New functions of gut microflora

“We are what we eat.” That’s what Hippocrates said. But could he have imagined how right he was? Judging by the latest scientific data, the food consumed has a very strong effect on our gut microflora, which ultimately affects our body. Moreover, it has quite a tangible effect — for example, by changing our weight! It turns out to be a vicious circle: human — microflora — human.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

What is normoflora and what are its functions?

Picture 1. The main functions of normal microflora. [2]

The metabolic activity of the intestinal microbiota, in addition to satisfying the bacteria’s own needs, helps to extract calories from the food consumed by the host, helps to store this energy in its fat depots, that is, to form adipose tissue. In experiments with gnotobiotic (antimicrobial) mice populated with certain bacteria, it was shown that the intestinal microflora ensures the decomposition of food polysaccharides that are indigestible by the host into digestible forms — but this is hardly news. The finding was that this process was accompanied by increased absorption of monosaccharides from the intestine and their entry into the portal vein, possibly due to an increase in the density of the capillary network in the mucous membrane of the small intestine under the influence of the microbiota. This led to increased hepatic lipogenesis, that is, the synthesis of fatty acids from carbohydrates. The fact is that liver cells respond to an increase in blood glucose and insulin levels by expressing the genes of the transcription factors ChREBP and SREBP-1, which activate genes for the biosynthesis of triglycerides, that is, fats. Increased production of these transcription factors was observed after colonization of mouse intestines with microbiota. In addition, intestinal bacteria helped to place newly produced triglycerides in fat cells (adipocytes), interfering with the work of host genes: the microflora increased the activity of lipoprotein lipase necessary for this, suppressing the synthesis of its inhibitor in the epithelium of the small intestine.

However, it is worth recalling here that we were talking about mice, about a specific enterotype of their microflora (a biocenosis dominated by certain groups of bacteria) and, in general, about the basic functions of the microbiota. Therefore, based on this work, it is not necessary to draw a conclusion about the harmful effects of any intestinal bacteria on the host, it is just how the hypothesis of multiple and interrelated mechanisms of the intestinal microbiota’s influence on the host’s energy metabolism appeared, and with it the hope that correcting this influence will help to cope with the epidemic of obesity [5]. The authors suggested that one individual’s microbial “bioreactor” may be more energy efficient than another’s. And the factors influencing this will be discussed later.

Picture 1. The main functions of normal microflora. [2]

The metabolic activity of the intestinal microbiota, in addition to satisfying the bacteria’s own needs, helps to extract calories from the food consumed by the host, helps to store this energy in its fat depots, that is, to form adipose tissue. In experiments with gnotobiotic (antimicrobial) mice populated with certain bacteria, it was shown that the intestinal microflora ensures the decomposition of food polysaccharides that are indigestible by the host into digestible forms — but this is hardly news. The finding was that this process was accompanied by increased absorption of monosaccharides from the intestine and their entry into the portal vein, possibly due to an increase in the density of the capillary network in the mucous membrane of the small intestine under the influence of the microbiota. This led to increased hepatic lipogenesis, that is, the synthesis of fatty acids from carbohydrates. The fact is that liver cells respond to an increase in blood glucose and insulin levels by expressing the genes of the transcription factors ChREBP and SREBP-1, which activate genes for the biosynthesis of triglycerides, that is, fats. Increased production of these transcription factors was observed after colonization of mouse intestines with microbiota. In addition, intestinal bacteria helped to place newly produced triglycerides in fat cells (adipocytes), interfering with the work of host genes: the microflora increased the activity of lipoprotein lipase necessary for this, suppressing the synthesis of its inhibitor in the epithelium of the small intestine.

However, it is worth recalling here that we were talking about mice, about a specific enterotype of their microflora (a biocenosis dominated by certain groups of bacteria) and, in general, about the basic functions of the microbiota. Therefore, based on this work, it is not necessary to draw a conclusion about the harmful effects of any intestinal bacteria on the host, it is just how the hypothesis of multiple and interrelated mechanisms of the intestinal microbiota’s influence on the host’s energy metabolism appeared, and with it the hope that correcting this influence will help to cope with the epidemic of obesity [5]. The authors suggested that one individual’s microbial “bioreactor” may be more energy efficient than another’s. And the factors influencing this will be discussed later. The microflora of people with normal weight and obese differs

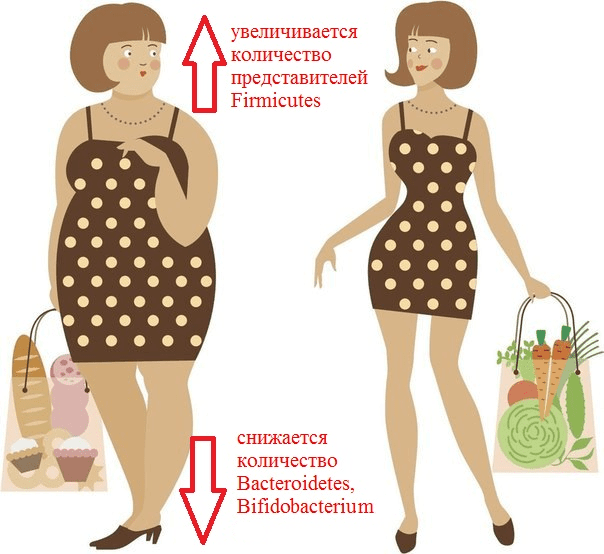

Picture 2. What is remarkable about the composition of the intestinal microflora of an obese person?

It has been repeatedly revealed that obesity increases the number of representatives of the Firmicutes type (for example, Clostridium coccoides, C. leptum) and the Enterobacteriaceae family (Esherichia coli). At the same time, the number of representatives of the Bacteroidetes type (Bacteroides, Prevotella) is decreasing, and populations of bacteria of the genera Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are decreasing [7]. It has previously been shown that a high-fat diet promotes inflammation of the intestinal mucosa, mediated by a decrease in the number of lactobacilli. This inflammation predisposes to the development of obesity and insulin resistance, that is, type 2 diabetes. In 2016, experiments with mice were able to establish a link between these conditions and a deficiency of specific strains. Lactobacillus reuteri in Peyer’s patches. The fact is that fat-rich foods ensure the selection of bacterial strains that are resistant to oxidative stress. And these turned out to be lactobacilli, which secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines. Conversely, the “good” strains of L. reuteri, producers of anti—inflammatory substances, were displaced from the population [8].

As already mentioned, the analysis of the intestinal microbiome revealed a sharp decrease in the proportion of Bacteroidetes and an increase in the proportion of Firmicutes in mice with hereditary obesity compared to normal mice [9]. The same changes were often observed in humans: in one study, 12 obese patients differed from the lean control group by having a reduced bacterial content Bacteroidetes and elevated Firmicutes. Then the patients were transferred to a low-calorie diet (a diet with a restriction of fats and carbohydrates) and changes in the composition of their intestinal microflora were monitored for a year. It turned out that the diet significantly reduced the number of Firmicutes and increased the proportion of Bacteroidetes, but most importantly, these changes correlated with the degree of weight loss [9]. Nevertheless, the relationship of body mass index with the proportion of Bacteroidetes/ Firmicutes has not yet been proven [10].

Picture 2. What is remarkable about the composition of the intestinal microflora of an obese person?

It has been repeatedly revealed that obesity increases the number of representatives of the Firmicutes type (for example, Clostridium coccoides, C. leptum) and the Enterobacteriaceae family (Esherichia coli). At the same time, the number of representatives of the Bacteroidetes type (Bacteroides, Prevotella) is decreasing, and populations of bacteria of the genera Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are decreasing [7]. It has previously been shown that a high-fat diet promotes inflammation of the intestinal mucosa, mediated by a decrease in the number of lactobacilli. This inflammation predisposes to the development of obesity and insulin resistance, that is, type 2 diabetes. In 2016, experiments with mice were able to establish a link between these conditions and a deficiency of specific strains. Lactobacillus reuteri in Peyer’s patches. The fact is that fat-rich foods ensure the selection of bacterial strains that are resistant to oxidative stress. And these turned out to be lactobacilli, which secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines. Conversely, the “good” strains of L. reuteri, producers of anti—inflammatory substances, were displaced from the population [8].

As already mentioned, the analysis of the intestinal microbiome revealed a sharp decrease in the proportion of Bacteroidetes and an increase in the proportion of Firmicutes in mice with hereditary obesity compared to normal mice [9]. The same changes were often observed in humans: in one study, 12 obese patients differed from the lean control group by having a reduced bacterial content Bacteroidetes and elevated Firmicutes. Then the patients were transferred to a low-calorie diet (a diet with a restriction of fats and carbohydrates) and changes in the composition of their intestinal microflora were monitored for a year. It turned out that the diet significantly reduced the number of Firmicutes and increased the proportion of Bacteroidetes, but most importantly, these changes correlated with the degree of weight loss [9]. Nevertheless, the relationship of body mass index with the proportion of Bacteroidetes/ Firmicutes has not yet been proven [10]. Metabolic changes

The role of microflora in the development of type 1 and type 2 diabetes

- Immunostimulating filament bacteria: they are finally tamed!;

- Microflora of the gastrointestinal tract. Propionics website;

- Oleskin A.V. (2009). Neurochemistry, symbiotic microflora and nutrition (biopolitical approach). Gastroenterology of St. Petersburg. 1, 8–16;

- Calm as GABA;

- Dibaise Bäckhed F., Ding H., Wang T., Hooper L.V., Koh G.Y., Nagy A. et al. (2004). The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101 (44), 15718–15723;

- The zoo in my stomach;

- Glick-Bauer M. and Yeh M.-C. (2014). The Health advantage of a vegan diet: exploring the gut microbiota connection. Nutrients. 6 (11), 4822–4838;

- Sun J., Qiao Y., Qi C., Jiang W., Xiao H., Shi Y., Le G.W. (2016). High-fat-diet-induced obesity is associated with decreased antiinflammatory Lactobacillus reuteri sensitive to oxidative stress in mouse Peyer’s patches. Nutrition. 32 (2), 265–272;

- Ley R.E., Bдckhed F., Turnbaugh P.J., Lozupone C.A., Knight R.D., Gordon J.I. (2005). Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 11070–11075;

- Khan M.J., Gerasimidis K., Edwards C.A., Shaikh M.G. (2016). Role of gut microbiota in the aetiology of obesity: proposed mechanisms and review of the literature. J. Obes. 2016, 7353642;

- Final Report Summary — METAHIT (Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract). Website of the European Commission CORDIS (Community Research and Development Information Service);

- Koeth R.A., Levison B.S., Culley M.K., Buffa J.A., Wang Z., Gregory J.C. et al. (2014). γ-Butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metab. 20 (5), 799–812;

- Микробиом кишечника: мир внутри нас;

- Korner J. and Leibel R.I. (2003). To eat or not to eat — how the gut talks to the brain. N. Engl. J. Med.349, 926–928;

- Brugman S., Klatter F.A., Visser J.T., Wildeboer-Veloo A.C., Harmsen H.J., Rozing J., Bos N.A. (2006). Antibiotic treatment partially protects against type 1 diabetes in the bio-breeding diabetes-prone rat: is the gut flora involved in the development of type 1 diabetes? Diabetologia. 49, 2105–2108;

- Paun A., Yau C., Danska J.S. (2016). Immune recognition and response to the intestinal microbiome in type 1 diabetes. J. Autoimmun. 71, 10–18;

- Costa F.R., Françozo M.C., de Oliveira G.G., Ignacio A., Castoldi A., Zamboni D.S. et al. (2016). Gut microbiota translocation to the pancreatic lymph nodes triggers NOD2 activation and contributes to T1D onset. J. Exp. Med. 213 (7), 1223–1239.

Published

Июль, 2024

Duration of reading

About 5-6 minutes

Category

Genetics

Share