoherence. To build a working quantum computer, it is necessary to combine qubits – quantum bits of information – to bring them into an entangled state. But entangled qubits are very fragile. They must be carefully protected from any noise in the environment. A single photon colliding with a qubit will disrupt the coherence of the entire system, destroy entanglement, and destroy the quantum properties of the system. Quantum processing is difficult to carry out in carefully controlled laboratory conditions, not to mention the warm, moist and complex mess of human biology, in which maintaining coherence for a long time is almost impossible.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Published

June, 2024

Duration of reading

About 5-6 minutes

Category

The brain and nervous system

Share

Matthew Fisher, who proposed a theory about the effect of quantum effects on brain function

But over the past decade, there has been increasing evidence that some biological systems can work with quantum mechanics. For example, during photosynthesis, quantum effects help plants convert sunlight into fuel. Scientists also suggest that migratory birds have a “quantum compass” that allows them to use the earth’s magnetic field for navigation, and that the sense of smell is also rooted in quantum mechanics.

Fischer’s idea of quantum data processing in the brain fits into the new scientific field of quantum biology. Call it quantum neuroscience. He has developed a complex hypothesis involving nuclear and quantum physics, organic chemistry, neurobiology, and biology. And although his ideas face a high level of understandable skepticism, some researchers pay attention to them. “People who have read his work (and I hope there will be more) cannot help but come to the conclusion that the old man is not so crazy,” wrote John Preskill, a physicist at the California Institute of Technology after Fischer gave a talk there. “He may have found something. To say the least, it raises very interesting questions.”

Senthil Todadri, a physicist at MIT and a longtime friend and colleague of Fischer, remains skeptical, but believes that Fischer has changed the main question – whether quantum computing is happening in the brain – in such a way that it is possible to thoroughly test this hypothesis. “It’s generally assumed that, of course, quantum computing in the brain is out of the question,” says Todadri. – He claims that there is exactly one loophole in this regard. So the next step will be to check the possibility of closing this loophole.” Indeed, Fischer is already recruiting a team to conduct laboratory tests that will answer this question once and for all.

In search of spin

Fischer belongs to a dynasty of physicists. His father, Michael I. Fisher, is a renowned physicist at the University of Maryland, whose work in statistical physics has earned him numerous awards. His brother, Daniel Fisher, is an applied physicist at Stanford University specializing in evolutionary dynamics. Matthew Fisher followed in their footsteps, building a very successful career as a physicist. In 2015, he received the prestigious Oliver I. Buckley Award for his research on quantum phase transitions.

So what made him move away from conventional physics towards a controversial and confusing mess of biology, chemistry, neuroscience and quantum physics? His struggle with clinical depression.

Fischer remembers well the day in February 1986 when he woke up feeling unwell and feeling like he hadn’t slept in a week. “I felt like I was drugged,” he said. Sleep didn’t help. A change in diet and exercise yielded nothing, and blood tests revealed no abnormalities. But his condition persisted for two whole years. “It was like a headache all over my body, every waking moment,” he says. He even tried to commit suicide, but the birth of his first daughter gave meaning to his continued struggle with the fog of depression.

He eventually found a psychiatrist who prescribed him tricyclic antidepressant medication, and after three weeks his condition began to improve. “The metaphorical fog that surrounded me and obscured the sun began to thin out, and I saw that there was light behind it,” says Fisher. Five months later, he felt like he had been reborn, despite the serious side effects of the medication, including excessive blood pressure. Later, he switched to fluoxetine and has been constantly monitoring and adjusting his medication regimen ever since.

His experience has convinced him of the effectiveness of medicines. But Fischer was surprised by how little neuroscientists know about the exact mechanisms of their work. This piqued his curiosity, and thanks to his experience in quantum mechanics, he began to consider the possibility of quantum data processing in the brain. Five years ago, he began to study the issue in depth, based on his own experience of taking antidepressants.

Since almost all drugs used in psychiatry usually turn out to be complex molecules, he focused on one of the simplest, lithium, a single atom – a spherical cone, so to speak, which is much easier to study than fluoxetine. By the way, this analogy, according to Fischer, is quite suitable for this case, since the lithium atom is a sphere of electrons surrounding the nucleus. He focused on the fact that you can usually buy the common isotope lithium-7 with a prescription at a pharmacy. But will using a rarer isotope, lithium-6, lead to the same result? In theory, it should, because these isotopes are chemically identical. They differ only in the number of neutrons in the nucleus.

After rummaging through the literature, Fischer discovered that experiments comparing lithium-6 and lithium-7 had already been conducted. In 1986, scientists at Cornell University studied the effect these two isotopes have on the behavior of rats. Pregnant rats were divided into three groups – one was given lithium-7, one lithium–6, and the third served as a control group. After the birth of offspring, the rats treated with lithium-6 had a much stronger maternal instinct, which was expressed in caring, caring, and building nests than in the other two groups.

This startled Fischer. Chemically, the two isotopes should be identical, and even more so they should not show any differences in the moisture-filled environment of the human body. So what could be the reason for the differences in behavior observed by the researchers?

Fischer believes that the secret may lie in the spin of the nucleus, a quantum property that affects how long each atom can remain coherent – isolated from its surroundings. The smaller the spin, the less the core interacts with electric and magnetic fields, and the slower coherence is lost.

Since lithium-7 and lithium-6 have different numbers of neutrons, their spins are also different. As a result, lithium-7 loses coherence too quickly for quantum consciousness to work, and lithium-6 can remain entangled for longer.

Fischer discovered two substances that are similar in everything except quantum spin, and found that they have different effects on behavior. For him, it was a tantalizing hint that quantum data processing plays some kind of functional role in consciousness.

Quantum protection scheme

However, the task of moving from an interesting hypothesis to a real demonstration that quantum processes play a role in brain function looks depressing. The brain needs some kind of long-term storage mechanism for quantum information in qubits. It is necessary to entangle many qubits, and this entanglement in some chemical way must affect how neurons work. There should also be a mechanism for transmitting quantum information stored in qubits throughout the brain.

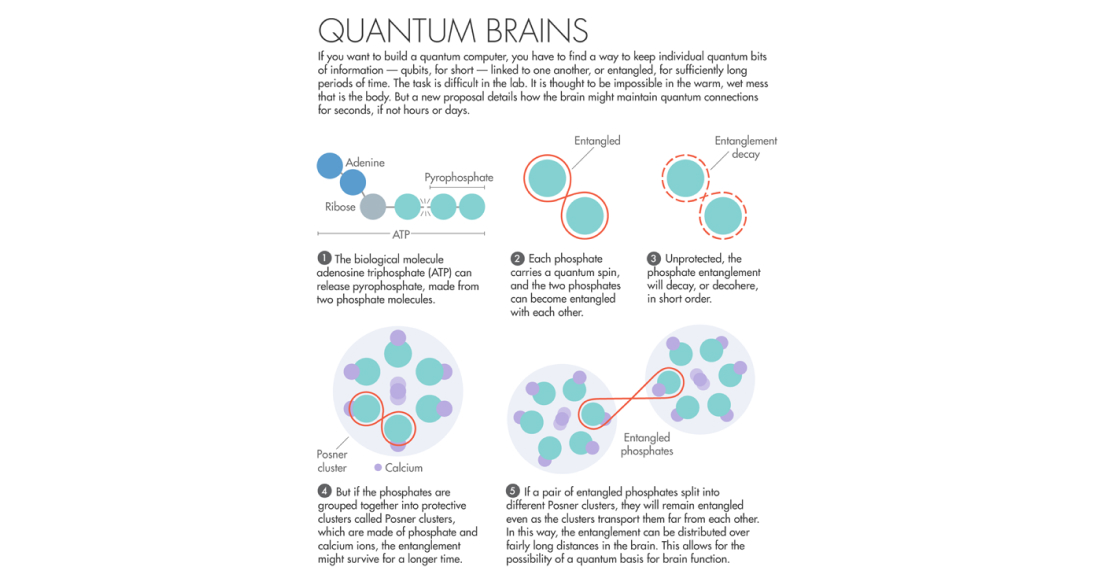

This is a very difficult task. In five years of searching, Fischer identified only one suitable candidate for storing quantum information in the brain: phosphorus atoms, the only common biological element other than hydrogen, with a half spin small enough to increase coherence time. Phosphorus cannot create stable qubits by itself, but its coherence time can be extended if it is combined with calcium ions to form clusters.

In 1975, Aaron Posner, a scientist at Cornell University, discovered an incomprehensible clustering of calcium and phosphorus while studying bone X-rays. He drew the structure of these clusters – nine calcium atoms and six phosphorus atoms, and later they were called “Posner molecules” in his honor. These clusters reasserted themselves in the 2000s, when scientists, simulating bone growth in an artificial liquid, noticed them floating in it. Subsequent experiments have found evidence of their presence in the body. Fischer believes that Posner molecules can serve as a natural qubit of the brain.

That’s the big picture, but the devil is in the little things that Fischer has been studying for the last few years. The process begins in the cell with a chemical called pyrophosphate. It consists of two bound phosphates, each consisting of a phosphorus atom surrounded by several zero-spin oxygen atoms. The interaction between the phosphate spins entangles them. They can create pairs in four different ways: three configurations give a total spin of 1 (loosely coupled triplet), and the fourth gives a zero spin, or “singlet”, a state of maximum entanglement, critically important for quantum mechanics.

Next, the enzymes separate the entangled phosphates into three free ions. They remain entangled even after separation. This process, according to Fischer, is faster for singletons. These ions, in turn, can combine with calcium ions and oxygen atoms and turn into Posner molecules. Calcium and oxygen do not have a core spin, so the total half-integer spin, which is critical for long-term coherence, remains. These clusters protect entangled pairs from external influences so that they can maintain coherence for as long as possible. Fischer estimates that it could be hours, days, or even weeks.

Thus, entanglement can spread over quite large distances inside the brain, affecting the output of neurotransmitters and the functioning of synapses between neurons – a frightening long-range effect in the version of the brain at work.

Theory check

Researchers in the field of quantum biology are intrigued by Fischer’s suggestion. Alexandra Olaya-Castro, a physicist at University College London who has worked on quantum photosynthesis, calls this “a well-thought-out hypothesis. It does not provide answers, but only opens up questions that can lead us to test individual steps of the hypothesis.”

Peter Hore, a chemist at Oxford University, agrees with her. Peter Hore, who studies quantum effects applied to the navigation of migratory birds. “The theoretical physicist offers us certain molecules, mechanisms, and the whole technology of how they can affect brain function,” he says. “This opens up opportunities for experimental testing.”

Fischer is currently trying to conduct experimental tests. He spent a sabbatical at Stanford working with researchers on reproducing a 1986 study with pregnant rats. He admitted that the preliminary results were disappointing, the data did not provide enough information. But he believes that if the 1986 experiment is better reproduced, the results may be more convincing.

Fischer has applied for a grant to conduct deeper experiments in quantum chemistry. He gathered a small group of scientists from various fields at his university and attracted scientists from the University of California, San Francisco. First, he wants to figure out whether calcium phosphate forms stable Posner molecules, and whether the nuclear spins of phosphorus from these molecules can become entangled for long periods of time.

Even Hour and Olaya-Castro are skeptical about this, especially Fischer’s estimates of a day or more. “To be honest, I think it’s highly unlikely,” Olaya-Castro says. “The longest time intervals related to biochemistry that occur in the brain are no more than a second.” (In neurons, information is stored for microseconds). Hour calls this a “remote” possibility, talking about seconds at most. “This doesn’t negate the whole idea, but it seems to me that other molecules will be needed for long-term entanglement,” he says. – I don’t think these are Posner molecules. But I’m interested in how the idea will develop.”

Some people believe that no quantum processes are needed at all for the brain to work. “Evidence is emerging that everything interesting about consciousness can be explained by the interaction of neurons,” Paul Thagard, a neurophilosophist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, told New Scientist.

Many other aspects of Fischer’s hypothesis also need to be properly tested. He hopes that he will be able to set up the necessary experiments for this. Is the structure of the Posner molecule symmetrical? How isolated are the nuclear spins?

More importantly, what if these experiments prove that the hypothesis is incorrect? Then we may have to completely abandon the idea of quantum consciousness. “I believe that if the nuclear spin of phosphorus is not used in quantum data processing, then quantum mechanics does not play a role at all in the work of consciousness over long periods,” says Fisher. — From a scientific point of view, it is very important to exclude this. It will be useful for science to know this.”

Author: Jennifer Ouellette.

Source

Journal Sudonull. Article: A new twist on quantum brain theory