What do microbes want from us?

Recently, another article was published in the journal Nature, blaming a number of human diseases, including mental ones, on the microbes that inhabit our intestines. For half a century of studying intestinal bacteria, scientists have not been able to determine which they bring more benefit or harm. But we managed to make sure that, among other things, microbes can change human behavior and mental health. We translate their signals from microbial language into human language and invite the reader to decide for himself whether bacteria are our friends or enemies (but we do not promise that they will not influence his opinion).

About germs and people

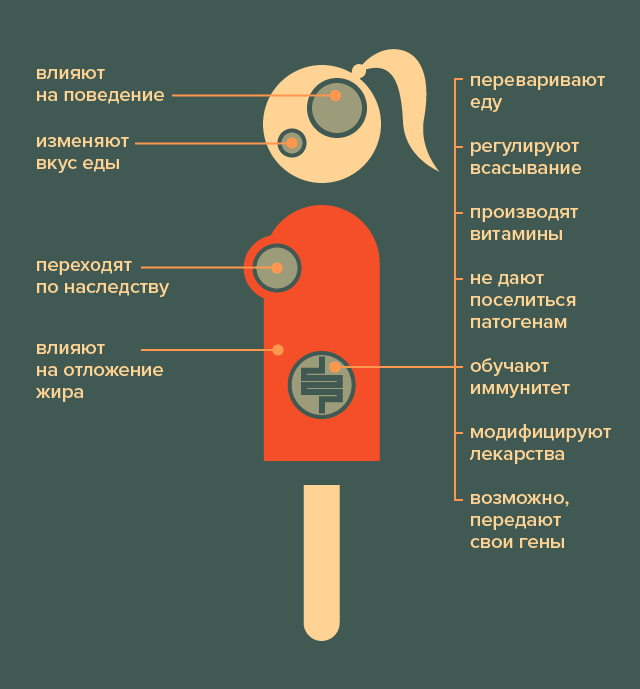

Picture 1. What are microbes doing in the human body? Upon closer examination, it turns out that they affect almost all aspects of the body’s vital activity. [21]

It turns out, on the one hand, that danger is always nearby. On the other hand, it is impossible to get rid of it, because the absence of microbes has even worse consequences than their presence. For example, according to the “hygienic hypothesis”, excessive striving for cleanliness and hygiene is harmful to health, and early contact of a child with bacteria and allergens, on the contrary, strengthens the immune system [2]. However, there are still articles published, the authors of which consider microbes as parasites that use humans for their own needs [3]. And here the influence of the microbiota on the human nervous system becomes a strong argument.

The path to the brain is through the stomach

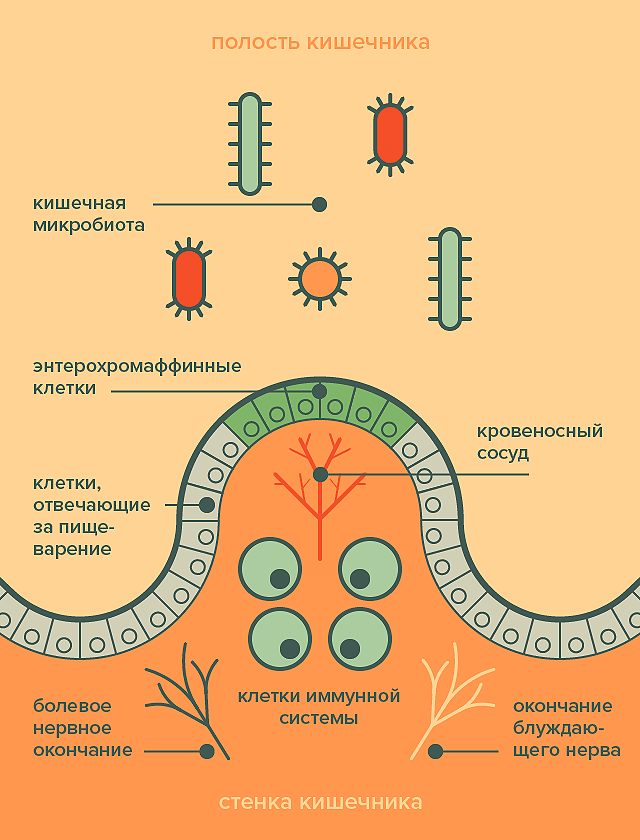

It would seem that where is the brain, and where is the stomach? Nevertheless, the first thing that the body needs for survival is food, which means that the brain must clearly understand whether it is there, what is happening with it, and whether the digestive system is working well. Specifically for this purpose, enterochromaffin cells, microeles, are located in the intestinal wall, secreting many regulatory substances (Pic. 2). Some of them act on nearby cells, stimulating or slowing down digestion. Others activate neurons in the intestinal wall, in particular, the endings of the vagus nerve, which goes directly to the brain. In addition, there are painful endings under the surface of the intestine, which also react to substances released by enterochromaffin cells, and may signal that the body has eaten something wrong. Finally, the intestinal wall is populated with immune cells that are sensitive to the substances that penetrate inside. When an enemy is detected, these cells trigger inflammation, releasing substances that act on nerve endings and enter the bloodstream. Thus, stress can turn from local to global [9].

Information about the activity of bacteria also, of course, quickly ends up in the brain. Firstly, “peaceful” microbes stimulate digestion, and a lot of digested or synthesized foods enter the bloodstream. For example, short-chain fatty acids (by breaking them down, we get 5-10% of our daily energy). There are receptors on brain cells that catch them and signal a feeling of fullness. In addition, the brain develops better when energy resources are available. Children who experienced a lack of food in the womb are more likely to develop schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. An increase in the amount of short-chain fatty acids in the blood, on the contrary, stimulates learning and memory [10].

Secondly, bacteria actively communicate with the intestinal wall (and through it with the host’s brain), releasing substances that act on enterochromaffin cells. Interestingly, the signaling substances of bacteria are simply direct analogues of our own hormones and neurotransmitters: it turned out that the intestinal microflora can produce norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, testosterone, histamine, as well as the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid and appetite-regulating proteins (for example, ghrelin and leptin) [3], [11], [12]. Moreover, some bacteria can secrete benzodiazepines, substances that have a calming effect [13] (among their relatives, for example, the well—known tranquilizer phenazepam). Scientists believe that all these signaling molecules are very ancient and were used by bacteria to communicate with each other back in the days when multicellular organisms were just developing [14]. That is, the intestinal microflora acts as an additional gland in the human body.

Picture 1. What are microbes doing in the human body? Upon closer examination, it turns out that they affect almost all aspects of the body’s vital activity. [21]

It turns out, on the one hand, that danger is always nearby. On the other hand, it is impossible to get rid of it, because the absence of microbes has even worse consequences than their presence. For example, according to the “hygienic hypothesis”, excessive striving for cleanliness and hygiene is harmful to health, and early contact of a child with bacteria and allergens, on the contrary, strengthens the immune system [2]. However, there are still articles published, the authors of which consider microbes as parasites that use humans for their own needs [3]. And here the influence of the microbiota on the human nervous system becomes a strong argument.

The path to the brain is through the stomach

It would seem that where is the brain, and where is the stomach? Nevertheless, the first thing that the body needs for survival is food, which means that the brain must clearly understand whether it is there, what is happening with it, and whether the digestive system is working well. Specifically for this purpose, enterochromaffin cells, microeles, are located in the intestinal wall, secreting many regulatory substances (Pic. 2). Some of them act on nearby cells, stimulating or slowing down digestion. Others activate neurons in the intestinal wall, in particular, the endings of the vagus nerve, which goes directly to the brain. In addition, there are painful endings under the surface of the intestine, which also react to substances released by enterochromaffin cells, and may signal that the body has eaten something wrong. Finally, the intestinal wall is populated with immune cells that are sensitive to the substances that penetrate inside. When an enemy is detected, these cells trigger inflammation, releasing substances that act on nerve endings and enter the bloodstream. Thus, stress can turn from local to global [9].

Information about the activity of bacteria also, of course, quickly ends up in the brain. Firstly, “peaceful” microbes stimulate digestion, and a lot of digested or synthesized foods enter the bloodstream. For example, short-chain fatty acids (by breaking them down, we get 5-10% of our daily energy). There are receptors on brain cells that catch them and signal a feeling of fullness. In addition, the brain develops better when energy resources are available. Children who experienced a lack of food in the womb are more likely to develop schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. An increase in the amount of short-chain fatty acids in the blood, on the contrary, stimulates learning and memory [10].

Secondly, bacteria actively communicate with the intestinal wall (and through it with the host’s brain), releasing substances that act on enterochromaffin cells. Interestingly, the signaling substances of bacteria are simply direct analogues of our own hormones and neurotransmitters: it turned out that the intestinal microflora can produce norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, testosterone, histamine, as well as the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid and appetite-regulating proteins (for example, ghrelin and leptin) [3], [11], [12]. Moreover, some bacteria can secrete benzodiazepines, substances that have a calming effect [13] (among their relatives, for example, the well—known tranquilizer phenazepam). Scientists believe that all these signaling molecules are very ancient and were used by bacteria to communicate with each other back in the days when multicellular organisms were just developing [14]. That is, the intestinal microflora acts as an additional gland in the human body.

Picture 2. The intestinal wall is an intermediary between the microflora on the one hand and the nervous and immune systems on the other. [21]

So what do microbes want?

To a first approximation, the motivation of microbes is simple: They want food. If there are not enough nutrients, they can release substances that stimulate pain endings in the intestinal wall. There is even a frightening hypothesis that colic in infants is also caused by bacteria: pain causes the body to redirect internal energy resources to the intestinal area, and crying (caused by the action of microbes on the brain) attracts parents who try to feed the child to calm [3].

If the owner is old enough, then it is possible to regulate the extraction of food directly through his nervous system. For example, with enough food, some of our beneficial neighbors synthesize the essential amino acid tryptophan, on the basis of which our body produces serotonin, the so-called “hormone of happiness.” Serotonin, in turn, regulates the activity of the nervous system, causing a feeling of satiety, calmness and joy. When there is a lack of food, microbial hormones and neurotransmitters can shift behavior towards anxiety and search behavior. In a well-known experiment, scientists transplanted microflora from a line of mice with increased anxiety to ordinary mice, and their anxiety level also increased [15]. Microbiota features have also been found in people with behavioral disorders, such as those suffering from depression, schizophrenia, and anorexia. Scientists believe that the cause of these disorders may be an imbalance of neurotransmitters caused by intestinal bacteria [16].

Besides, microbes want their favorite food. The microbiota consists of many types of bacteria that vary in their dietary preferences. And each type of bacteria tends to act on the host’s body in such a way that it eats their favorite substances more often. This is probably why the composition of the intestinal microflora differs among people who follow different diets: the dominant microbes cause cravings for different types of food. They can achieve this, for example, by redistributing taste buds. It is known that the sense of taste can change during intestinal surgery, during which the microbial composition inevitably changes. But even for those who follow the same diet, bacteria can cause a shift in food preferences. Scientists compared the content of bacterial substances in the urine of people with a sweet tooth and people who were indifferent to sweets, who nevertheless ate the same way. It turned out that these substances in the urine are different! It turns out that sugar cravings may be a property of the microflora, not its host. So if it seems to you that you are pathologically fond of chocolate, then it is possible that your microbes actually adore it [3].

Finally, microbes want to travel, enter other organisms, and exchange genes with distant relatives living with other hosts. Therefore, it would be beneficial for them to increase a person’s sociality. Indeed, it was found that mice raised in a microbial environment exhibit behavioral features similar to those of autistic people because they do not receive an internal socializing signal [10]. Scientists have also identified differences between the microbiota of children with autism spectrum disorders and healthy children. At the same time, most autistic children limit their diet to a small range of foods. It is believed that this is due to an imbalance of their microflora: some microbes are numerous, others are almost nonexistent, so taste preferences are strongly biased, and there are not enough calls for sociality from bacteria [17].

Contagious appetite

So, many features or behavioral disorders may be bacterial in nature. This leads to two conclusions that are likely to influence the medicine of the future.

Picture 2. The intestinal wall is an intermediary between the microflora on the one hand and the nervous and immune systems on the other. [21]

So what do microbes want?

To a first approximation, the motivation of microbes is simple: They want food. If there are not enough nutrients, they can release substances that stimulate pain endings in the intestinal wall. There is even a frightening hypothesis that colic in infants is also caused by bacteria: pain causes the body to redirect internal energy resources to the intestinal area, and crying (caused by the action of microbes on the brain) attracts parents who try to feed the child to calm [3].

If the owner is old enough, then it is possible to regulate the extraction of food directly through his nervous system. For example, with enough food, some of our beneficial neighbors synthesize the essential amino acid tryptophan, on the basis of which our body produces serotonin, the so-called “hormone of happiness.” Serotonin, in turn, regulates the activity of the nervous system, causing a feeling of satiety, calmness and joy. When there is a lack of food, microbial hormones and neurotransmitters can shift behavior towards anxiety and search behavior. In a well-known experiment, scientists transplanted microflora from a line of mice with increased anxiety to ordinary mice, and their anxiety level also increased [15]. Microbiota features have also been found in people with behavioral disorders, such as those suffering from depression, schizophrenia, and anorexia. Scientists believe that the cause of these disorders may be an imbalance of neurotransmitters caused by intestinal bacteria [16].

Besides, microbes want their favorite food. The microbiota consists of many types of bacteria that vary in their dietary preferences. And each type of bacteria tends to act on the host’s body in such a way that it eats their favorite substances more often. This is probably why the composition of the intestinal microflora differs among people who follow different diets: the dominant microbes cause cravings for different types of food. They can achieve this, for example, by redistributing taste buds. It is known that the sense of taste can change during intestinal surgery, during which the microbial composition inevitably changes. But even for those who follow the same diet, bacteria can cause a shift in food preferences. Scientists compared the content of bacterial substances in the urine of people with a sweet tooth and people who were indifferent to sweets, who nevertheless ate the same way. It turned out that these substances in the urine are different! It turns out that sugar cravings may be a property of the microflora, not its host. So if it seems to you that you are pathologically fond of chocolate, then it is possible that your microbes actually adore it [3].

Finally, microbes want to travel, enter other organisms, and exchange genes with distant relatives living with other hosts. Therefore, it would be beneficial for them to increase a person’s sociality. Indeed, it was found that mice raised in a microbial environment exhibit behavioral features similar to those of autistic people because they do not receive an internal socializing signal [10]. Scientists have also identified differences between the microbiota of children with autism spectrum disorders and healthy children. At the same time, most autistic children limit their diet to a small range of foods. It is believed that this is due to an imbalance of their microflora: some microbes are numerous, others are almost nonexistent, so taste preferences are strongly biased, and there are not enough calls for sociality from bacteria [17].

Contagious appetite

So, many features or behavioral disorders may be bacterial in nature. This leads to two conclusions that are likely to influence the medicine of the future.

- Behavioral patterns can be transmitted through microbes. This is supported by an experiment with mice in which microflora transplantation changed their behavior towards a more alarming one. In addition, scientists have calculated that people who have close friends who are obese have an increased risk of developing the same symptom. It is possible that the tendency to obesity can also be transmitted along with microbes, although this has not yet been directly proven. Finally, there is a hypothesis that taste preferences (which, as we already know, can also change under the influence of bacteria) are closer among members of the same family than among unfamiliar people. This probably allows us to reveal the “secret of mom’s borscht” — food cooked at home may seem tastier than others, not only because a person gets used to it from childhood, but also because his relatives have the closest composition of bacteria to him, which require the same nutrients [3].

- Behavioral patterns can be treated with microbes. More and more diseases are associated with differences in the intestinal microbiota. For example, scientists have recently been able to distinguish people suffering from depression from healthy people in 100% of cases using only stool analysis [18]. And when the cause becomes known, treatment opportunities open up. And despite the fact that a generally available microbial therapy has not yet been developed, individual studies show amazing results. For example, depression was cured more successfully when antidepressants were combined with antibiotics (which destroy excess intestinal inhabitants) [19]. And fecal transplants (complex procedures in which bacteria are extracted from the stool of healthy people, packaged in capsules and fed to patients) have reduced the severity of autism symptoms in humans [20]. Finally, microbial prevention also bore fruit: among the group of children who were regularly fed probiotics (with a set of microbes from the “normal” microflora), none developed either Asperger’s syndrome or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, while in the control group 17% of children grew up with one of these behavioral disorders. deviations [20].

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Published

July, 2024

Duration of reading

About 3-4 minutes

Category

Microbiome

Share

List of sources

- The Gut Microbiome: The world inside us;

- Old friends are the key to autoimmune diseases;

- Joe Alcock, Carlo C. Maley, C. Athena Aktipis. (2014). Is eating behavior manipulated by the gastrointestinal microbiota? Evolutionary pressures and potential mechanisms. BioEssays. 36, 940-949;

- Why is it so difficult to lose weight, or the Effect of the gut microbiota on metabolism;

- New functions of the intestinal microflora;

- Reardon S. (2017). Gut bacteria can stop cancer drugs from working. Nature News;

- J. C. D. Hotopp, M. E. Clark, D. C. S. G. Oliveira, J. M. Foster, P. Fischer, et. al.. (2007). Widespread Lateral Gene Transfer from Intracellular Bacteria to Multicellular Eukaryotes. Science. 317, 1753-1756;

- Cédric Feschotte. (2004). Merlin, a New Superfamily of DNA Transposons Identified in Diverse Animal Genomes and Related to Bacterial IS1016 Insertion Sequences. Unknown journal title.. 21, 1769-1780;

- Sang H. Rhee, Charalabos Pothoulakis, Emeran A. Mayer. (2009). Principles and clinical implications of the brain–gut–enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6, 306-314;

- Joel Selkrig, Peiyan Wong, Xiaodong Zhang, Sven Pettersson. (2014). Metabolic tinkering by the gut microbiome. Gut Microbes. 5, 369-380;

- Serotonin networks;

- Calm as GABA;

- A Brief History of antidepressants;

- Lakshminarayan M. Iyer, L. Aravind, Steven L. Coon, David C. Klein, Eugene V. Koonin. (2004). Evolution of cell–cell signaling in animals: did late horizontal gene transfer from bacteria have a role?. Trends in Genetics. 20, 292-299;

- Premysl Bercik, Emmanuel Denou, Josh Collins, Wendy Jackson, Jun Lu, et. al.. (2011). The Intestinal Microbiota Affect Central Levels of Brain-Derived Neurotropic Factor and Behavior in Mice. Gastroenterology. 141, 599-609.e3;

- Emily Deans. (2017). Microbiome and mental health in the modern environment. J Physiol Anthropol. 36;

- Jennifer G. Mulle, William G. Sharp, Joseph F. Cubells. (2013). The Gut Microbiome: A New Frontier in Autism Research. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 15;

- A. Naseribafrouei, K. Hestad, E. Avershina, M. Sekelja, A. Linløkken, et. al.. (2014). Correlation between the human fecal microbiota and depression. Neurogastroenterol. Motil.. 26, 1155-1162;

- Tsuyoshi Miyaoka, Rei Wake, Motohide Furuya, Kristian Liaury, Masa Ieda, et. al.. (2012). Minocycline as adjunctive therapy for patients with unipolar psychotic depression: An open-label study. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 37, 222-226;

- Dae-Wook Kang, James B. Adams, Ann C. Gregory, Thomas Borody, Lauren Chittick, et. al.. (2017). Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome. 5;

- Loseva P. (2017). What do microbes want from us? “The Attic”.