Who is parasitizing on parasites?

The abundance of bacteriophages in the human microbiome has received its own name — “phage”. Scientists have long wondered exactly how phages affect and possibly even control the human immune system. Jeremy Barr, who studies bacteriophages in At Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, he led a team of scientists who

published the results of his work in

mBio. “It is generally assumed that phages do not interact with eukaryotic cells, but this assumption is erroneous,” he says.

For decades, doctors have been predictably trying to turn bacterial parasites into antibiotics. This technique has indeed achieved some success, but phage therapy has not been widely used.

Barr’s previous research has shown that phages can naturally protect our bodies from pathogens. After studying a wide range of living creatures, from corals to humans, he found that phages secrete four times more mucus than those microorganisms that protect our gums and intestines, if placed in a similar environment. It turned out that the protein shell of bacteriophages can bind mucins (large secreted molecules) to water, thereby forming a protective mucous layer. Such measures are equally useful for both the phages themselves and the animals in which they live. Mucus is not only a good protection against aggressive environmental conditions for our cells, but also an environment in which phages can hunt quickly and efficiently.

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox

Phagome: a unique human microbiome

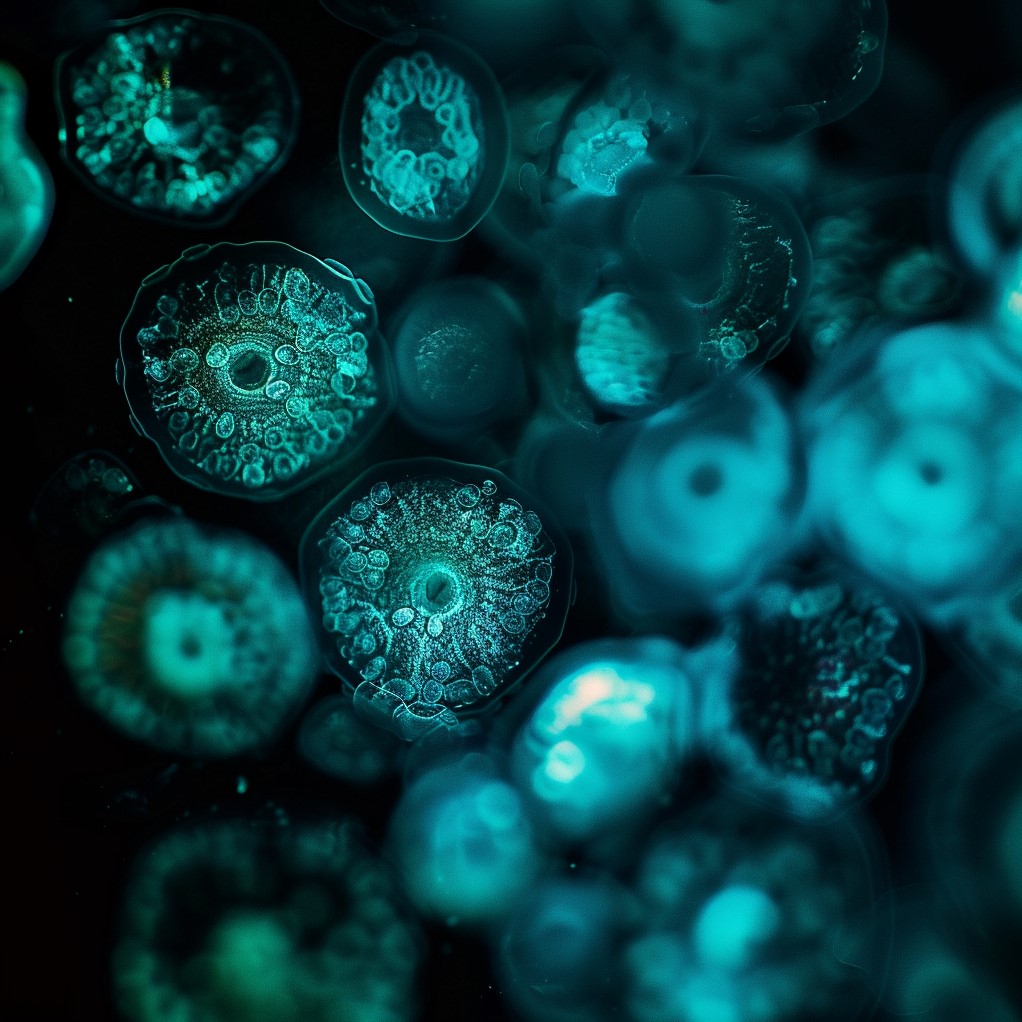

The contents of each phage are protected by a protein capsule, which also helps form a protective layer of mucus on the human epithelium.

Researchers have now published evidence that bacteriophage viruses can enter the human body through the stomach. The epithelium lining the stomach and other organs captured viral particles and sent them on a journey throughout the body. Moreover, epithelial cells sequentially captured phages that lived on the outside of the body (for example, in the intestinal lumen) and transported them to the inside, which requires additional protection. The transport mechanism is still unknown, but, apparently, phages travel in microbubbles, the so-called vesicles.

It is worth noting that all the studies were conducted in vitro, so the behavior of phages in the human body may differ slightly from the demonstrated results. In addition, Barro’s team used cancer cells, which can more or less effectively absorb phage particles in comparison with healthy ones.

But what happens when bacteriophages enter our tissues? In 2004, a research group led by Kristina Dabrowska from the Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Wroclaw reported that certain types of phages could fuse cancer cell membranes, reducing tumor growth during laboratory tests on mice. A few years later, another phage expert, Andrzej Gorski, demonstrated that phages can also affect the immune system of mice by slowing down the proliferation of T cells and the production of antibodies. In other words, if used correctly, bacteriophages can prevent the body’s own immune system from attacking the transplanted tissues.

Moreover, Barr believes that a steady influx of phages can create an “intragenic phagome” that can modulate the immune response. This theory is supported by a study published this year by a group of Belgian scientists. Its essence is as follows: white blood cells taken from healthy people were exposed to five different types of phages. In the process, it turned out that the cells produce mainly immune molecules, which, for example, reduce the symptoms of colds and suppress inflammation. Another work supports Barr’s theory: a group led by immunologist Herbert David at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, found that intestinal phagomes changed in people with two autoimmune conditions, type I diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that most of the disparate studies have yet to be combined into a common method of phage therapy, the potential of the latter is noticeable to the naked eye. Barr continues to think about how the phage can warn the human immune system about the invasion of potential pathogens: for example, bacteria can bring on themselves a new “portion” of phages that somehow respond to the body’s response in the form of inflammatory reactions.

Once scientists fully understand and study the role of the human phagome in daily life, it can be used even for pinpoint manipulation of bacterial colonies inside our body. Moreover, one day they may even become a tool for controlling the cellular structures of the person himself.