Gut microbiome: the world inside us

The human gut microbiome is a unique collection of microorganisms. Its invisible presence mediates a number of important processes, from metabolic and immune to cognitive, and the deviation of its composition from the norm leads to the development of various pathological conditions: allergic and autoimmune diseases, diabetes mellitus, obesity, etc. The qualitative and quantitative composition of the microbiome, on which future human health largely depends, is determined in infancy. This article will be devoted to the processes of its formation.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Microbiome: the beginning

Delivery

- L. crispatus (type I microbiome);

- L. gasseri (type II microbiome);

- L. iners (type III microbiome);

- L. jensenii (type V microbiome).

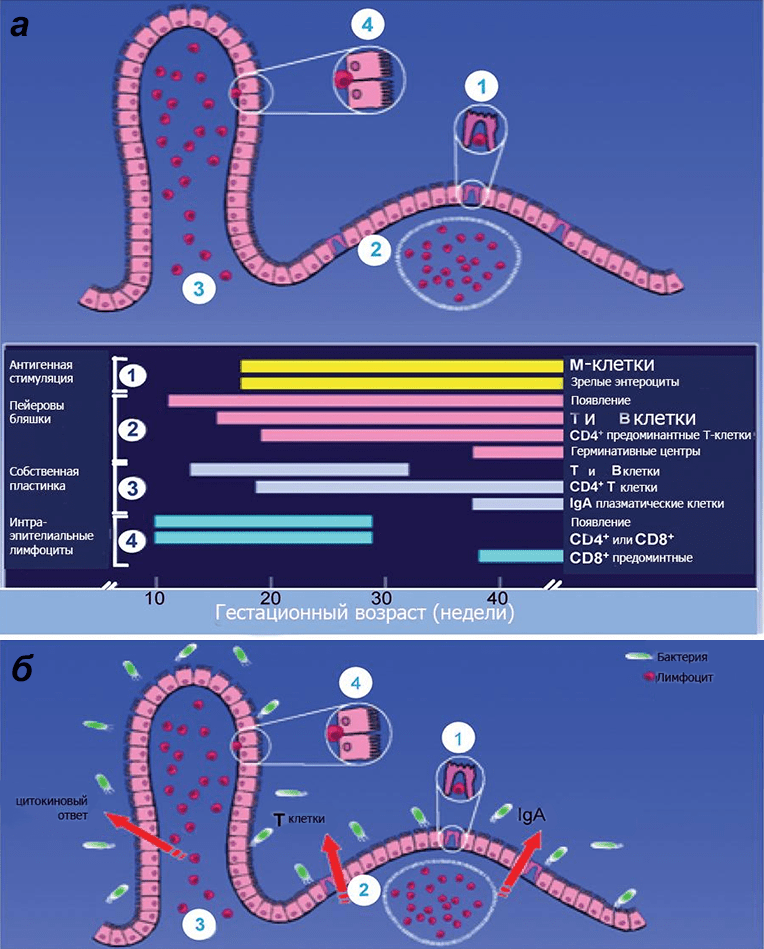

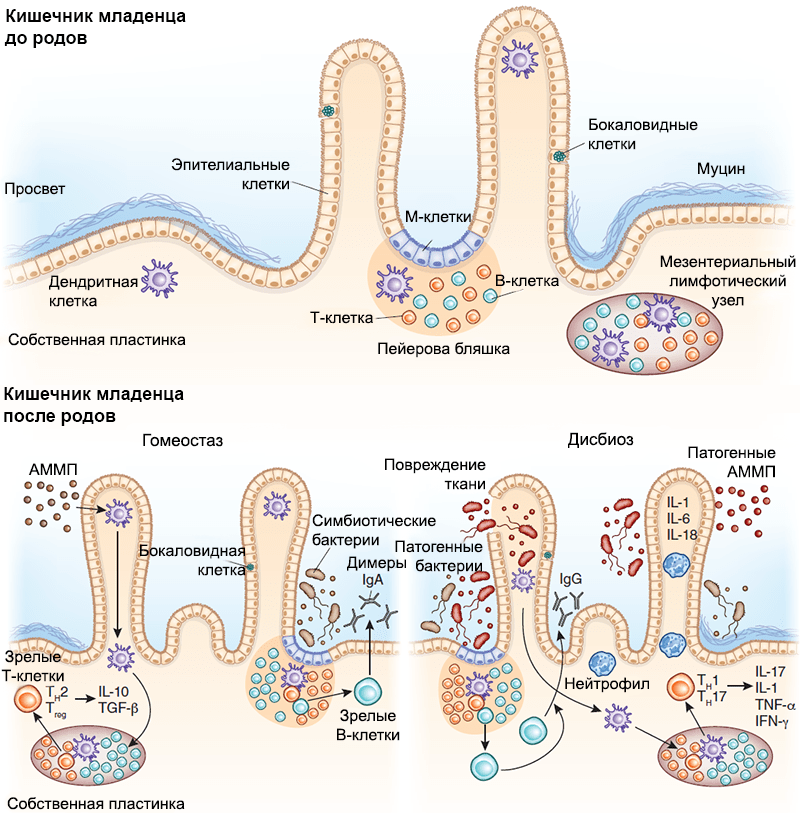

Picture 1. Scheme of immune protection of the intestinal mucosa of the fetus depending on gestational age. a — In a baby born on time, all the components of the immune defense of the mucous membrane are mature. b — However, in order for the immune system to become functional, it must be stimulated by primary colonizers. The immune defense of the intestine includes: specialized epithelium, or M-cells (1), Peyer’s plaques (2), interstitial (3) and intraepithelial (4) lymphocytes mediating the development of immune reactions. Among the lymphoid formations of the intestine, single lymph nodes (located mainly in the distal intestine) and Peyer’s plaques (located mainly in the ileum) are distinguished. The latter are formed by grouped lymphatic follicles protruding the epithelium into the intestinal lumen in the form of a dome, and interstitial clusters of lymphoid tissue. The epithelium of the mucous membrane in the plaque area contains up to 10% of specific micro-folded (M—) cells that provide transepithelial transport, the mechanism of which is transcytosis: due to a thin glycocalyx, they actively absorb macromolecules (including antigens) from the intestinal lumen with the apical surface, transfer them through their cytoplasm as part of the endosome and transfer them to immunocompetent Peyer’s cells through exocytosis. plaques. To speed up the process, M cells form “pockets” from below, filled with an “immune vinaigrette” of B cells, plasmocytes, T cells, macrophages, and antigen-presenting dendritic cells.

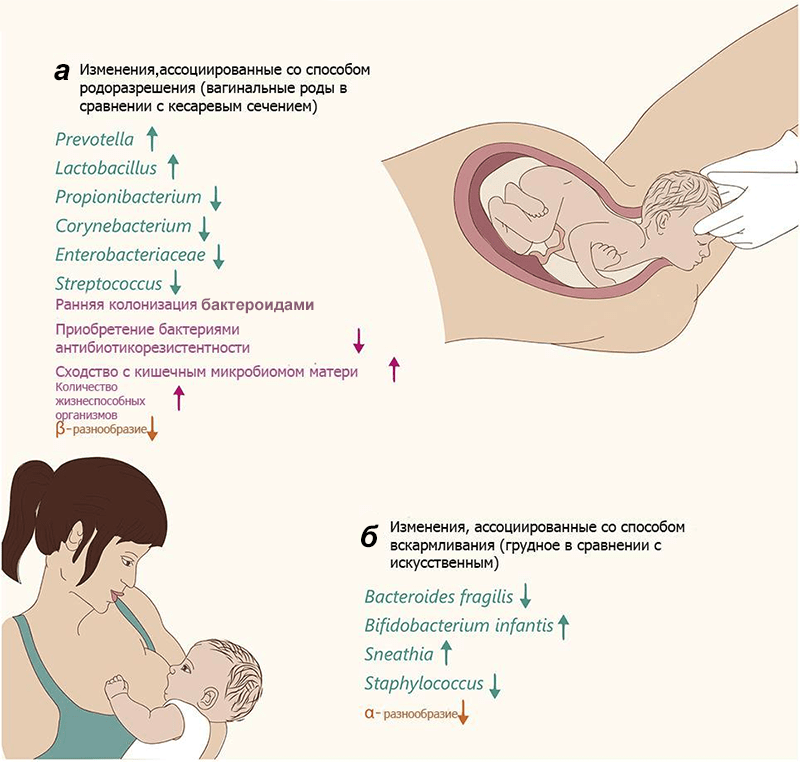

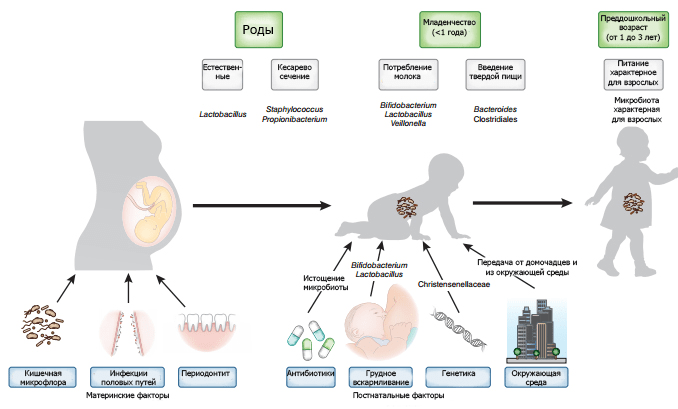

Nevertheless, it is obvious that the nature of delivery affects the microbiome of the newborn (Pic. 2). However, it is still unclear whether these differences affect the health of an adult individual.: Although some epidemiological studies demonstrate a link between cesarean section and various diseases (Table. 1), the reason for their development has not been definitively clarified.

Picture 1. Scheme of immune protection of the intestinal mucosa of the fetus depending on gestational age. a — In a baby born on time, all the components of the immune defense of the mucous membrane are mature. b — However, in order for the immune system to become functional, it must be stimulated by primary colonizers. The immune defense of the intestine includes: specialized epithelium, or M-cells (1), Peyer’s plaques (2), interstitial (3) and intraepithelial (4) lymphocytes mediating the development of immune reactions. Among the lymphoid formations of the intestine, single lymph nodes (located mainly in the distal intestine) and Peyer’s plaques (located mainly in the ileum) are distinguished. The latter are formed by grouped lymphatic follicles protruding the epithelium into the intestinal lumen in the form of a dome, and interstitial clusters of lymphoid tissue. The epithelium of the mucous membrane in the plaque area contains up to 10% of specific micro-folded (M—) cells that provide transepithelial transport, the mechanism of which is transcytosis: due to a thin glycocalyx, they actively absorb macromolecules (including antigens) from the intestinal lumen with the apical surface, transfer them through their cytoplasm as part of the endosome and transfer them to immunocompetent Peyer’s cells through exocytosis. plaques. To speed up the process, M cells form “pockets” from below, filled with an “immune vinaigrette” of B cells, plasmocytes, T cells, macrophages, and antigen-presenting dendritic cells.

Nevertheless, it is obvious that the nature of delivery affects the microbiome of the newborn (Pic. 2). However, it is still unclear whether these differences affect the health of an adult individual.: Although some epidemiological studies demonstrate a link between cesarean section and various diseases (Table. 1), the reason for their development has not been definitively clarified.

Picture 2. Changes in the microbiome in newborns. The text color and arrows indicate changes in specific varieties (green), general changes (pink), and community diversity (orange). but — Changes in infants born naturally, relative to surgically extracted ones. b — Changes in breastfed infants relative to “artificial babies”. α-diversity is the species diversity within the studied community, β-diversity is the species diversity between communities of a given area (according to R. Whittaker).

Picture 2. Changes in the microbiome in newborns. The text color and arrows indicate changes in specific varieties (green), general changes (pink), and community diversity (orange). but — Changes in infants born naturally, relative to surgically extracted ones. b — Changes in breastfed infants relative to “artificial babies”. α-diversity is the species diversity within the studied community, β-diversity is the species diversity between communities of a given area (according to R. Whittaker). Breastfeeding

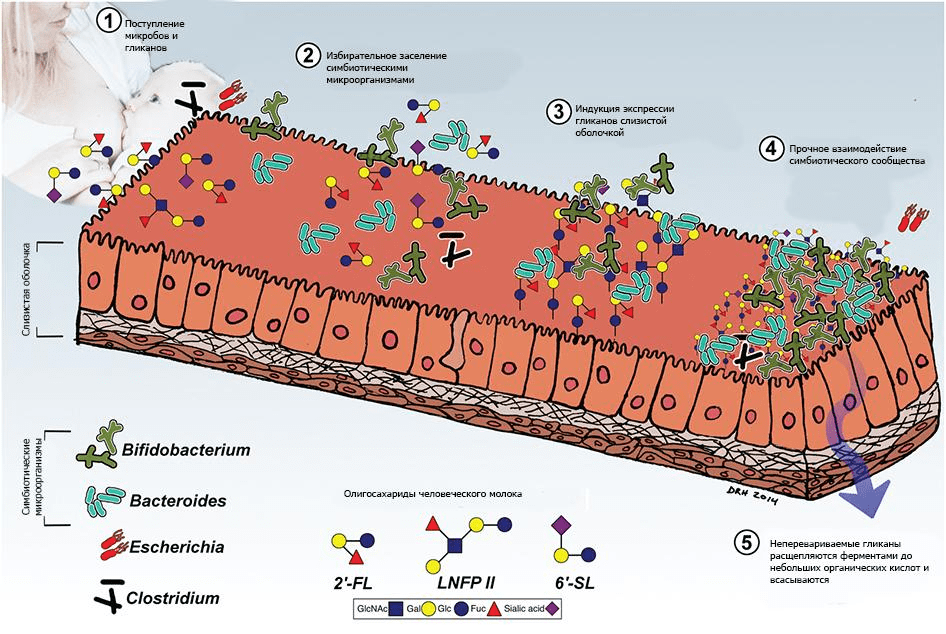

Pic 3. Interaction of human milk glycans and microbiota. The interaction of the newborn with maternal and environmental microorganisms is mediated by the consumption of colostrum and the glycans contained in it (human milk oligosaccharides, OHMS). PMPS have prebiotic, anti—adhesive, and anti—inflammatory activities, facilitate the expansion of symbionts, especially Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium, and inhibit the growth and adhesion of opportunistic and obligate pathogens.

Another factor mediating the formation of the microbiome is the so—called enteromammary axis, a system that ensures the transport of bacteria from the intestine (future) the mother’s mammary glands. Its primary link is intestinal dendritic cells, which capture bacteria and transport them to local lymphoid follicles [1]. A specific immunoglobulin is produced there. These dendritic cells and immunoglobulin-secreting lymphocytes circulate in the blood, but can selectively return to the intestine due to the interaction between β7-integrins and adhesion molecules secreted by endotheliocytes (addressins, MAdCAM-1). Mammary endothelial cells synthesize MAdCAM-1 molecules during pregnancy, ensuring the selective entry of “programmed” dendritic cells containing intestinal bacteria into the gland [33]. In addition to bacteria, colostrum and mother’s milk contain T cells producing β7-integrins and plasma cells producing specific IdA [34]. There are also cytokines in milk, the composition of which depends on the immunological experience of the mother acquired during life.

There is a theory suggesting the transfer of microorganisms from the baby’s mouth to the mother’s mammary gland, followed by the production of specific antibodies in her body and their entry into the child’s gastrointestinal tract [34]. The assumption is confirmed by the fact that identical bacteria are found in the mouth of the newborn and in breast milk. Gemella, Veillonella, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus [35], [36]. Although there is evidence that they are present in colostrum even before breastfeeding (even after careful hygienic treatment of the gland, samples of expressed milk contain bacteria from the skin and intestinal microbiome of the mother [37]), this still does not negate the possibility of implementing a reverse skid mechanism.

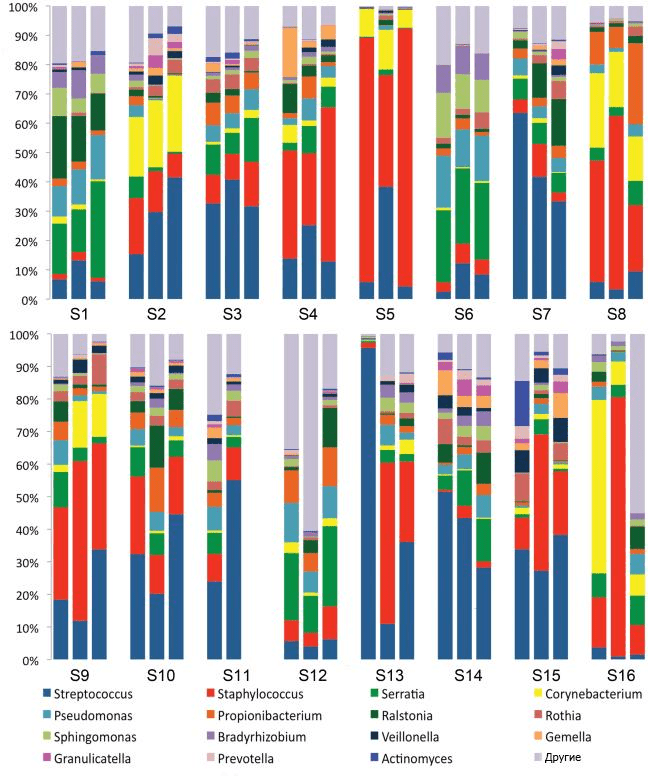

In 2011, scientists from the United States found nine taxonomic units of bacteria in milk samples from 16 women. Having thus established that the microbial composition of milk is extremely diverse, they proposed the concept of the “core of the microbiome of human milk” (pic. 4) [35]. Later, it became clear that the microbiome changes throughout the lactation period. For example, colostrum is dominated by bacteria. Weissella, Leuconostoc, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Lactococcus, and in the milk produced in the first six months after birth, apparently due to frequent contact with the inhabitants of the baby’s mouth, there is a “bias” towards Veillonella, Leptotrichia and Prevotella — which again confirms the theory of reverse drift [37].

Pic 3. Interaction of human milk glycans and microbiota. The interaction of the newborn with maternal and environmental microorganisms is mediated by the consumption of colostrum and the glycans contained in it (human milk oligosaccharides, OHMS). PMPS have prebiotic, anti—adhesive, and anti—inflammatory activities, facilitate the expansion of symbionts, especially Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium, and inhibit the growth and adhesion of opportunistic and obligate pathogens.

Another factor mediating the formation of the microbiome is the so—called enteromammary axis, a system that ensures the transport of bacteria from the intestine (future) the mother’s mammary glands. Its primary link is intestinal dendritic cells, which capture bacteria and transport them to local lymphoid follicles [1]. A specific immunoglobulin is produced there. These dendritic cells and immunoglobulin-secreting lymphocytes circulate in the blood, but can selectively return to the intestine due to the interaction between β7-integrins and adhesion molecules secreted by endotheliocytes (addressins, MAdCAM-1). Mammary endothelial cells synthesize MAdCAM-1 molecules during pregnancy, ensuring the selective entry of “programmed” dendritic cells containing intestinal bacteria into the gland [33]. In addition to bacteria, colostrum and mother’s milk contain T cells producing β7-integrins and plasma cells producing specific IdA [34]. There are also cytokines in milk, the composition of which depends on the immunological experience of the mother acquired during life.

There is a theory suggesting the transfer of microorganisms from the baby’s mouth to the mother’s mammary gland, followed by the production of specific antibodies in her body and their entry into the child’s gastrointestinal tract [34]. The assumption is confirmed by the fact that identical bacteria are found in the mouth of the newborn and in breast milk. Gemella, Veillonella, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus [35], [36]. Although there is evidence that they are present in colostrum even before breastfeeding (even after careful hygienic treatment of the gland, samples of expressed milk contain bacteria from the skin and intestinal microbiome of the mother [37]), this still does not negate the possibility of implementing a reverse skid mechanism.

In 2011, scientists from the United States found nine taxonomic units of bacteria in milk samples from 16 women. Having thus established that the microbial composition of milk is extremely diverse, they proposed the concept of the “core of the microbiome of human milk” (pic. 4) [35]. Later, it became clear that the microbiome changes throughout the lactation period. For example, colostrum is dominated by bacteria. Weissella, Leuconostoc, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Lactococcus, and in the milk produced in the first six months after birth, apparently due to frequent contact with the inhabitants of the baby’s mouth, there is a “bias” towards Veillonella, Leptotrichia and Prevotella — which again confirms the theory of reverse drift [37].

Picture 4. Nine bacterial taxonomic units found in milk samples from 16 women in 2011. The observed communities turned out to be quite complex, and with the relative constancy of the composition of one group of subjects, the other showed changes over time.

Maternal health also plays an important role in shaping the microbial composition of milk. In the first month of lactation, the milk of obese women is dominated by Lactobacillus, however, after six months they are replaced by representatives of the genus Staphylococcus [37], which, as studies show, begin to prevail in the intestines of obese infants, and therefore scientists have suggested the existence of a link between the features of the human milk microbiome and paratrophy in children.

The gradual weaning of the baby and the transition to solid foods also play an important role in the formation of bacterial diversity. After breast—feeding is completed, bacteria typical of an adult appear in the microbiome of the baby’s intestine. Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and the Clostridia class: Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, and Anaerostipes [19], [38].

Picture 4. Nine bacterial taxonomic units found in milk samples from 16 women in 2011. The observed communities turned out to be quite complex, and with the relative constancy of the composition of one group of subjects, the other showed changes over time.

Maternal health also plays an important role in shaping the microbial composition of milk. In the first month of lactation, the milk of obese women is dominated by Lactobacillus, however, after six months they are replaced by representatives of the genus Staphylococcus [37], which, as studies show, begin to prevail in the intestines of obese infants, and therefore scientists have suggested the existence of a link between the features of the human milk microbiome and paratrophy in children.

The gradual weaning of the baby and the transition to solid foods also play an important role in the formation of bacterial diversity. After breast—feeding is completed, bacteria typical of an adult appear in the microbiome of the baby’s intestine. Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and the Clostridia class: Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, and Anaerostipes [19], [38]. Immunity

Picture 5. Intestinal epithelial barrier. The simple cylindrical epithelium has mechanisms of physical and biochemical adaptation to microbial colonization that maintain the integrity of the barrier. These include: actin-rich microvilli; dense contacts of epithelial cells (a); mucins that form a “sieve— for sieving glycocalyx molecules; production of various antimicrobial peptides. M cells covering Peyer’s plaques and single lymphoid follicles provide translocation of molecules from the intestinal lumen under the epithelium to antigen-presenting cells. Dendrites of specialized dendritic cells (DCS) can penetrate into the intestinal lumen through tight contacts (b).

Scientists have suggested that intestinal bacteria not only stimulate its lymphoid elements, but also affect the intestinal mucosal barrier, stimulating the formation of microvilli [39], [40] and dense contacts [41].

Picture 5. Intestinal epithelial barrier. The simple cylindrical epithelium has mechanisms of physical and biochemical adaptation to microbial colonization that maintain the integrity of the barrier. These include: actin-rich microvilli; dense contacts of epithelial cells (a); mucins that form a “sieve— for sieving glycocalyx molecules; production of various antimicrobial peptides. M cells covering Peyer’s plaques and single lymphoid follicles provide translocation of molecules from the intestinal lumen under the epithelium to antigen-presenting cells. Dendrites of specialized dendritic cells (DCS) can penetrate into the intestinal lumen through tight contacts (b).

Scientists have suggested that intestinal bacteria not only stimulate its lymphoid elements, but also affect the intestinal mucosal barrier, stimulating the formation of microvilli [39], [40] and dense contacts [41].

Picture 6. The interaction between the intestinal immune system and the baby’s microbiome. The development of secondary lymphoid structures, including Peyer’s plaques and single lymph nodes, occurs in utero, long before bacterial colonization begins. With its onset, the mechanisms of interaction between the host’s immune system and symbiont bacteria are adjusted. M cells transfer bacterial antigens to dendritic cells by transcytosis, which present them, mediating the T-dependent maturation of B lymphocytes and promoting the secretion of IgA by plasma cells, which plays an important role in protecting against pathogens. Bacteria can also translocate through dendritic cells and be presented to lymph node T cells, inducing their differentiation. The lower left panel is an AMPM — associated molecular pattern with microorganisms. Under conditions of homeostasis, AMPS associated with symbiont bacteria stimulate the production of regulatory cytokines (IL-25, IL-33, thymus stromal lymphopoietin and transforming growth factor, TGF-β). Signal transduction to dendritic cells stimulates the development of regulatory T cells and promotes the secretion of IL-10.Lower right panel — In a state of dysbiosis, a decrease in the number of symbiont bacteria leads to the proliferation of pathogens. Pathogenic AMPS induce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and IL-18), promoting the proliferation of effector T cells. These T cells differentiate into CD4+Th1 and Th17 and secrete IL-17, tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which attract neutrophils to the inflammatory site, protecting the host body from pathogens.

Investigating the effect of bacteria on the protective mechanisms of the intestine (Fig. 6), scientists artificially colonized bacteria Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron intestines of antimicrobial mice. The intestinal epithelial RNA was then analyzed for changes in gene expression [42]. Extensive activation of epitheliocyte genes was noted, which regulated the function of the epithelial barrier and promoted increased production of the IdA receptor. This study perfectly reflects the effect of bacterial colonization on the intestines of a newborn, because in this context it is the same, practically bacterial-free organism.

All new works emphasize the important role of bacterial colonization in the formation and maintenance of mammalian health. In a recent experiment devoted to studying the functions of Toll-like receptors, a gene for an important component of innate immunity, the TLR5 receptor, located on the basolateral surface of mouse enterocytes, was knocked out. This led to the following: the mice began to overeat regularly and eventually developed a metabolic syndrome accompanied by a change in the composition of the intestinal microbiota. It has been suggested that the microbiome may serve as an indicator of the development of many diseases. But the scientists went further and transplanted the “pathological” microbiota from TLR5-deficient individuals into antimicrobial mice with a normal receptor, and those also showed signs of metabolic syndrome. That is, the microbiome may serve not only as an indicator of systemic problems, but also directly participate in their occurrence. Interestingly, dietary restriction in TLR5-deficient mice prevented the development of obesity, but not insulin resistance [43].

In general, the connection of colonization by symbiont bacteria with the development of both acquired and innate immunity has been demonstrated repeatedly. It was found that the interaction of enterocyte receptors and intestinal immune cells with microbial antigens causes a natural, self-limiting inflammatory response. In this way, the mechanisms of the innate immune response make it possible to prevent pathogens from penetrating the intestinal epithelial barrier, while distinguishing them from harmless symbionts (Pic. 6) [44], [45]. When a baby leaves the womb, it comes into contact with a large number of bacteria. And in order to avoid a continuous inflammatory reaction in response to intestinal colonization, the expression of these receptors, in particular TLR2 and TLR4, decreases [46]. Unfortunately, in children born prematurely, the described mechanisms are still immature, which often leads to the development of necrotizing enterocolitis [47].

Recent studies have shown that intestinal bacteria can also contribute to the development of immune tolerance, that is, protection against excessive immune reactions. These observations are extremely relevant for the development of possible therapeutic interventions, because many bacterial species have a quantitative advantage only in the early stages of colonization, during breastfeeding (see the chapter “Microbiome and breastfeeding”). How were the symbionts linked to immunotolerance? For example, polysaccharide And the capsules Bacteroides fragilis can interact with TLR2 receptors of intestinal dendritic cells, activating the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines that create a specific microenvironment for bacteria [48]. Some species of clostridia similarly increase the number of regulatory T-cells — controllers that suppress the immune response if the T-effectors are unreasonably rampant, thereby preventing IgE-mediated diseases [49]. Thus, specific microorganisms present in breast milk can determine the degree of an individual’s “allergy” even in infancy: these mechanisms make it possible to develop tolerance to “beneficial” antigens and bacteria, preventing the further development of allergies and autoimmune diseases.

Picture 6. The interaction between the intestinal immune system and the baby’s microbiome. The development of secondary lymphoid structures, including Peyer’s plaques and single lymph nodes, occurs in utero, long before bacterial colonization begins. With its onset, the mechanisms of interaction between the host’s immune system and symbiont bacteria are adjusted. M cells transfer bacterial antigens to dendritic cells by transcytosis, which present them, mediating the T-dependent maturation of B lymphocytes and promoting the secretion of IgA by plasma cells, which plays an important role in protecting against pathogens. Bacteria can also translocate through dendritic cells and be presented to lymph node T cells, inducing their differentiation. The lower left panel is an AMPM — associated molecular pattern with microorganisms. Under conditions of homeostasis, AMPS associated with symbiont bacteria stimulate the production of regulatory cytokines (IL-25, IL-33, thymus stromal lymphopoietin and transforming growth factor, TGF-β). Signal transduction to dendritic cells stimulates the development of regulatory T cells and promotes the secretion of IL-10.Lower right panel — In a state of dysbiosis, a decrease in the number of symbiont bacteria leads to the proliferation of pathogens. Pathogenic AMPS induce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and IL-18), promoting the proliferation of effector T cells. These T cells differentiate into CD4+Th1 and Th17 and secrete IL-17, tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which attract neutrophils to the inflammatory site, protecting the host body from pathogens.

Investigating the effect of bacteria on the protective mechanisms of the intestine (Fig. 6), scientists artificially colonized bacteria Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron intestines of antimicrobial mice. The intestinal epithelial RNA was then analyzed for changes in gene expression [42]. Extensive activation of epitheliocyte genes was noted, which regulated the function of the epithelial barrier and promoted increased production of the IdA receptor. This study perfectly reflects the effect of bacterial colonization on the intestines of a newborn, because in this context it is the same, practically bacterial-free organism.

All new works emphasize the important role of bacterial colonization in the formation and maintenance of mammalian health. In a recent experiment devoted to studying the functions of Toll-like receptors, a gene for an important component of innate immunity, the TLR5 receptor, located on the basolateral surface of mouse enterocytes, was knocked out. This led to the following: the mice began to overeat regularly and eventually developed a metabolic syndrome accompanied by a change in the composition of the intestinal microbiota. It has been suggested that the microbiome may serve as an indicator of the development of many diseases. But the scientists went further and transplanted the “pathological” microbiota from TLR5-deficient individuals into antimicrobial mice with a normal receptor, and those also showed signs of metabolic syndrome. That is, the microbiome may serve not only as an indicator of systemic problems, but also directly participate in their occurrence. Interestingly, dietary restriction in TLR5-deficient mice prevented the development of obesity, but not insulin resistance [43].

In general, the connection of colonization by symbiont bacteria with the development of both acquired and innate immunity has been demonstrated repeatedly. It was found that the interaction of enterocyte receptors and intestinal immune cells with microbial antigens causes a natural, self-limiting inflammatory response. In this way, the mechanisms of the innate immune response make it possible to prevent pathogens from penetrating the intestinal epithelial barrier, while distinguishing them from harmless symbionts (Pic. 6) [44], [45]. When a baby leaves the womb, it comes into contact with a large number of bacteria. And in order to avoid a continuous inflammatory reaction in response to intestinal colonization, the expression of these receptors, in particular TLR2 and TLR4, decreases [46]. Unfortunately, in children born prematurely, the described mechanisms are still immature, which often leads to the development of necrotizing enterocolitis [47].

Recent studies have shown that intestinal bacteria can also contribute to the development of immune tolerance, that is, protection against excessive immune reactions. These observations are extremely relevant for the development of possible therapeutic interventions, because many bacterial species have a quantitative advantage only in the early stages of colonization, during breastfeeding (see the chapter “Microbiome and breastfeeding”). How were the symbionts linked to immunotolerance? For example, polysaccharide And the capsules Bacteroides fragilis can interact with TLR2 receptors of intestinal dendritic cells, activating the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines that create a specific microenvironment for bacteria [48]. Some species of clostridia similarly increase the number of regulatory T-cells — controllers that suppress the immune response if the T-effectors are unreasonably rampant, thereby preventing IgE-mediated diseases [49]. Thus, specific microorganisms present in breast milk can determine the degree of an individual’s “allergy” even in infancy: these mechanisms make it possible to develop tolerance to “beneficial” antigens and bacteria, preventing the further development of allergies and autoimmune diseases. And others…

Picture 7. Factors that ensure the formation of the baby’s microbiome. Infections of a woman’s genital tract can lead to bacterial contamination of the uterus. The intestinal and oral microflora can be transported with blood to the fetus. The nature of delivery forms the primary microflora. Genetics and postnatal factors such as diet, antibiotic use, and environmental exposure have additional effects on the microbiome.

Antibiotics are one of the most commonly prescribed medications for children. Prescribing them to the mother in the postpartum period or to a newborn can disrupt the fragile processes that underlie the formation of the microbiome and cause a number of diseases (Table 1). Recent studies regularly emphasize the importance of understanding the processes leading to neonatal dysbiosis and the further development of pathologies such as type II diabetes and inflammatory bowel diseases or an allergic reaction to milk components [51-56]. Changes in the microbiome caused by antibiotics depend on the method of administration, target, type and dosage of the drug. All this is still poorly understood in infants, which makes it difficult to understand the effect of antibiotic therapy on the formation of normal microflora.

Picture 7. Factors that ensure the formation of the baby’s microbiome. Infections of a woman’s genital tract can lead to bacterial contamination of the uterus. The intestinal and oral microflora can be transported with blood to the fetus. The nature of delivery forms the primary microflora. Genetics and postnatal factors such as diet, antibiotic use, and environmental exposure have additional effects on the microbiome.

Antibiotics are one of the most commonly prescribed medications for children. Prescribing them to the mother in the postpartum period or to a newborn can disrupt the fragile processes that underlie the formation of the microbiome and cause a number of diseases (Table 1). Recent studies regularly emphasize the importance of understanding the processes leading to neonatal dysbiosis and the further development of pathologies such as type II diabetes and inflammatory bowel diseases or an allergic reaction to milk components [51-56]. Changes in the microbiome caused by antibiotics depend on the method of administration, target, type and dosage of the drug. All this is still poorly understood in infants, which makes it difficult to understand the effect of antibiotic therapy on the formation of normal microflora.

| The factor causing the imbalance | Characteristics of the cohort | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Caesarean section | 1.9 million Danish children aged 0-15 years | Asthma, systemic connective tissue diseases, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, immunodeficiency and leukemia |

| 1,255 three-year-olds from the USA | Obesity, high BMI | |

| 2,803 Norwegian children 0-3 years old | Allergic reaction to chicken eggs, fish or nuts | |

| Антибиотикотерапия | 1401 children 0-6 months old from the USA | Asthma and allergies |

| 5,780 British children 0-2 years old | Asthma and eczema | |

| 12,062 Finnish children 0-2 years old | Overweight and obesity | |

| 162820 children aged 2-18 from the USA | Overweight | |

| 9 million British children | Inflammatory bowel diseases | |

| Probiotics | 215 Spanish children 0-6 months old | Reducing the frequency of gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tract infections |

| European Society of Specialists in Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Nutrition Commission | Reducing the incidence of nonspecific gastrointestinal infections | |

| Food additives | 139 African children aged 6-14 | Inflammatory bowel diseases are more common, and colic is less common. |

| Hygiene | 184 children 0-3 years old (study of the purity of pacifiers) | The cleanliness of the pacifiers reduced the risk of asthma, allergies, and sensitization. |

| Pets | 3143 Finnish children 0-1 years old | Reducing the risk of type I diabetes |

Correction

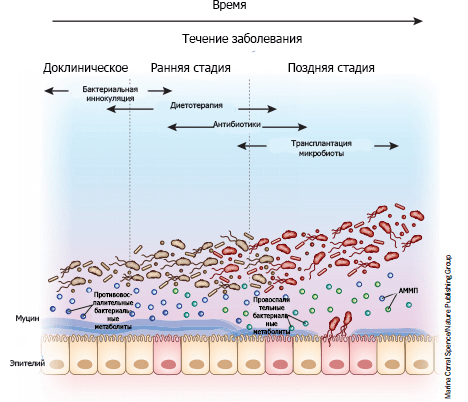

Picture 8. “Microbial therapy” depending on the stage of the disease. In the preclinical stages, the disease is not yet fully manifested: its symptoms (if any) are minimal and non-specific, but subtle biological changes are already taking place. The use of cultures of certain bacterial communities in the early stages of the disease can prevent dysbiosis and the development of pathology with maximum effectiveness. As the disease progresses, the microbiome is enriched with pathogens (shown in red) that produce pro-inflammatory metabolites and thereby activate inflammatory pathways (Fig. 6). The mucous layer protected by the epithelium becomes thinner as pathogens accumulate, exacerbating the course of the disease. At this stage, diet therapy and antibiotics can be used as a radical measure that changes the quantitative and qualitative composition of bacteria. In the later stages, the continued thinning of the mucous layer allows bacteria to break through the epithelial barrier. Then aggressive antibiotic therapy combined with microbiota transplantation can help restore microbial balance. AMP is a microbial—associated molecular pattern.

However, in young children, prolonged use of antibiotics is fraught with a significant risk of complications. The composition of the microbiota can also be changed through diet therapy by eating foods that promote the growth of “beneficial” microorganisms. One example of such a diet is a special enteral nutrition used for the symptomatic treatment of Crohn’s disease in children. It is a specific mixture of all the necessary micro- and macronutrients and therefore can serve as the only source of nutrients for a long time. It is supplied exclusively in liquid form — orally or through a probe — and contributes to achieving clinical remission by creating a kind of “resting mode”: reducing the functional load on the inflamed intestine and reducing its injury [67].

Research in the field of nutrition deficiency has demonstrated that today it is impossible, using diet therapy alone, to significantly influence the composition of the intestinal microbiome, although the study of the influence of nutrition on it continues.

Given the significant impact on health of the microbiota in early childhood, methods aimed at timely, preventive, restoration of microbial balance look very relevant. Recently, it has been shown that the microbiome of newborns born by caesarean section can be restored to a state similar to babies born naturally. Wiping such children with tampons, which were inserted into the mother’s vagina an hour before cesarean section, led to a significant enrichment of their microbiome with representatives of Lactobacillus and Bacteroides. However, the possible health consequences of such a procedure have not yet been clarified [68].

The gut microbiome can be considered as a whole separate organ of our body. We acquire it at birth, and what it will be like depends on many factors. But one thing is for sure: it will be unlike any other microbiome. This is almost as unique a feature as the papillary lines and vascular pattern of the retina. And just as fingerprints can tell investigators the criminal history of a criminal, the gut microbiome can show scientists the milestones of its host’s ontogenesis. And the process of bacterial colonization and its significance for the body is reflected in the famous proverb: “What you sow, you reap.” Take care of your microbiome and be healthy!

Source: Biomolecule

Picture 8. “Microbial therapy” depending on the stage of the disease. In the preclinical stages, the disease is not yet fully manifested: its symptoms (if any) are minimal and non-specific, but subtle biological changes are already taking place. The use of cultures of certain bacterial communities in the early stages of the disease can prevent dysbiosis and the development of pathology with maximum effectiveness. As the disease progresses, the microbiome is enriched with pathogens (shown in red) that produce pro-inflammatory metabolites and thereby activate inflammatory pathways (Fig. 6). The mucous layer protected by the epithelium becomes thinner as pathogens accumulate, exacerbating the course of the disease. At this stage, diet therapy and antibiotics can be used as a radical measure that changes the quantitative and qualitative composition of bacteria. In the later stages, the continued thinning of the mucous layer allows bacteria to break through the epithelial barrier. Then aggressive antibiotic therapy combined with microbiota transplantation can help restore microbial balance. AMP is a microbial—associated molecular pattern.

However, in young children, prolonged use of antibiotics is fraught with a significant risk of complications. The composition of the microbiota can also be changed through diet therapy by eating foods that promote the growth of “beneficial” microorganisms. One example of such a diet is a special enteral nutrition used for the symptomatic treatment of Crohn’s disease in children. It is a specific mixture of all the necessary micro- and macronutrients and therefore can serve as the only source of nutrients for a long time. It is supplied exclusively in liquid form — orally or through a probe — and contributes to achieving clinical remission by creating a kind of “resting mode”: reducing the functional load on the inflamed intestine and reducing its injury [67].

Research in the field of nutrition deficiency has demonstrated that today it is impossible, using diet therapy alone, to significantly influence the composition of the intestinal microbiome, although the study of the influence of nutrition on it continues.

Given the significant impact on health of the microbiota in early childhood, methods aimed at timely, preventive, restoration of microbial balance look very relevant. Recently, it has been shown that the microbiome of newborns born by caesarean section can be restored to a state similar to babies born naturally. Wiping such children with tampons, which were inserted into the mother’s vagina an hour before cesarean section, led to a significant enrichment of their microbiome with representatives of Lactobacillus and Bacteroides. However, the possible health consequences of such a procedure have not yet been clarified [68].

The gut microbiome can be considered as a whole separate organ of our body. We acquire it at birth, and what it will be like depends on many factors. But one thing is for sure: it will be unlike any other microbiome. This is almost as unique a feature as the papillary lines and vascular pattern of the retina. And just as fingerprints can tell investigators the criminal history of a criminal, the gut microbiome can show scientists the milestones of its host’s ontogenesis. And the process of bacterial colonization and its significance for the body is reflected in the famous proverb: “What you sow, you reap.” Take care of your microbiome and be healthy!

Source: Biomolecule

Published

Июль, 2024

Duration of reading

About 5-6 minutes

Category

Microbiome

Share

List of sources

- Hooper L.V., Littman D.R., Macpherson A.J. (2012). Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 336, 1268–1273;

- Mayer E.A., Knight R., Mazmanian S.K., Cryan J.F., Tillisch K. (2014). Gut microbes and the brain: paradigm shift in neuroscience. J. Neurosci. 34, 15490–15496;

- Rajilic-Stojanovic M., Heilig H.G., Molenaar D., Kajander K., Surakka A., Smidt H., de Vos W.M. (2009). Development and application of the human intestinal tract chip, a phylogenetic microarray: analysis of universally conserved phylotypes in the abundant microbiota of young and elderly adults. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1736–1751;

- Ardissone A.N., de la Cruz D.M., Davis-Richardson A.G., Rechcigl K.T., Li N., Drew J.C. et al. (2014). Meconium microbiome analysis identifies bacteria correlated with premature birth. PLoS One. 9, e90784;

- Moles L., Gomez M., Heilig H., Bustos G., Fuentes S., de Vos W. et al. (2013). Bacterial diversity in meconium of preterm neonates and evolution of their fecal microbiota during the first month of life. PLoS One. 8, e66986;

- Rautava S., Kainonen E., Salminen S., Isolauri E. (2012). Maternal probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and breast-feeding reduces the risk of eczema in the infant. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 130, 1355–1360;

- Dominguez-Bello M.G., Costello E.K., Contreras M., Magris M., Hidalgo G., Fierer N., Knight R. (2010). Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 11971–11975;

- Satokari R., Grönroos T., Laitinen K., Salminen S., Isolauri E. (2009). Bifidobacterium and LactobacillusDNA in the human placenta. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 48, 8–12;

- Aagaard K., Ma J., Antony K.M., Ganu R., Petrosino J., Versalovic J. (2014). The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 237ra265;

- Oh K.J., Lee S.E., Jung H., Kim G., Romero R., Yoon B.H. (2010). Detection of ureaplasmas by the polymerase chain reaction in the amniotic fluid of patients with cervical insufficiency. J. Perinat. Med.38, 261–268;

- DiGiulio D.B., Romero R., Amogan H.P., Kusanovic J.P., Bik E.M., Gotsch F. et al. (2008). Microbial prevalence, diversity and abundance in amniotic fluid during preterm labor: a molecular and culture-based investigation. PLoS One. 3, e3056;

- Jiménez E., Fernández L., Marín M.L., Martín R., Odriozola J.M., Nueno-Palop C. et al. (2005). Isolation of commensal bacteria from umbilical cord blood of healthy neonates born by cesarean section. Curr. Microbiol. 51, 270–274;

- Jimenez E., Marin M.L., Martin R., Odriozola J.M., Olivares M., Xaus J. et al. (2008). Is meconium from healthy newborns actually sterile? Res. Microbiol. 159, 187–193;

- Hu J., Nomura Y., Bashir A., Fernandez-Hernandez H., Itzkowitz S., Pei Z. et al. (2013). Diversified microbiota of meconium is affected by maternal diabetes status. PLoS One. 8, e78257;

- Mackie R.I., Sghir A., Gaskins H.R. (1999). Developmental microbial ecology of the neonatal gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 69, 1035S—1045S;

- Ravel J., Gajer P., Abdo Z., Schneider G.M., Koenig S.S., McCulle S.L. et al. (2011). Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108 Suppl 1, 4680–4687;

- Cohen J. (2016). Vaginal bacteria species can raise HIV infection risk and undermine prevention. Science;

- Witkin S.S. and Ledger W.J. (2012). Complexities of the uniquely human vagina. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 132fs11;

- Backhed F., Roswall J., Peng Y., Feng Q., Jia H., Kovatcheva-Datchary P. et al. (2015). Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 17, 690–703;

- MacIntyre D.A., Chandiramani M., Lee Y.S., Kindinger L., Smith A., Angelopoulos N. et al. (2015). The vaginal microbiome during pregnancy and the postpartum period in a European population. Sci. Rep.5, 8988;

- Insoft R.M., Sanderson I.S., Walker W.A. (1996). Development of immune function within the human intestine and its role in neonatal diseases. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 43, 551–571;

- Jakobsson H.E., Abrahamsson T.R., Jenmalm M.C., Harris K., Quince C., Jernberg C. et al. (2014). Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed Bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced Th1 responses in infants delivered by caesarean section. Gut. 63, 559–566;

- Butte N., Lopez-Alarcon M., Garza C. Nutrient adequacy of exclusive breastfeeding for the term infant during the first six months of life. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. — 47 p.;

- WHO collaborative study team on the role of breastfeeding on the prevention of infant mortality. (2000). Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 355, 451–455;

- Horta B.L. and Victora C.G. Long-term effects of breastfeeding: a systematic review. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. — 69 p.;

- Horta B.L., de Mola C.L., Victora C.G. (2015). Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type-2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 104, 30–37;

- Dorr H. and Sittel I. (1953). Bacteriological examination of human milk and its relation to mastitis. Zentralbl. Gynakol. 75, 1833–1835;

- Martín R., Langa S., Reviriego C., Jimínez E., Marín M.L., Xaus J. et al. (2003). Human milk is a source of lactic acid bacteria for the infant gut. J. Pediatr. 143, 754–758;

- Azad M.B., Konya T., Maughan H., Guttman D.S., Field C.J., Chari R.S. et al. (2013). Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profi les by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months. CMAJ. 185, 385–394;

- Yatsunenko T., Rey F.E., Manary M.J., Trehan I., Dominguez-Bello M.G., Contreras M. et al. (2012). Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 486, 222–227;

- Gura T. (2014). Nature’s fi rst functional food. Science. 345, 747–749;

- De Leoz M.L., Kalanetra K.M., Bokulich N.A., Strum J.S., Underwood M.A., German J.B. et al. (2015). Human milk glycomics and gut microbial genomics in infant feces show a correlation between human milk oligosaccharides and gut microbiota: a proof-of-concept study. J. Proteome Res. 14, 491–502;

- Bourges D., Meurens F., Berri M., Chevaleyre C., Zanello G., Levast B. et al. (2008). New insights into the dual recruitment of IgA+ B cells in the developing mammary gland. Mol. Immunol. 45, 3354–3362;

- Latuga M.S., Stuebe A., Seed P.C. (2014). A review of the source and function of microbiota in breast milk. Semin. Reprod. Med. 32, 68–73;

- Hunt K.M., Foster J.A., Forney L.J., Schutte U.M., Beck D.L., Abdo Z. et al. (2011). Characterization of the diversity and temporal stability of bacterial communities in human milk. PLoS One. 6, e21313;

- Lif Holgerson P., Harnevik L., Hernell O., Tanner A.C., Johansson I. (2011). Mode of birth delivery affects oral microbiota in infants. J. Dent. Res. 90, 1183–1188;

- Cabrera-Rubio R., Collado M.C., Laitinen K., Salminen S., Isolauri E., Mira A. (2012). The human milk microbiome changes over lactation and is shaped by maternal weight and mode of delivery. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 96, 544–551;

- Valles Y., Artacho A., Pascual-Garcia A., Ferrus M.L., Gosalbes M.J., Abellan J.J., Francino M.P. (2014). Microbial succession in the gut: directional trends of taxonomic and functional change in a birth cohort of Spanish infants. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004406;

- Artis D. (2008). Epithelial-cell recognition of commensal bacteria and maintenance of immune homeostasis in the gut. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 411–420;

- McAuley J.L., Linden S.K., Png C.W., King R.M., Pennington H.L., Gendler S.J. et al. (2007). MUC1 cell surface mucin is a critical element of the mucosal barrier to infection. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2313–2324;

- Shen L. and Turner J.R. (2006). Role of epithelial cells in initiation and propagation of intestinal inflammation. Eliminating the static: tight junction dynamics exposed. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver. Physiol. 290, G577–G582;

- Hooper L.V., Wong M.H., Thelin A., Hansson L., Falk P.G., Gordon J.I. (2001). Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 291, 881–884;

- Vijay-Kumar M., Aitken J.D., Carvalho F.A. Cullender T.C., Mwangi S., Srinivasan S. et al. (2010). Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking toll-like receptor 5. Science. 328, 228–231;

- Round J.L. and Mazmanian S.K. (2009). The gut microbiota shapes intestinal responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 313–323;

- O’Hara A.M. and Shanahan F. (2007). Gut microbiota: mining for therapeutic potential. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 274–284;

- Abreu M.T., Fukata M., Arditi M. (2005). TLR signaling in the gut in health and disease. J. Immunol.174, 4453–4460;

- Claud E.C., Lu L., Anton P.M., Savidge T., Walker W.A., Cherayil B.J. (2004). Developmentally-regulated IκB expression in intestinal epithelium and susceptibility to flagellin-induced inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101, 7404–7408;

- Mazmanian S.K. and Kasper D.L. (2006). The love—hate relationship between bacterial polysaccharides and the host immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 849–858;

- Atarashi K., Tanoue T., Shima T., Imaoka A., Kuwahara T., Momose Y. et al. (2011). Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 331, 337–341;

- Зоопарк в моем животе;

- Kozyrskyj A.L., Ernst P., Becker A.B. (2007). Increased risk of childhood asthma from antibiotic use in early life. Chest. 131, 1753–1759;

- Risnes K.R., Belanger K., Murk W., Bracken M.B. (2011). Antibiotic exposure by 6 months, and asthma and allergy at 6 years: findings in a cohort of 1,401 US children. Am. J. Epidemiol. 173, 310–318;

- Hoskin-Parr L., Teyhan A., Blocker A., Henderson A.J. (2013). Antibiotic exposure in the first 2 years of life and development of asthma and other allergic diseases by 7.5 years: a dose-dependent relationship. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 24, 762–771;

- Bailey L.C., Forrest C.B., Zhang P., Richards T.M., Livshits A., DeRusso P.A. (2014). Association of antibiotics in infancy with early childhood obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 168, 1063–1069;

- Metsälä J., Lundqvist A., Virta L.J., Kaila M., Gissler M., Virtanen S.M. (2013). Mother’s and offspring’s use of antibiotics, and infant allergy to cow’s milk. Epidemiology. 24, 303–309;

- Kronman M.P., Zaoutis T.E., Haynes K., Feng R., Coffin S.E. (2012). Antibiotic exposure and IBD development among children: a population-based cohort study. Pediatrics. 130, e794–e803;

- Braegger C., Chmielewska A., Decsi T., Kolacek S., Mihatsch W., Moreno L. et al. (2011). Supplementation of infant formula with probiotics and/or prebiotics: a systematic review and comment by the ESPGHAN committee on nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 52, 238–250;

- Panduru M., Panduru N.M., Sălăvăstru C.M., Tiplica G.S. (2015). Probiotics and primary prevention of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 29, 232–242;

- Foolad N., Brezinski E.A., Chase E.P., Armstrong A.W. (2013). Effect of nutrient supplementation on atopic dermatitis in children: a systematic review of probiotics, prebiotics, formula and fatty acids. JAMA Dermatol. 149, 350–355;

- Doege K., Grajecki D., Zyriax B.C., Detinkina E., Zu Eulenburg C., Buhling K.J. (2012). Impact of maternal supplementation with probiotics during pregnancy on atopic eczema in childhood — a meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 107, 1–6;

- Kim S.O., Ah Y.M., Yu Y.M., Choi K.H., Shin W.G., Lee J.Y. (2014). Effects of probiotics for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 113, 217–226;

- Savino F., Cordisco L., Tarasco V., Palumeri E., Calabrese R., Oggero R. et al. (2010). Lactobacillus reuteriDSM 17938 in infantile colic: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 126, e526–e533;

- Song S.J., Lauber C., Costello E.K., Lozupone C.A., Humphrey G., Berg-Lyons D. et al. (2013). Cohabiting family members share microbiota with one another and with their dogs. Elife. 2, e00458;

- Sjögren Y.M., Jenmalm M.C., Böttcher M.F., Björkstén B., Sverremark-Ekström E. (2009). Altered early infant gut microbiota in children developing allergy up to 5 years of age. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 39, 518–526;

- Ownby D.R., Johnson C.C., Peterson E.L. (2002). Exposure to dogs and cats in the first year of life and risk of allergic sensitization at 6 to 7 years of age. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 288, 963–972;

- Normand A.C., Sudre B., Vacheyrou M., Depner M., Wouters I.M., Noss I. et al. (2011). Airborne cultivable microflora and microbial transfer in farm buildings and rural dwellings. Occup. Environ. Med. 68, 849–855;

- Ткаченко Е.И., Иванов С.В., Жигалова Т.Н., Ситкин С.И. (2008). Энтеральное питание при язвенном колите. Лечащий Врач. 6;

- Dominguez-Bello M.G., De Jesus-Laboy K.M., Shen N., Cox L.M., Amir A., Gonzalez A. et al. (2016). Partial restoration of the microbiota of cesarean-born infants via vaginal microbial transfer. Nat. Med.22, 250–253;

- Nuriel-Ohayon M., Neuman H., Koren O. (2016). Microbial changes during pregnancy, birth, and infancy. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1031;

- Newburg D.S. and Morelli L. (2015). Human milk and infant intestinal mucosal glycans guide succession of the neonatal intestinal microbiota. Pediatr. Res. 77, 115–120;

- Tamburini S., Shen N., Wu H.C., Clemente J.C. (2016). The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat. Med. 22, 713–722.