Psychology has long been trying to answer the question of what consciousness is. Cognitive psychologists, once again finding it impossible to answer this question, tried to go from the opposite side, namely, to understand what is possible in our cognition without the participation of consciousness, what can be processed and used beyond it. They even started talking about the so-called cognitive unconscious. But the term “unconscious processes in cognition” is closer to me, because the term “unconscious” is quite closely related to Freud and his psychoanalysis.

If we ask ourselves what is possible in our cognition, in our psyche, without the participation of consciousness, taking as a basis the simplest linear scheme of information processing with input, output and intermediate stages of processing, we can see that in fact we are not aware, but anything can influence behavior. The information we perceive may not be realized. The most famous anecdotal example is the so—called 25th frame. Why is it anecdotal? Because James Vicari, who conducted the famous experiment with the presentation of slides “Eat popcorn and drink Coca-Cola” while watching movies, admitted that he falsified the results of his experiment. Nevertheless, this does not negate the fact that we may not see, hear, or notice certain information due to its too brief or disguised presentation, which will further affect how we interpret other information, for example.

Let’s say if we are briefly shown a word, for example, the word “tiger”, then in half a second we will recognize the word “stripes” faster than “TV”, because the word “stripes” is associated with the word “tiger”, which we have not seen, and the word “TV” is not connected. This phenomenon is called the priming effect. In fact, there are a great many priming effects in human cognition, and the unconscious semantic priming effect is just one of many examples. On the other hand, we may not be aware of our own response to this or that perceived impact. All lie detectors are based on this principle. For example, we are asked to press a button in response to the words that the experimenter tells us. If he says some word that hooks us personally, then in the case of, for example, polygraph testing, we can find out that we are lying. We don’t realize that we are pressing the button a little harder than in response to other words, or that our hand is shaking a little, because if we were aware, we could control it.

The most interesting thing is that we may not realize the connection between the perceived impact and the perceived response. The most famous example here is a study by American cognitive psychologists Richard Nisbett and Timothy Wilson, published under the high—profile title “We Say more than we Know.” Their experiments were very simple. For example, they would come to a large department store and ask naive customers to choose one of the four pairs of gloves that were laid out in front of them, and justify their choice as to why they liked this particular pair and not the other. It is clear that all the pairs were absolutely identical.

Naturally, they were laid out in front of customers in different order to avoid various external factors. They found that the choice was significantly influenced by only one single factor, namely the location of a pair of gloves in a row. Most of the customers preferred the first pair. Let me remind you, she was the same as the others. It could have been any of the four pairs of gloves used in the experiment. At the same time, none of the customers indicated the order of presentation of gloves as a factor that could influence her choice. They gave absolutely any explanation except the one that the experiment revealed.

In another experiment, an even more ingenious procedure was used. Two groups of students were shown the same movie in the same auditorium, only the first group of students watched it in silence, and for the second group of students, a chainsaw was specially adjusted, which buzzed outside the window while watching. After watching, they asked me to tell them how much I liked the movie, and again to give an explanation of why I liked or disliked it that much. It is reasonable to assume that the group of students who watched the movie in silence liked the movie more than those who watched with a chainsaw outside the window. And so it turned out: none of the students pointed to the chainsaw as a factor that influences their assessment of the film.

That is, we see that people are fully aware of the impact, fully aware of their response, but not aware of what aspects of the impact could affect the response. Many so-called conscious priming effects are arranged exactly according to this principle, both in the purely cognitive, cognitive sphere, and in the emotional one. Strictly speaking, emotional priming is one of the well—known black PR technologies. Let’s say we have a speech by a candidate who is being elected to a particular post, and right before this candidate’s speech we can put on a television program, for example, a report on the state of urban landfills or a report on a kindergarten holiday. It is clear that the candidate’s speech has no connection with this previous video, but nevertheless, research shows that the emotional mood of the video or the emotional priming effect have a fairly strong influence on the assessment of the candidate’s speech itself.

Exactly the same thing is possible in the cognitive sphere. We accidentally hear two people talking about visiting a polyclinic in a subway car, we come to work, colleagues there solve a crossword puzzle, ask us to suggest a four-letter profession, the first thing we say is “doctor”, most likely not correlating the reproduction of this information with what we heard in the subway car, but being pre-configured to extract it under appropriate conditions.

If we talk about experimental studies of unconscious processes in cognition, the so-called cognitive unconscious, then there are three large areas. First, it is the study of the so-called subthreshold perception, perception without awareness, that is, the processing of information that we have not seen or heard, but which has influenced the further course of our cognitive processes or our behavior. Secondly, the research of the so-called implicit memory, or the content of memory, to which we do not have direct access.

That is, we do not remember or do not know that we remember something, but at the same time we are able to extract and use this information in appropriate conditions. As a matter of fact, an example of a priming effect with the reproduction of the names of professions is just a fairly typical manifestation of implicit memory. We had already forgotten about this conversation on the subway, but we pulled out the relevant content. In some cases, it can be more interesting.: in principle, we don’t know that we remember anything, but we can, for example, express some thought, passing it off as our own, and believing that it is ours, but in fact it may turn out that we read it in a book a year ago, which is also about They completely forgot.

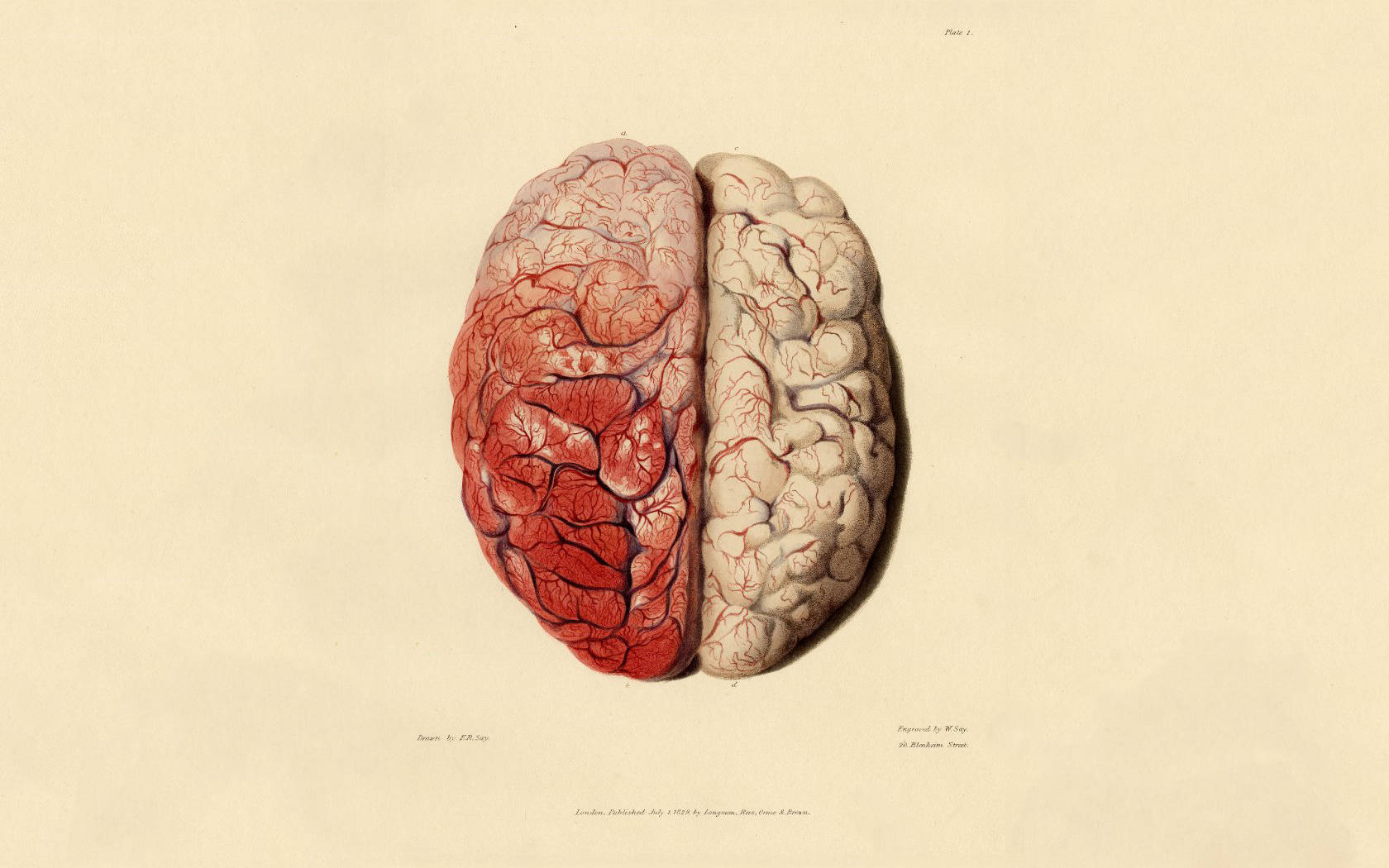

A third group of phenomena is closely related to the phenomena of implicit memory, which are studied in the context of the study of the cognitive unconscious or unconscious processes in cognition. This is the so-called implicit learning or the formation of skills without awareness of what we have learned, and in some cases without awareness of the very fact of learning. A situation where a person does not know at all and does not remember that he has encountered a certain skill, but owns it, is usually a clinical case. Patients with specific memory impairments who do not form new traces in long-term memory, as a rule, due to lesions of the hippocampus, the brain structure that participates in the formation of such traces.

Such a patient stays forever in his memory, to which he has direct access on the day when the traumatic event occurred. New traces of memory, new acquaintances, new books do not leave any traces in his memory. But it turns out that such patients develop complex cognitive skills quite easily. For example, they can learn mirror reading or mirror drawing, drawing while tracing the traces of the drawing in the mirror, rather than directly. It is very difficult, and the patient says that he has never done this in his life and will not be able to, but every time he gets better and more effective.

People without pathology in the hippocampus can also learn something implicitly. A typical example is learning how to type on a keyboard. If a person has not studied this on purpose, most likely, he types text quite effectively, but if you pester him with the question of where the English letter V or letter P is on the keyboard, it will most likely be difficult for him to answer this question. He will click on this letter quickly when he needs to type a word in Latin letters, but he will not be able to give an answer.

In the field of implicit learning, there are probably the most interesting experimental techniques through which we can probe unconscious processes in cognition. It turns out that we can identify rules for making sequences that we are not aware of, or we can learn complex management rules, for example, a sugar factory, which we can quite effectively bring to the required state, to the required level of profit, simply by managing it. But we can’t say how we do it if we’re asked questions, as one of the classics of cognitive psychology, Donald Broadbent, has shown in his research. In fact, there is much more work going on outside of our consciousness than it may seem.

Source: Postnauka