Platform viruses: Poison for good

The term “virus” in Latin means “poison”. The mere mention of this word is enough to frighten a person inexperienced in biology. Indeed, these tiny creatures excite the consciousness of many inhabitants of our planet every day. And for good reason: more than 250,000 people die from various forms of the influenza virus in the world every year, and more than a million people die from AIDS. Unfortunately, this stereotype of fear of viruses has developed among the world’s population for a long time and is unlikely to ever disappear. This article is intended to prove that “the virus is not as terrible as it is painted.” Moreover, the emphasis is on a specific aspect of this problem: the use of viruses as matrices (platforms) to create fundamentally new materials. In other words, we are talking about viral nanotechnology.

About nanotechnology (as an introduction)

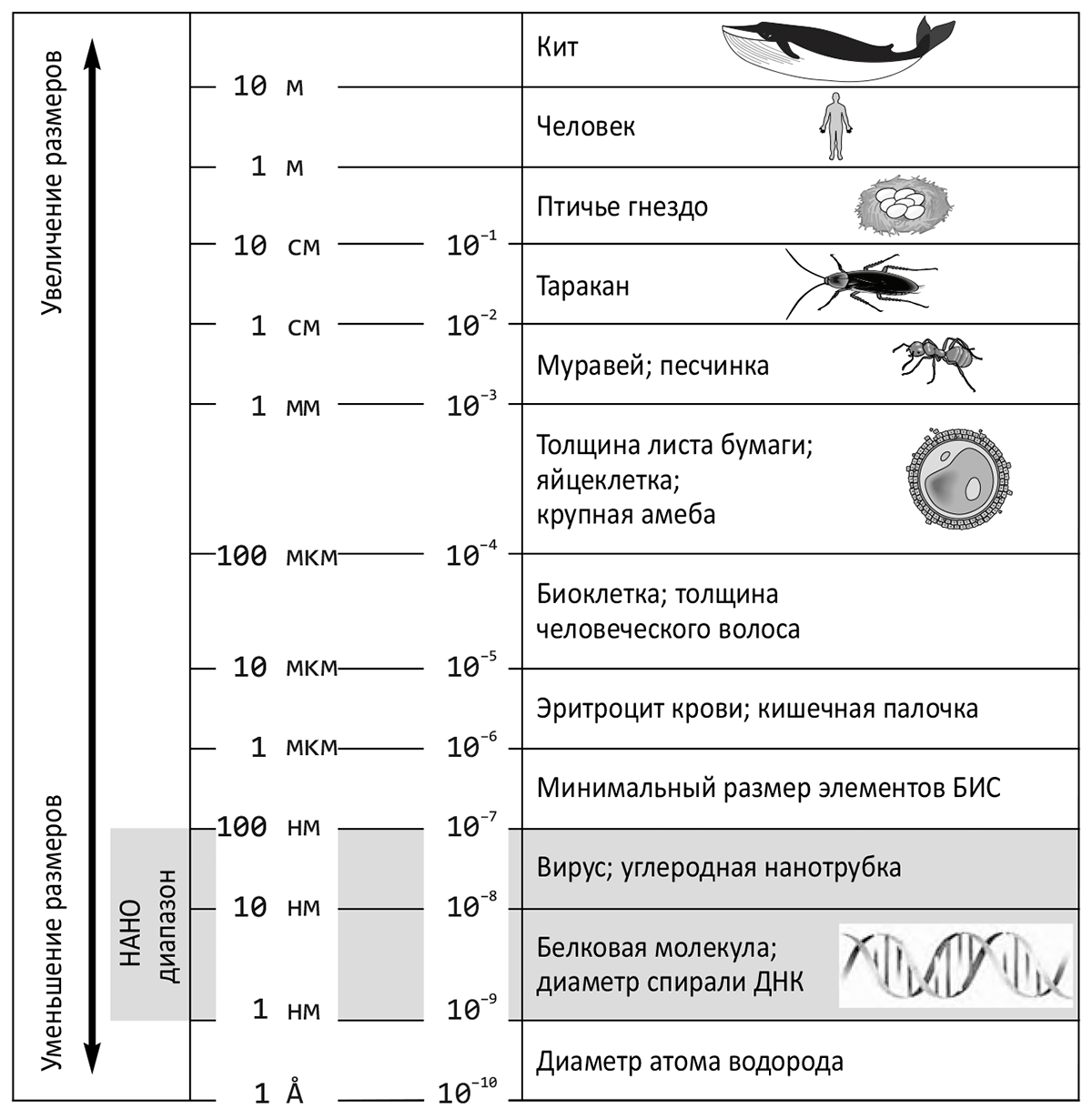

Most modern (and not so modern) books, reviews, articles, and even news that mention the word “nanotechnology” begin with an interpretation (which, generally speaking, is a wagon and a small cart) and the history of the term. I will not deviate from this principle and will say a few words about this field of science. Despite the fact that the birth of this term is usually associated with the name of a famous physicist. Richard Feynman (who also had a passion for biological research), namely with his speech “There’s Plenty of Room at The Bottom: An Invitation to Enter a New Field of Physics” (“There’s plenty of room down there: an invitation to a new World of physics”) at the American Physical Society Christmas dinner on December 29, 1959 In fact, the word was first used by Japanese physicist Norio Taniguchi in 1974 in reference to submicron structures (i.e., with sizes of fractions of a micron or less). [1]: Nanotechnology is derived from the Greek words vανος (dwarf), τεχνη (art) and λογος (teaching). — creation and use of materials, devices and systems, the structure of which is implemented in the nanometer range (from fractions of a nanometer to 100 nm). It should be noted that one nanometer, equal to 10-9 meters, is practically comparable to the diameter of a hydrogen atom — about 1 Å (1 angstrom = 10-10 meters). In other words, nanotechnology actually operates with atomic and molecular structures. In Fig. 1 shows a dimensional hierarchy, which shows how small this nanoscale range seems to us, macroscopic creatures, despite its richness and beauty. The prefixes “nano-” and “bio-” are inextricably linked, especially when it comes to molecular and cellular biology, virology, genetics, biochemistry, etc. Biomolecules, viruses, cellular organelles, and other supramolecular biostructures can thus be considered objects of nanotechnology [3]. Picture 1. The place of nanoscale objects in the world around us. From the book “Introduction to Nanotechnology” by Japanese nanotechnologist Naoya Kobayashi [2].

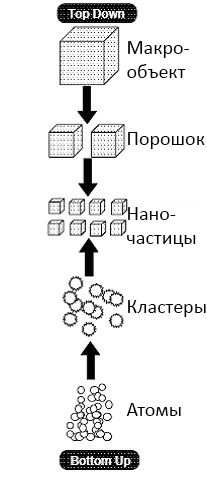

In nanotechnology, there are two main approaches to the creation of nanomaterials and nanostructures: from top to bottom (top–down) and bottom–up (bottom-up) (fig. 2). The first group of methods aims to split or sequentially cut (disperse) the source material to produce nanoscale particles from it. The second approach is designed, on the contrary, to “build” nanostructures sequentially, like a building, starting from the foundation: atom by atom, molecule by molecule, cluster by cluster.

Picture 1. The place of nanoscale objects in the world around us. From the book “Introduction to Nanotechnology” by Japanese nanotechnologist Naoya Kobayashi [2].

In nanotechnology, there are two main approaches to the creation of nanomaterials and nanostructures: from top to bottom (top–down) and bottom–up (bottom-up) (fig. 2). The first group of methods aims to split or sequentially cut (disperse) the source material to produce nanoscale particles from it. The second approach is designed, on the contrary, to “build” nanostructures sequentially, like a building, starting from the foundation: atom by atom, molecule by molecule, cluster by cluster.

Picture 2. A top-down and bottom-up nanostructure construction scheme. Picture: S.D. Suneel, “Nanotechnology“.

For the first time, the famous American nanotechnologist drew attention to the bottom-up strategy Eric Drexler, who published his first book “Creation Machines: the Advent of the Era of Nanotechnology” in 1986. In contrast to the traditional top-down technological approach, Drexler emphasized the importance of the bottom-up principle, referring to atomic and molecular assembly.

Again, returning to biology, it is necessary to mention such important properties of biopolymers and supramolecular structures as the ability, under certain conditions, to spontaneously and reversibly assemble into molecular complexes (self-assembly). Viral particles are also capable of self-assembly. That is, bionic nanoparticles can be formed under different circumstances both on the top-down principle and on the bottom-up principle. But in nature, unlike human technology, the small-to-large method is more natural and traditional. The assembly of biostructures is often based not on the initial molecular matrices, but on the processes of self-organization.

Picture 2. A top-down and bottom-up nanostructure construction scheme. Picture: S.D. Suneel, “Nanotechnology“.

For the first time, the famous American nanotechnologist drew attention to the bottom-up strategy Eric Drexler, who published his first book “Creation Machines: the Advent of the Era of Nanotechnology” in 1986. In contrast to the traditional top-down technological approach, Drexler emphasized the importance of the bottom-up principle, referring to atomic and molecular assembly.

Again, returning to biology, it is necessary to mention such important properties of biopolymers and supramolecular structures as the ability, under certain conditions, to spontaneously and reversibly assemble into molecular complexes (self-assembly). Viral particles are also capable of self-assembly. That is, bionic nanoparticles can be formed under different circumstances both on the top-down principle and on the bottom-up principle. But in nature, unlike human technology, the small-to-large method is more natural and traditional. The assembly of biostructures is often based not on the initial molecular matrices, but on the processes of self-organization.

“Nanobio-” and “bionano-” — feel the difference!

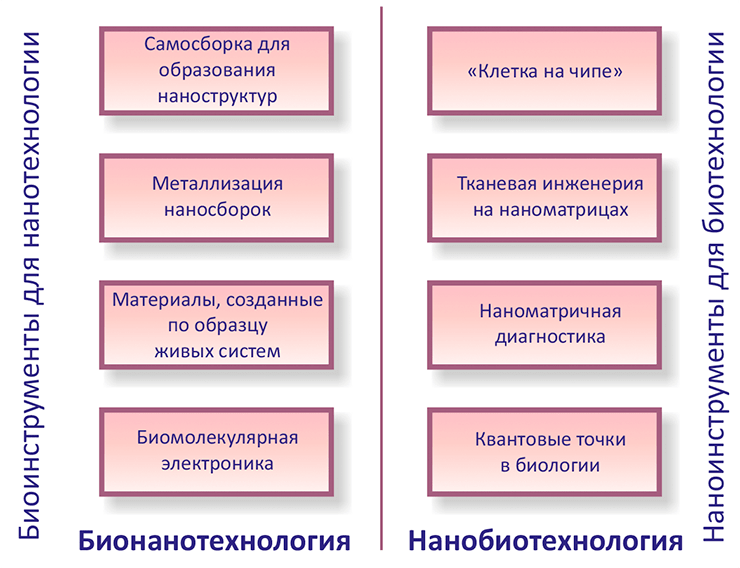

Now that the path from nanotechnology to nanobiology has been outlined, some terminological nuances in this field of nanotechnology should be discussed. Many modern biologists often use the words “nanobiotechnology” and “bionanotechnology.” Meanwhile, the difference between them has recently become more and more noticeable. Picture 3. That’s what nanobio- and bionanotechnology is for. From the review book by Ehud Gazit, a specialist in nanobiology from Israel, “Nanobiotechnology: Vast development prospects” [5].

Nanobiotechnology should be understood as the use of nanotechnology techniques for the development and improvement of biotechnological methods and products. This field includes, for example, nanosensors [4] operating in real time, nanoscale matrices for controlling drug production, tissue engineering and tissue repair, and nanorobots.

Bionanotechnology is the use of biological building blocks, as well as biological specificity and activity in developing nanotechnology. In the future, bionanotechnology will allow, for example, to modify DNA, proteins, etc. for the needs of nanoelectronics and nanoelectrochemistry.

In other words, nanobiotechnology is the use of nanoscience to solve biological problems, and bionanotechnology involves the use of biological assemblies to solve a variety of problems (Pic. 3).

Picture 3. That’s what nanobio- and bionanotechnology is for. From the review book by Ehud Gazit, a specialist in nanobiology from Israel, “Nanobiotechnology: Vast development prospects” [5].

Nanobiotechnology should be understood as the use of nanotechnology techniques for the development and improvement of biotechnological methods and products. This field includes, for example, nanosensors [4] operating in real time, nanoscale matrices for controlling drug production, tissue engineering and tissue repair, and nanorobots.

Bionanotechnology is the use of biological building blocks, as well as biological specificity and activity in developing nanotechnology. In the future, bionanotechnology will allow, for example, to modify DNA, proteins, etc. for the needs of nanoelectronics and nanoelectrochemistry.

In other words, nanobiotechnology is the use of nanoscience to solve biological problems, and bionanotechnology involves the use of biological assemblies to solve a variety of problems (Pic. 3).

A guest from the nanomir: small, but dashing!

It’s time to talk about viruses. Now the word “virus” is widely heard, but the associations are different: infection, flu, Arbidol advertising, AIDS, Kaspersky anti-virus, “am I really sick!!!”, a non-cellular form of life… I don’t think there are many people on the street who would use the term “virus” to evoke positive emotions. However, I will try to convince as many people as possible that the virus is not so terrible and that it can become a loyal ally in the fight against a huge number of human problems, including medical ones. But more on that later. Now there is a little information about these creatures (I will not talk about the infection process, because it is written in great detail in many textbooks and on the Internet). Viruses are submicroscopic (20-400+ nm in diameter) non-cellular objects whose genomes consist of nucleic acid and which replicate in living cells. Using their (cells’) synthetic apparatus, they cause the synthesis of specialized structures capable of transferring the viral genome to other cells. Despite the “non-cellular nature”, the existence of viruses does not contradict the postulate of cellular theory (which is still relevant) “There is no life outside the cell,” because they cannot reproduce without entering a living cell. Viruses have a wide variety of nucleic acids. This fact is embedded in the classification, first proposed by an American biologist, a Nobel Prize winner by David Baltimore in 1971. At the center of this classification is viral informational, or matrix, RNA (mRNA), to which Baltimore attributed a positive (+) polarity. Positive nucleic acids also include RNA and DNA with mRNA polarity. The complementary mRNA chains have a negative polarity (−). As a result, Baltimore divided the viruses into six classes. Later, in 1974, this system was modified by Vadim Israilevich Agol, a professor at the Department of Virology at the Faculty of Biology of Moscow State University [6]. The main “innovation” in the Baltimore classification are DNA viruses with the stage of DNA synthesis on an RNA matrix in their cycle (retroid viruses, or para-retroviruses, including the famous hepatitis B virus). And that’s what happened (Pic. 4). Picture 4. Classification of viruses according to V.I. Agol. Gray arrows — replication, pink — transcription, gray-black — reverse transcription of retro- and retroid viruses; pink font — intermediates (intermediates), black font in a frame — viral genomes; cDNA — single-stranded DNA. The scheme from the magazine “Nature”, № 9 (2009) [6].

Ultimately, Wikipedia provides a modern classification of viruses in terms of the genome, which is called the “Baltimore virus Classification,” although this is a modified version of it:

Picture 4. Classification of viruses according to V.I. Agol. Gray arrows — replication, pink — transcription, gray-black — reverse transcription of retro- and retroid viruses; pink font — intermediates (intermediates), black font in a frame — viral genomes; cDNA — single-stranded DNA. The scheme from the magazine “Nature”, № 9 (2009) [6].

Ultimately, Wikipedia provides a modern classification of viruses in terms of the genome, which is called the “Baltimore virus Classification,” although this is a modified version of it:

- viruses containing double-stranded DNA and not having an RNA stage;

- viruses containing double-stranded RNA;

- viruses containing a single-stranded DNA molecule;

- viruses containing a single-stranded RNA molecule of positive polarity;

- viruses containing a single-stranded RNA molecule of negative or double polarity;

- viruses containing a single-stranded RNA molecule and having in their life cycle a stage of DNA synthesis on an RNA matrix, retroviruses;

- viruses containing double-stranded DNA and having a stage of DNA synthesis on an RNA template in their life cycle are retroid viruses.

- spiral symmetry;

- cubic (icosahedral, quasi-spherical) symmetry;

- mixed type of symmetry;

- without a certain symmetry.

Picture 5. Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV). Leftward: VTM structure. There are 49 capsomers per three turns of the spiral (some are numbered). From the book “Medical Microbiology” by Ferdinando Dianzani, Thomas Albrecht and By Samuel Baron [7]. On the right: An electronic micrograph of the VTM virus. From the Nanometer website.

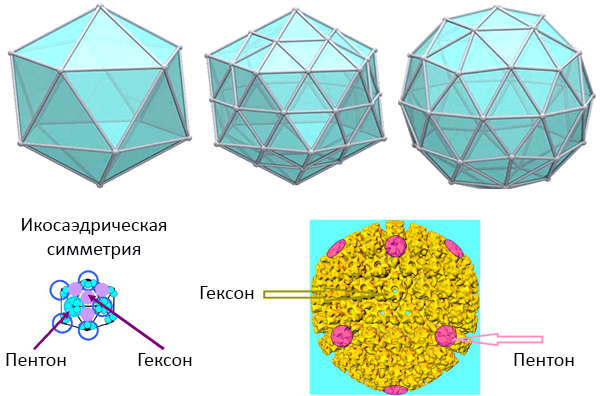

In viruses with icosahedral symmetry, the subunits are arranged in a regular icosahedron around DNA or RNA twisted into a ball. The simplest icosahedral capsid can be found, for example, in the satellite virus of tobacco necrosis [8]. (The word “satellite” means that the virus cannot build its capsid without the support of the tobacco necrosis virus, which ensures replication, which the CBNT does not carry out in the cell.) Each of its “facets” consists of three subunits.

Picture 5. Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV). Leftward: VTM structure. There are 49 capsomers per three turns of the spiral (some are numbered). From the book “Medical Microbiology” by Ferdinando Dianzani, Thomas Albrecht and By Samuel Baron [7]. On the right: An electronic micrograph of the VTM virus. From the Nanometer website.

In viruses with icosahedral symmetry, the subunits are arranged in a regular icosahedron around DNA or RNA twisted into a ball. The simplest icosahedral capsid can be found, for example, in the satellite virus of tobacco necrosis [8]. (The word “satellite” means that the virus cannot build its capsid without the support of the tobacco necrosis virus, which ensures replication, which the CBNT does not carry out in the cell.) Each of its “facets” consists of three subunits.

Picture 6. Icosahedral symmetry. From above: Icosahedral polyhedra. Bottom left: capsomers of the simplest icosahedral virus. Bottom right: the nucleocapsid of the herpes virus. Pictures: University of South Carolina (USA).

In addition to the simplest icosahedron, the capsid shape may be based on some complex icosahedron with 20T faces and 60T protomers, where T is the triangulation number (Fig. 6). To preserve the shape, the protein subunits (capsomers) of large icosahedral viruses are grouped into morphological (i.e., by external structure) groups, distinguishable using an electron microscope pentons at the vertices (5 subunits) and hexons at the faces (6 subunits) (Pic. 6).

The third type of symmetry can be attributed to the well-known T-even bacteriophage T4 (Fig. 7). Its head is an icosahedron with DNA (which is sometimes said to be “encapsulated” in the head), and the hollow tail inside has spiral symmetry (and can contract when interacting with the host cell – this is the main difference between even—numbered and odd-numbered phages). At the base there is a basal plate (with protrusions) and tail protein processes (fibrils). In the area of the so—called neck there is a collar of “tendrils” – fibrils necessary for attaching tail threads to them at rest. (Both the collar and the neck have hexagonal symmetry.)

Picture 6. Icosahedral symmetry. From above: Icosahedral polyhedra. Bottom left: capsomers of the simplest icosahedral virus. Bottom right: the nucleocapsid of the herpes virus. Pictures: University of South Carolina (USA).

In addition to the simplest icosahedron, the capsid shape may be based on some complex icosahedron with 20T faces and 60T protomers, where T is the triangulation number (Fig. 6). To preserve the shape, the protein subunits (capsomers) of large icosahedral viruses are grouped into morphological (i.e., by external structure) groups, distinguishable using an electron microscope pentons at the vertices (5 subunits) and hexons at the faces (6 subunits) (Pic. 6).

The third type of symmetry can be attributed to the well-known T-even bacteriophage T4 (Fig. 7). Its head is an icosahedron with DNA (which is sometimes said to be “encapsulated” in the head), and the hollow tail inside has spiral symmetry (and can contract when interacting with the host cell – this is the main difference between even—numbered and odd-numbered phages). At the base there is a basal plate (with protrusions) and tail protein processes (fibrils). In the area of the so—called neck there is a collar of “tendrils” – fibrils necessary for attaching tail threads to them at rest. (Both the collar and the neck have hexagonal symmetry.)

Picture 7. Electronic micrography of phage T4. Image: “Around the world“.

The smallpox vaccine virus (pic. 8) belongs to the latter type. The central part is called the core, it has the appearance of a biconcave lens and is surrounded by a smooth membrane. Its concavity is given by lateral (lateral) bodies containing a variety of enzymes for viral replication. The virion is surrounded by a lipoprotein membrane, which some scientists consider to be two closely spaced bilayer lipid membranes, while others consider to be a single membrane. In any case, virus-specific proteins and protein complexes are visible on the surface of this membrane.

Picture 7. Electronic micrography of phage T4. Image: “Around the world“.

The smallpox vaccine virus (pic. 8) belongs to the latter type. The central part is called the core, it has the appearance of a biconcave lens and is surrounded by a smooth membrane. Its concavity is given by lateral (lateral) bodies containing a variety of enzymes for viral replication. The virion is surrounded by a lipoprotein membrane, which some scientists consider to be two closely spaced bilayer lipid membranes, while others consider to be a single membrane. In any case, virus-specific proteins and protein complexes are visible on the surface of this membrane.

Pic 8. Smallpox vaccine virus. Leftward: an electronic photo of the virus. On the right: its structure. From the article “Creation of antiviral drugs against smallpox” by Stephen Harrison and co-authors [31].

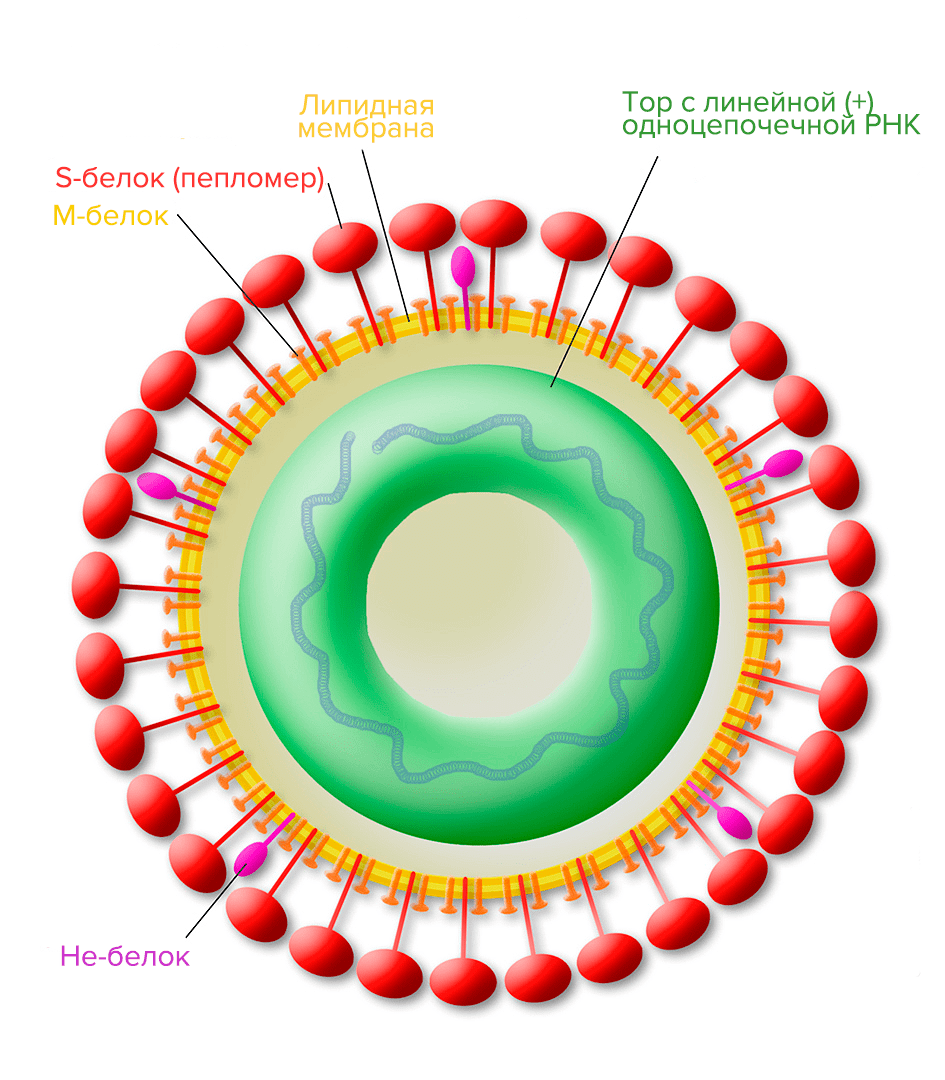

Complex (enveloped) viruses have an additional shell — the supercapsid, or peplos (as the outer part of the supercapsid is sometimes called), formed by a bilayer lipid membrane of cellular origin and specific viral proteins (more precisely, glycoproteins). Glycoprotein spikes — peplomeres (from the Greek. πεπλος — cape) — are morphological protein subunits of the supercapsid (Pic. 9).

Pic 8. Smallpox vaccine virus. Leftward: an electronic photo of the virus. On the right: its structure. From the article “Creation of antiviral drugs against smallpox” by Stephen Harrison and co-authors [31].

Complex (enveloped) viruses have an additional shell — the supercapsid, or peplos (as the outer part of the supercapsid is sometimes called), formed by a bilayer lipid membrane of cellular origin and specific viral proteins (more precisely, glycoproteins). Glycoprotein spikes — peplomeres (from the Greek. πεπλος — cape) — are morphological protein subunits of the supercapsid (Pic. 9).

Picture 9. Structure of the torovirus (it can cause gastroenteritis — inflammation of the stomach and intestines). M-protein is a membrane protein; S-protein is a glycoprotein spike; He—protein is a hemagglutininesterase protein complex involved in virus-cell fusion and suppression of immune responses.

The structure and diversity of viruses can be discussed for a long time, but it’s time to move on to the immediate topic of the review. However, finally, a little bit about one of the main mysteries of modern biology — the origin of viruses.

There are three main hypotheses (even groups of hypotheses) of the origin of viruses [9]:

Picture 9. Structure of the torovirus (it can cause gastroenteritis — inflammation of the stomach and intestines). M-protein is a membrane protein; S-protein is a glycoprotein spike; He—protein is a hemagglutininesterase protein complex involved in virus-cell fusion and suppression of immune responses.

The structure and diversity of viruses can be discussed for a long time, but it’s time to move on to the immediate topic of the review. However, finally, a little bit about one of the main mysteries of modern biology — the origin of viruses.

There are three main hypotheses (even groups of hypotheses) of the origin of viruses [9]:

- The “virus-first” hypothesis suggests that viruses have a precellular origin (precellular genetic elements), and later they evolved together with their host cells. But the fact that the virus cannot reproduce without a cell calls this theory into question.

- According to the “escape” hypothesis, viruses were part of the cellular machinery and separated from it — that is, these are “escaped” genes.

- The “reduction” hypothesis identifies viruses with RNA-containing cells that have turned to parasitism on their fellow cells, becoming peculiar endosymbionts (microorganisms living inside the host, benefiting it). Later, they lost their ability to translate independently, becoming RNA viruses. Moreover, this event occurred separately for each virus superfamily.

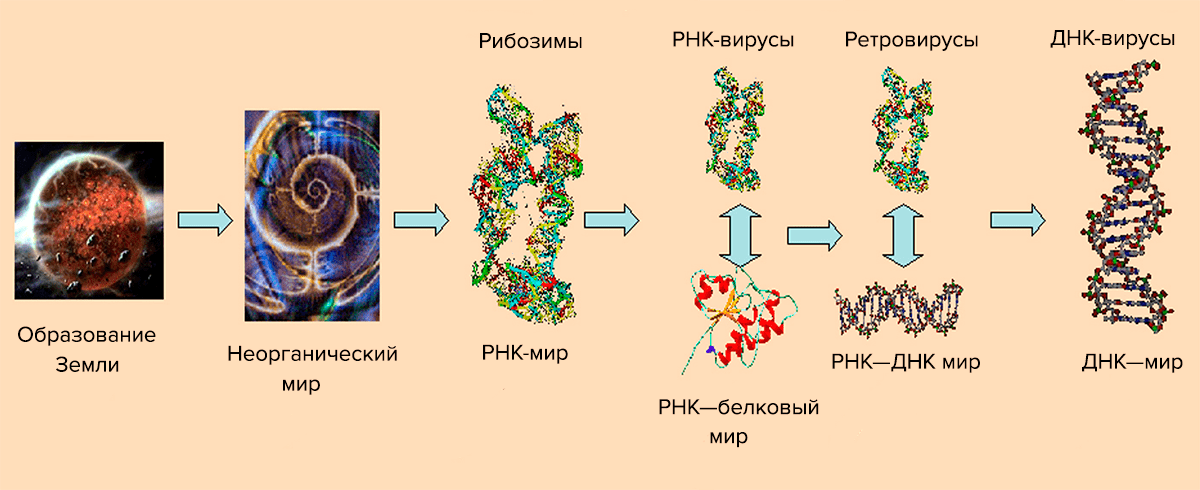

Picture 10. The scheme of virus evolution. From the article “Consequences of genetic variability and selection in viruses” by Niraiya Makadia from University of Saskatchewan [9].

Currently, the number of similar models and their combinations has increased. In its most general form, the structure of the evolutionary process of viruses is shown on pic. 10. She explains the appearance of viruses from the point of view of the theory of the “RNA world“, according to which the “division of labor” between DNA (storage of genetic information) and protein (primarily catalysis) occurred later than previously thought [10]. Initially, short self-replicating RNA molecules appeared, which acquired the ability to catalyze the synthesis of polypeptides. They are called ribozymes. RNA paired with a peptide has become a more efficient replication system, catalyzing each other. Then, complementary DNA appeared on the RNA matrix, taking over the current function. The RNA—protein stage corresponds to the appearance of RNA viruses that use their RNA genome to synthesize viral proteins. Later, the aforementioned reverse transcription process appeared, and with it retroviruses. According to this scheme, DNA viruses are the last stage. It should be noted that retroid viruses, apparently, appeared at the penultimate stage — the world of RNA and retro-DNA.

The information described above about the Viruses domain allows us to finally move on to the connection of these creatures with nanotechnology.

Picture 10. The scheme of virus evolution. From the article “Consequences of genetic variability and selection in viruses” by Niraiya Makadia from University of Saskatchewan [9].

Currently, the number of similar models and their combinations has increased. In its most general form, the structure of the evolutionary process of viruses is shown on pic. 10. She explains the appearance of viruses from the point of view of the theory of the “RNA world“, according to which the “division of labor” between DNA (storage of genetic information) and protein (primarily catalysis) occurred later than previously thought [10]. Initially, short self-replicating RNA molecules appeared, which acquired the ability to catalyze the synthesis of polypeptides. They are called ribozymes. RNA paired with a peptide has become a more efficient replication system, catalyzing each other. Then, complementary DNA appeared on the RNA matrix, taking over the current function. The RNA—protein stage corresponds to the appearance of RNA viruses that use their RNA genome to synthesize viral proteins. Later, the aforementioned reverse transcription process appeared, and with it retroviruses. According to this scheme, DNA viruses are the last stage. It should be noted that retroid viruses, apparently, appeared at the penultimate stage — the world of RNA and retro-DNA.

The information described above about the Viruses domain allows us to finally move on to the connection of these creatures with nanotechnology.

Self-deception virus, or in vivo nanotechnology

Self—assembly of viral particles is one of the first properties of a virus used by bionanotechnologists. Self—assembly, more precisely supramolecular self-assembly, is the spontaneous association of molecular “building blocks” through intermolecular non-covalent interactions (i.e. weak interactions not related to the direct overlap of the electron shells of atoms). This is a reversible phenomenon, which makes it possible to “choose” the most stable structure and correct packaging errors [11]. In biological systems, this takes on a particularly important meaning (Pic. 11). Picture 11. Modularity and convergence of biosampling. Modularity means that structural units can be combined into functionally active modules, and synthesis convergence implies the production of a final substance from units obtained separately through chains of successive chemical transformations. From an article by Scottish chemists Douglas Philip and J. Fraser Stoddart “Self-assembly in natural and artificial systems” [12].

Picture 11. Modularity and convergence of biosampling. Modularity means that structural units can be combined into functionally active modules, and synthesis convergence implies the production of a final substance from units obtained separately through chains of successive chemical transformations. From an article by Scottish chemists Douglas Philip and J. Fraser Stoddart “Self-assembly in natural and artificial systems” [12].

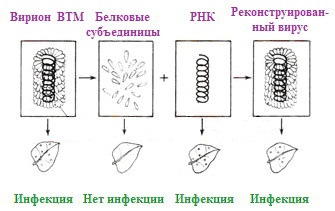

Picture 12. The experiment of Frenkel-Konrath and his colleagues, confirming the self-organization of TMV and the infectious ability of viral RNA (albeit less than that of the whole virus). From the website ePlantScience.com.

For the first time, virus self-organization was demonstrated in vitro (“in vitro”) using the example of VTM in 1955 by virologists Heinz Frenkel-Konrat and Robley Williams, who discovered the spontaneous assembly of virions from incubated purified viral proteins and RNA, and also described (after 2 years) the infectivity of viral RNA (Fig. 12). Later, work was carried out on the restoration of VTM and other spiral viruses from viral protein preparations and native NC has been conducted repeatedly.

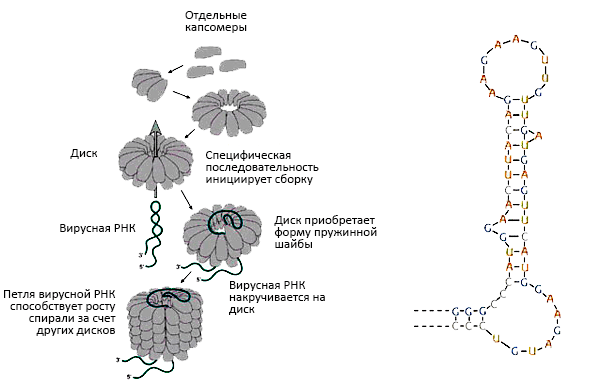

The final structure is formed spontaneously because it is thermodynamically advantageous, and the assembly process has a high equilibrium constant. In other words, self-assembly is a highly affinity process. The modules for assembly are disks of two protein layers (Pic. 13). When the RNA loop passes through the opening of the disk, it turns into two turns of a spiral, on which subsequent modules are “strung”. The advantage of such a modular assembly of identical “bricks” is the reduction of the genetic information required to encode this process, since there is no need to encode each disk separately. The weakness of the forces holding the entire structure contributes to the reversibility of self-assembly mentioned above.

Picture 12. The experiment of Frenkel-Konrath and his colleagues, confirming the self-organization of TMV and the infectious ability of viral RNA (albeit less than that of the whole virus). From the website ePlantScience.com.

For the first time, virus self-organization was demonstrated in vitro (“in vitro”) using the example of VTM in 1955 by virologists Heinz Frenkel-Konrat and Robley Williams, who discovered the spontaneous assembly of virions from incubated purified viral proteins and RNA, and also described (after 2 years) the infectivity of viral RNA (Fig. 12). Later, work was carried out on the restoration of VTM and other spiral viruses from viral protein preparations and native NC has been conducted repeatedly.

The final structure is formed spontaneously because it is thermodynamically advantageous, and the assembly process has a high equilibrium constant. In other words, self-assembly is a highly affinity process. The modules for assembly are disks of two protein layers (Pic. 13). When the RNA loop passes through the opening of the disk, it turns into two turns of a spiral, on which subsequent modules are “strung”. The advantage of such a modular assembly of identical “bricks” is the reduction of the genetic information required to encode this process, since there is no need to encode each disk separately. The weakness of the forces holding the entire structure contributes to the reversibility of self-assembly mentioned above.

Picture 13. Assembly of the spiral tobacco mosaic virus by the type of “traveling loop” of viral RNA. The loop penetrates between two layers of disks, wraps around one of its turns and continues to “travel” between the layers of the spiral, forcing the other disks to be completed in their place. An illustration from the book “General Virology” by molecular biologist, biochemist and virologist Edward K. Wagner [13].On the right: an RNA loop that initiates the assembly of virus nanoparticles. From the book by Nigel Dimmock and co-authors.

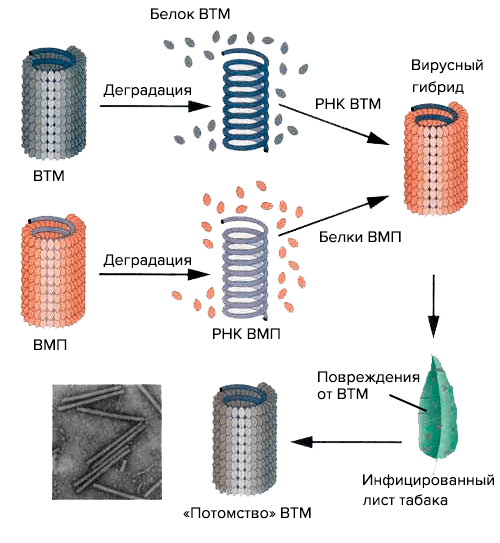

By the way, the aforementioned virologist Frankel-Konrath and his colleagues in the laboratory also conducted an experiment to create a viral hybrid consisting of tobacco mosaic virus RNA and a protein “coat” of psyllium mosaic virus (VMP) (Holmes psyllium virus). The researchers infected tobacco with the resulting virus, which caused characteristic damage to its leaves. They were characteristic of the donor RNA, i.e., for VTM, and the viruses extracted from them had the structure of VTM (Pic. 14). The moral of this experience is as follows: firstly, RNA determines the structure of the virus by encoding its proteins, and secondly, the tobacco mosaic virus is a promising object of genetically engineered bionanotechnology.

Picture 13. Assembly of the spiral tobacco mosaic virus by the type of “traveling loop” of viral RNA. The loop penetrates between two layers of disks, wraps around one of its turns and continues to “travel” between the layers of the spiral, forcing the other disks to be completed in their place. An illustration from the book “General Virology” by molecular biologist, biochemist and virologist Edward K. Wagner [13].On the right: an RNA loop that initiates the assembly of virus nanoparticles. From the book by Nigel Dimmock and co-authors.

By the way, the aforementioned virologist Frankel-Konrath and his colleagues in the laboratory also conducted an experiment to create a viral hybrid consisting of tobacco mosaic virus RNA and a protein “coat” of psyllium mosaic virus (VMP) (Holmes psyllium virus). The researchers infected tobacco with the resulting virus, which caused characteristic damage to its leaves. They were characteristic of the donor RNA, i.e., for VTM, and the viruses extracted from them had the structure of VTM (Pic. 14). The moral of this experience is as follows: firstly, RNA determines the structure of the virus by encoding its proteins, and secondly, the tobacco mosaic virus is a promising object of genetically engineered bionanotechnology.

Picture 14. The Frankel-Konrath and Singer experiment on the reconstruction of a hybrid virus from components of the VTM and VMP viruses. A diagram from the Bio-Siva website.

This classic experiment has been repeated many times, including by our virologists from the Department of Virology, Faculty of Biology, Moscow State University, led by Joseph Grigorievich Atabekov. For example, in 2011, Professor I.G. Atabekov’s group, together with the Scanning Probe Microscopy Group at Moscow State University, obtained viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs) based on the envelope protein of potato X virus (HVK) and heterologous (non-native) RNAs from: potexviruses (4 species), tobamovirus (VTM) and bromovirus (bonfire mosaic virus) [14].

Shell proteins can also repolymerize (self-assemble) without RNA to spiral virus-like particles (HPV) of any length. The influence of factors such as pH (acid-base balance) and ionic strength of the solution in which the building components of the virus are incubated should be taken into account (Pic. 15). Although the conditions of self-assembly are considered mild, one or another stage of this process depends on their variations [15].

Picture 14. The Frankel-Konrath and Singer experiment on the reconstruction of a hybrid virus from components of the VTM and VMP viruses. A diagram from the Bio-Siva website.

This classic experiment has been repeated many times, including by our virologists from the Department of Virology, Faculty of Biology, Moscow State University, led by Joseph Grigorievich Atabekov. For example, in 2011, Professor I.G. Atabekov’s group, together with the Scanning Probe Microscopy Group at Moscow State University, obtained viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs) based on the envelope protein of potato X virus (HVK) and heterologous (non-native) RNAs from: potexviruses (4 species), tobamovirus (VTM) and bromovirus (bonfire mosaic virus) [14].

Shell proteins can also repolymerize (self-assemble) without RNA to spiral virus-like particles (HPV) of any length. The influence of factors such as pH (acid-base balance) and ionic strength of the solution in which the building components of the virus are incubated should be taken into account (Pic. 15). Although the conditions of self-assembly are considered mild, one or another stage of this process depends on their variations [15].

Picture 15. The effect of pH and ionic strength on A-protein aggregation. A-protein are small polypeptide aggregates into which the shell breaks down from a weak alkali. From the book “Introduction to modern Virology” [15].

Picture 15. The effect of pH and ionic strength on A-protein aggregation. A-protein are small polypeptide aggregates into which the shell breaks down from a weak alkali. From the book “Introduction to modern Virology” [15].

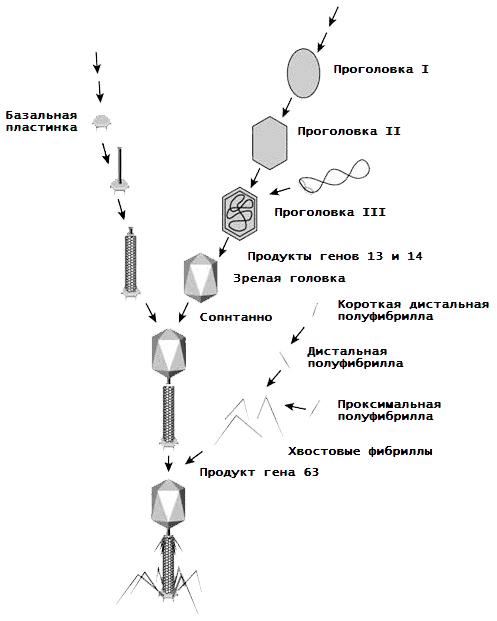

Picture 16. Assembly of bacteriophage T4.

It is worth mentioning the assembly of another type of virus, bacteriophages. Let’s look at it using the classic example of phage T4. As we already know, it has a mixed spiral-icosahedral symmetry, which boils down to the formation of protein subaggregates based on 54 types of proteins, and then a virion of them. What is the course of this process (Pic. 16) [16, 17]?

Picture 16. Assembly of bacteriophage T4.

It is worth mentioning the assembly of another type of virus, bacteriophages. Let’s look at it using the classic example of phage T4. As we already know, it has a mixed spiral-icosahedral symmetry, which boils down to the formation of protein subaggregates based on 54 types of proteins, and then a virion of them. What is the course of this process (Pic. 16) [16, 17]?

- The basal lamina (BP) is made up of 15 proteins, as well as several molecules of enzymes and folic acid.

- BP serves as a seed for assembling the tail of the virus, around which a spiral case is built (a product of gene 18).

- The head of the bacteriophage is preceded by a head (procapsid, a DNA-free precursor). It “grows” on the initiating protein complex (portal protein, connector) — a dodecamer of 12 subunits encoded by the 20 gene. This complex is attached to the inner surface of the cytoplasmic membrane of the host cell by means of a membrane scaffold protein, and a protein core grows on it, serving as “scaffolding” for procapsid II. Further, pentons and hexons from proteins gp24 and gp23 are grouped around this protein core. gene product), the core is destroyed, the gp24 and gp23 proteins are modified to gp24* and gp23*, the capsid increases and procapsid II detaches from the membrane along with the connector.

- Through the portal opening, the gp16 and gp17 proteins, with the participation of a connector and energy molecules of ATP, pack DNA into a procapsid. The DNA is cut off in the right place, and this “Pandora’s box” for bacteria is plugged with a plug from the products of genes 13 and 14.

- The head of the bacteriophage (more precisely gp23*) is “encrusted” with a network of HOC and SOC proteins.

- Each tail thread is connected from two halves — distal (removed from the virion and longer) and proximal (closer to the virion and shorter).

- The head and tail of the virus spontaneously connect.

- The tail and collar fibrils are fixed in place (and the tail fibrils are held by the collar fibrils as they should be).

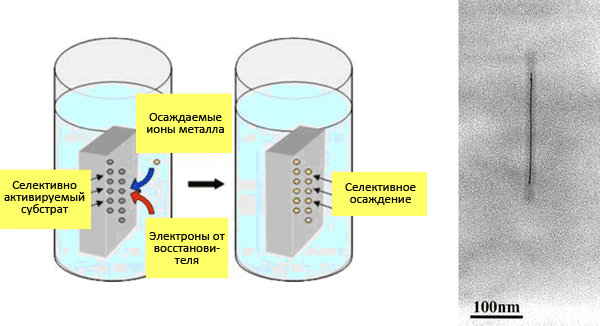

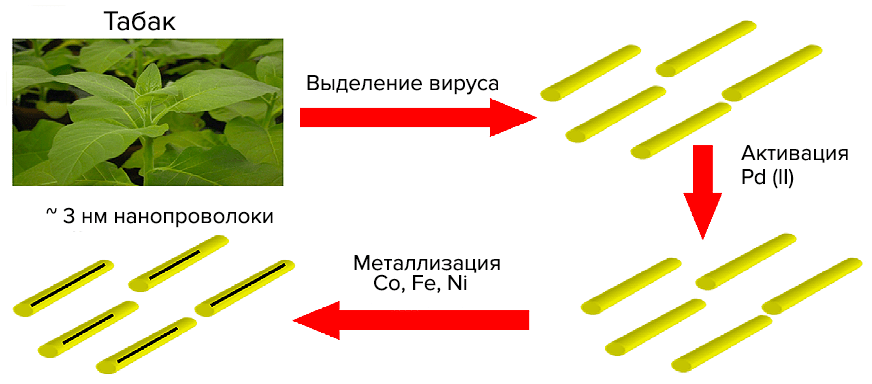

A godsend for Chubais

VTM nanoparticles are similar to inorganic nanostructures made of various compounds. This allows us to consider viruses as an object of inorganic materials science. Virions are used as matrices for the immobilization of metal nanoparticles (for example, gold) or metal-containing compounds on them [18]. One of the first in this direction is the work of nanotechnology chemist Mato Knez and colleagues from the Institute of Physics of Microstructures (Max Planck Society, Germany) on metallization of VTM nanoparticles to produce “3 nm nanowires” [19]. Such a synthesis, in which the template for the final material is a biostructure, is called biotemplate. The technology of metal deposition by chemical reduction is used in industry to create metal coatings with a thickness of micrometers. Non—conductive (current) surfaces are pre-activated – they are coated with a thin layer of metal (palladium Pd(II) or tin Sn(II)); then they are immersed in a precipitation bath containing metal ions and a reducing agent (which selflessly gives up electrons). Activated surfaces and a growing metal layer catalyze deposition. Here is a scheme of Pd activation (with palladium autocatalysis) of nickel (Ni(II)) deposition with palladium adsorption on the surface (Pd2+adsorption).: Virions were incubated with salts of tetrachloropalladium (PdCl42−) or tetrachloplatinic (PtCl42−) acid. The presence of dimethylamine borane guarantees the formation of Pd(II)- or Pt(II)-clusters. Next, virions (or rather protein aggregates) should be “bathed” in a bath of reducing agent (dimethylaminborane) and cobalt (nickel). The result is nanowires made of VTM virions with a diameter of ≈3 nm and a length of micrometers with a metallized axial channel. In Fig. 17 shows the essence of the method and a photograph of a cobalt VTM nanowire.

Virions were incubated with salts of tetrachloropalladium (PdCl42−) or tetrachloplatinic (PtCl42−) acid. The presence of dimethylamine borane guarantees the formation of Pd(II)- or Pt(II)-clusters. Next, virions (or rather protein aggregates) should be “bathed” in a bath of reducing agent (dimethylaminborane) and cobalt (nickel). The result is nanowires made of VTM virions with a diameter of ≈3 nm and a length of micrometers with a metallized axial channel. In Fig. 17 shows the essence of the method and a photograph of a cobalt VTM nanowire.

Picture 17. “Nanowire.” On the left: Electrochemical deposition scheme. From a presentation by Chinese physicist Zhigan Wu. On the right: electronic photography of nanowires with Co(II) (palladium activation). Under the protein “coat” is not RNA, but a wire 200 nm long and 3 nm in diameter. From the article by Mato Knez “Biotemplate synthesis of 3-nm nickel and cobalt nanowires” [19].

This year, in 2012, a similar article was published in which an “alloy” of cobalt or nickel with iron was introduced into the virus cavity [20]. The algorithm is the same, except that an aqueous solution with Co(II), Fe(II), and Ni(II) ions is used for metallization. Moreover, scientists knew that purification from phosphates allows ions to more selectively penetrate into the VTM channel. As a result, nickel is added to cobalt, iron and CoFe already in the bath, giving the necessary compounds (Pic. 18). It was found that nanowires with nickel have a high resistance to corrosion.

Picture 17. “Nanowire.” On the left: Electrochemical deposition scheme. From a presentation by Chinese physicist Zhigan Wu. On the right: electronic photography of nanowires with Co(II) (palladium activation). Under the protein “coat” is not RNA, but a wire 200 nm long and 3 nm in diameter. From the article by Mato Knez “Biotemplate synthesis of 3-nm nickel and cobalt nanowires” [19].

This year, in 2012, a similar article was published in which an “alloy” of cobalt or nickel with iron was introduced into the virus cavity [20]. The algorithm is the same, except that an aqueous solution with Co(II), Fe(II), and Ni(II) ions is used for metallization. Moreover, scientists knew that purification from phosphates allows ions to more selectively penetrate into the VTM channel. As a result, nickel is added to cobalt, iron and CoFe already in the bath, giving the necessary compounds (Pic. 18). It was found that nanowires with nickel have a high resistance to corrosion.

Picture 18. Synthesis of nanowires with a mixed “core”. From the article by Sinan Balsi and co-authors “Electrochemical synthesis of 3-nm doped nanowires based on tobacco mosaic virus” [20].

I think no one doubts that it is possible to metallize (or even “magnetize”) the virus from the outside. To prove this, it is worth mentioning the work of German nanotechnologists (including Mato Kneza) [21]. In it, scientists present a whole series of experiments on the metallization of the outer walls and the inner channel of the VTM:

Picture 18. Synthesis of nanowires with a mixed “core”. From the article by Sinan Balsi and co-authors “Electrochemical synthesis of 3-nm doped nanowires based on tobacco mosaic virus” [20].

I think no one doubts that it is possible to metallize (or even “magnetize”) the virus from the outside. To prove this, it is worth mentioning the work of German nanotechnologists (including Mato Kneza) [21]. In it, scientists present a whole series of experiments on the metallization of the outer walls and the inner channel of the VTM:

- binding of VTM uranyl ions (UO22+) and ruthenium ions (Ru(III)) for visualization of nanoparticles by electron microscopy;

- decoration of the outer surface with palladium clusters and

- electrochemical deposition of cobalt, nickel and gold on the inner and outer surfaces.

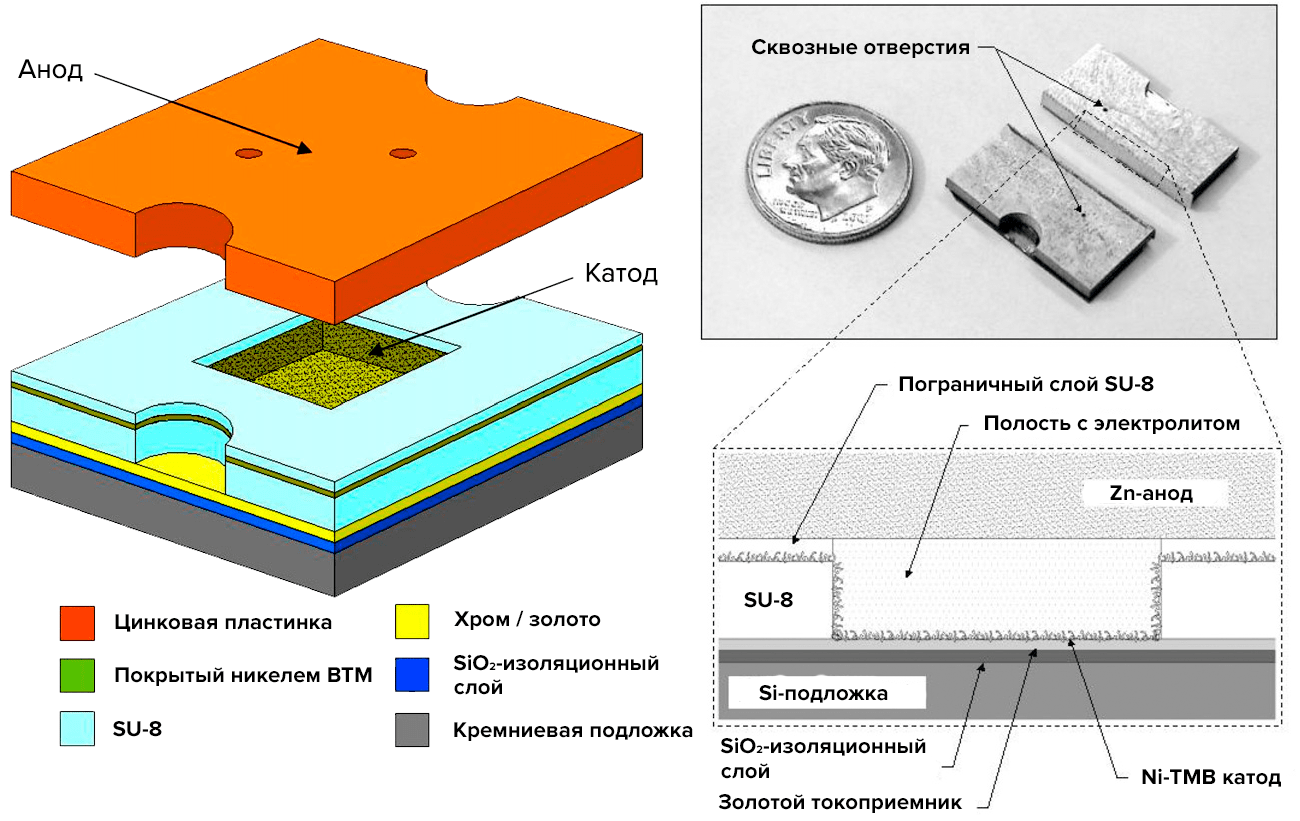

Picture 19. Microbattery. Leftward: a diagram of the layers of the microbattery. On the right: battery section. From the article “Nickel nanoelectrodes based on tobacco mosaic virus for microbatteries” by Konstantinos Gerasopoulos and his colleagues from University of Maryland [22].

Picture 19. Microbattery. Leftward: a diagram of the layers of the microbattery. On the right: battery section. From the article “Nickel nanoelectrodes based on tobacco mosaic virus for microbatteries” by Konstantinos Gerasopoulos and his colleagues from University of Maryland [22].

Picture 20. Assembly of nanoelectrodes based on VTM. From above: The course of modification of VTM. 1 — VTM is collected from a solution on a gold surface, 2 — the surface of virions is activated by a palladium catalyst, and 3 — nickel precipitation. Below: electron micrography of the obtained electrodes at high magnification. From the article by Konstantinos Gerasopoulos and co-authors [22].

Picture 20. Assembly of nanoelectrodes based on VTM. From above: The course of modification of VTM. 1 — VTM is collected from a solution on a gold surface, 2 — the surface of virions is activated by a palladium catalyst, and 3 — nickel precipitation. Below: electron micrography of the obtained electrodes at high magnification. From the article by Konstantinos Gerasopoulos and co-authors [22].

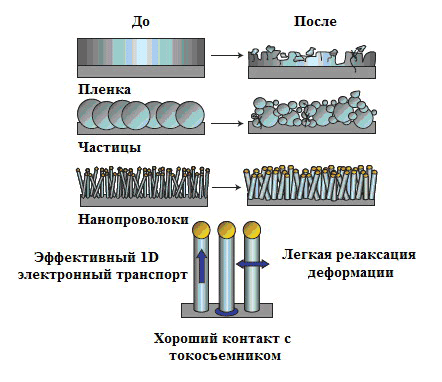

Picture 21. Morphological changes of silicon after an electrochemical cycle. Nanowires grown on a current collector do not disintegrate or collapse. Strain relaxation (the deformation that remains after the removal of the deforming force, but slowly disappears over time) proceeds easily, allowing the wires to only increase in size when the battery is running. Electronic transport using such 1D structures is very efficient. From Yi Kyu’s article “Highly efficient anodes for lithium batteries based on silicon nanowires” [24].

First, dielectric silicon dioxide SiO2 is deposited at reduced pressure to shield the cathode from the silicon substrate (“wafers”). Chromium and gold cover the dielectric during evaporation under the action of an electron beam (electron beam evaporation). Chrome is the adhesive layer, which glues the layers together, and gold is the pantograph and the base for assembling the VTM. After SU-8 lithography, the silicon substrate is attached to the cathode, and the assembly of the VTM electrodes on gold begins (Pic. 20). The tobacco virus was chosen not as a simple one, but as a genetically engineered one, with a cysteine residue (cis—SH) on each subunit — VTM-1-cis. Finally, the cathode and anode are attached to the photoresist with the same orientation.

But what advantages can a tobacco virus have in the case of a battery? The authors compared batteries with and without viral nanoparticles and showed that the capacity of bionobatteries is six times higher than that of “conventional” nanobatteries. And as the distance between the electrodes decreases, the capacitance increases even more. The simplicity of viral self-organization and the metallization process confirm the possibility of producing more compact energy storage devices.

Scientists from Maryland have also found an application for tobacco mosaic virus for anodes, but already lithium-ion batteries (LIAS), which have caused a real boom in modern energy and electronics [23]. But, like the aforementioned microbatteries, they need to increase their capacity with small sizes. Already in 2007, a group of Chinese materials scientist and nanotechnology researcher Yi Kyu in At Stanford University, she invented the so—called nanowire batteries with silicon anodes [24]. Such an anode is a stainless steel plate (current collector) coated with nanowires of the composition VTM—1-cis/Ni/Si. It would seem, why not just cover the anode with silicon? The problem is the volumetric deformation of such continuous coatings, which swell after a charge-discharge cycle, during which lithium ions pass from one electrode to another and vice versa (Pic. 21).

Maryland scientists have found a way to make silicon nanowires even more efficient and less frayed than Yi Kyu’s. According to their method, the anode can be obtained in four steps.:

Picture 21. Morphological changes of silicon after an electrochemical cycle. Nanowires grown on a current collector do not disintegrate or collapse. Strain relaxation (the deformation that remains after the removal of the deforming force, but slowly disappears over time) proceeds easily, allowing the wires to only increase in size when the battery is running. Electronic transport using such 1D structures is very efficient. From Yi Kyu’s article “Highly efficient anodes for lithium batteries based on silicon nanowires” [24].

First, dielectric silicon dioxide SiO2 is deposited at reduced pressure to shield the cathode from the silicon substrate (“wafers”). Chromium and gold cover the dielectric during evaporation under the action of an electron beam (electron beam evaporation). Chrome is the adhesive layer, which glues the layers together, and gold is the pantograph and the base for assembling the VTM. After SU-8 lithography, the silicon substrate is attached to the cathode, and the assembly of the VTM electrodes on gold begins (Pic. 20). The tobacco virus was chosen not as a simple one, but as a genetically engineered one, with a cysteine residue (cis—SH) on each subunit — VTM-1-cis. Finally, the cathode and anode are attached to the photoresist with the same orientation.

But what advantages can a tobacco virus have in the case of a battery? The authors compared batteries with and without viral nanoparticles and showed that the capacity of bionobatteries is six times higher than that of “conventional” nanobatteries. And as the distance between the electrodes decreases, the capacitance increases even more. The simplicity of viral self-organization and the metallization process confirm the possibility of producing more compact energy storage devices.

Scientists from Maryland have also found an application for tobacco mosaic virus for anodes, but already lithium-ion batteries (LIAS), which have caused a real boom in modern energy and electronics [23]. But, like the aforementioned microbatteries, they need to increase their capacity with small sizes. Already in 2007, a group of Chinese materials scientist and nanotechnology researcher Yi Kyu in At Stanford University, she invented the so—called nanowire batteries with silicon anodes [24]. Such an anode is a stainless steel plate (current collector) coated with nanowires of the composition VTM—1-cis/Ni/Si. It would seem, why not just cover the anode with silicon? The problem is the volumetric deformation of such continuous coatings, which swell after a charge-discharge cycle, during which lithium ions pass from one electrode to another and vice versa (Pic. 21).

Maryland scientists have found a way to make silicon nanowires even more efficient and less frayed than Yi Kyu’s. According to their method, the anode can be obtained in four steps.:

- Self-assembly of VTM-1-cis and simultaneous immersion of stainless steel discs in a solution with a virus to attach virions to them.

- Activation of VTM-1-cis by catalytic palladium clusters by reducing Pd2+ to Pd0 using hypophosphite.

- Electrochemical deposition of nickel on the surface of virus particles in a NiCl2 bath and dimethylamine borane reducing agent.

- After evaporation of moisture in a vacuum furnace, silicon is sprayed by condensation from steam.

Picture 22. Nanowires based on VTM-1-cis/Ni/Si. Leftward: the structure of a single wire. In the centre: VTM-1-cis/Ni/Si nanowires after silicon deposition. On the right: they are the same after 75 cycles of charging/discharging the battery. From the article by Maryland scientists “Virus-containing silicon anodes for lithium-ion batteries” [23].

Based on the electron micrographs (Pic. 22), it can be argued that such three-layer wires are organized on steel discs mainly vertically. After 75 cycles, the thickness of the silicon layer (with lithium deposited on it) increased by 112 nm — comparatively not much (including due to strain relaxation). The new LIAS demonstrate high capacitance (almost a 10-fold increase compared to graphite electrodes), excellent stability to overcharging (low capacity drop) and high wear resistance.

Such technologies speak loudly about the emergence of a new strategy in the development of inexpensive and versatile synthetic technologies for the storage of electrical energy.

As a postscript: Returning to the basic nanotechnology concepts, we can confidently say that the template synthesis that we have encountered is an example of a bottom-up liquid-phase method that allows us to assemble multi-tiered (or multilayer) structures from the initial blocks (Pic. 23).

Picture 22. Nanowires based on VTM-1-cis/Ni/Si. Leftward: the structure of a single wire. In the centre: VTM-1-cis/Ni/Si nanowires after silicon deposition. On the right: they are the same after 75 cycles of charging/discharging the battery. From the article by Maryland scientists “Virus-containing silicon anodes for lithium-ion batteries” [23].

Based on the electron micrographs (Pic. 22), it can be argued that such three-layer wires are organized on steel discs mainly vertically. After 75 cycles, the thickness of the silicon layer (with lithium deposited on it) increased by 112 nm — comparatively not much (including due to strain relaxation). The new LIAS demonstrate high capacitance (almost a 10-fold increase compared to graphite electrodes), excellent stability to overcharging (low capacity drop) and high wear resistance.

Such technologies speak loudly about the emergence of a new strategy in the development of inexpensive and versatile synthetic technologies for the storage of electrical energy.

As a postscript: Returning to the basic nanotechnology concepts, we can confidently say that the template synthesis that we have encountered is an example of a bottom-up liquid-phase method that allows us to assemble multi-tiered (or multilayer) structures from the initial blocks (Pic. 23).

Picture 23. Template assembly

Picture 23. Template assembly

Smoking is harmful to your health!.. And the tobacco virus can protect him.

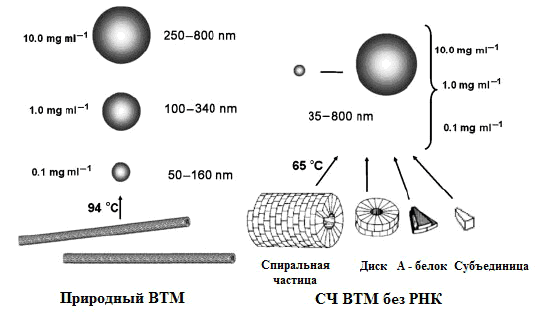

As is probably already clear, the tobacco mosaic virus harms tobacco (in fact, it infects representatives of nine plant families). However, people have found numerous uses for it. And not only in technology (this was discussed in the previous section), but also in medicine. This is a truly magical nanovaccine developed by Professor I.G. Atabekov’s group at the Department of Virology at Moscow State University. A vaccine is a means to create or improve immunity (the so—called acquired active immunity). In this case, the vaccine is created on the basis of antigens (foreign molecules that the immune system reacts to). The essence of the method is to create a carrier (platform) for antigen/epitopes (sections of protein antigens capable of binding to an antibody), which uses spherical viral particles of TMV and other spiral phytoviruses (and their fragments).Viral spherical nanoparticles

The aforementioned nanoplatforms for antigens can be obtained by thermal denaturation of the virus envelope protein (for example, VTM). In 1956, virologist Roger Hart showed that heat treatment of TM particles at a temperature of 80-98 °C for 10 seconds leads to swelling of virions due to protein denaturation and their transformation into spherical particles [25]. Russian virologists have found out that the size of spherical particles varies in the range of 50-800+ nm. To obtain spherical nanoparticles (SNPs), they used the tobacco mosaic virus itself and its protein envelope [26]. Electron microscopy revealed two stages of thermal transformation of the native virus (Pic. 24):- Heating to 90 °C is the swelling of particles from one or both ends and the formation of non—spherical particles of various sizes and shapes.

- Further heating to 94 °C is a mature HF.

Picture 24. Two-stage modification of the VTM in the LF. Leftward: The first stage, the temperature is 90 °C. On the right: further heating, temperature 94 °C. Photos from the article “Temperature modification of native tobacco mosaic virus and VTM proteins without RNA into spherical nanoparticles” by I.G. Atabekov and his colleagues [26].

Heating rod-shaped VTMS at 94-98 °C gives a 100% yield of HF, the volume of which does not necessarily correspond to the volume of VTM “sticks” (radius about 52 nm). All SNPs are insoluble in water and can exist as a colloidal solution or a stable suspension. Interestingly, SNPs are obtained from any fragments of the VTM shell, up to A-proteins (but at lower temperatures due to lower stability than a complete VTM) (Pic. 25).

Picture 24. Two-stage modification of the VTM in the LF. Leftward: The first stage, the temperature is 90 °C. On the right: further heating, temperature 94 °C. Photos from the article “Temperature modification of native tobacco mosaic virus and VTM proteins without RNA into spherical nanoparticles” by I.G. Atabekov and his colleagues [26].

Heating rod-shaped VTMS at 94-98 °C gives a 100% yield of HF, the volume of which does not necessarily correspond to the volume of VTM “sticks” (radius about 52 nm). All SNPs are insoluble in water and can exist as a colloidal solution or a stable suspension. Interestingly, SNPs are obtained from any fragments of the VTM shell, up to A-proteins (but at lower temperatures due to lower stability than a complete VTM) (Pic. 25).

Picture 25. A scheme for the synthesis of SNPs from native VTM (left) and protein aggregates of VTM (right). The concentrations of the initial structures and the sizes of the HF are indicated. From the same article by I.G. Atabekov [26].

The advantage of using VTM without RNA is that when heated, they do not turn into non-spherical particles, as well as the independence of the size of the LF from the protein concentration. Thus, the conversion of the shell protein to LF is a one—step process. The main advantages of this type of carrier for the antigen are:

Picture 25. A scheme for the synthesis of SNPs from native VTM (left) and protein aggregates of VTM (right). The concentrations of the initial structures and the sizes of the HF are indicated. From the same article by I.G. Atabekov [26].

The advantage of using VTM without RNA is that when heated, they do not turn into non-spherical particles, as well as the independence of the size of the LF from the protein concentration. Thus, the conversion of the shell protein to LF is a one—step process. The main advantages of this type of carrier for the antigen are:

- These SNPs are safe for humans and other animals, as they are obtained from plant viruses and at high temperatures (sterilized preparations), as well as due to the absence of RNA.

- The genetic variability of antigens immobilized on the surface of the HF due to the genetic inertia of the particles is excluded.

- Phytoviruses from the genera tobamovirus, potexvirus and gordeivirus can be easily isolated from infected leaves.

- A wide variety of proteins (including those with high biological and immunogenic activity) quickly adsorb on their surface.

- The ability to quickly obtain particles of the required size.

- High resistance to freezing (up to -20 °C), reheating (up to 98 °C) and storage for more than 6 months (at 4 °C).

- The formation of ensembles with peptides and peptide complexes does not require a genetic change in the structure of protein subunits.

Vaccine

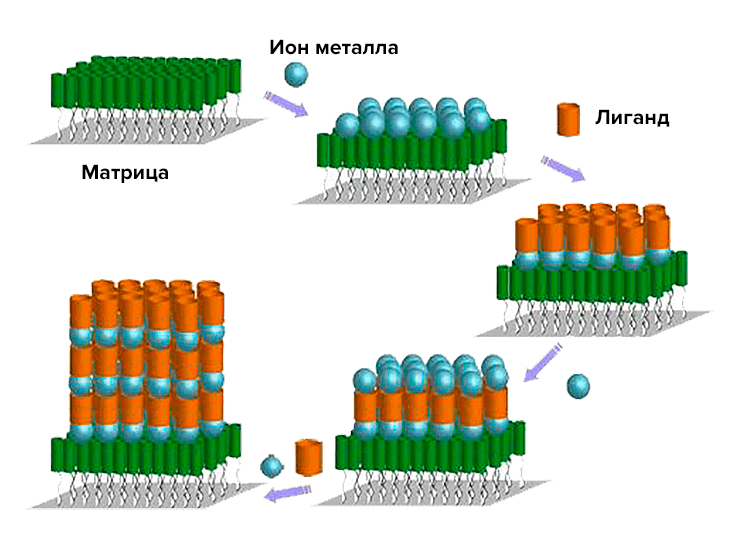

Now we should move on to the vaccine itself. Atabekov’s work investigated a variety of immunogenic (capable of producing antibodies) ensembles based on viral SNF carriers and antigens (or epitopes). Other viral agents capable of presenting antigens (i.e., presenting the antigen to T lymphocytes that destroy foreign proteins), affinity-conjugated antigenic systems (ACAS), have already been found. They are viruses whose shell protein is genetically or chemically modified and has binding sites for various foreign structures of a protein nature. Picture 26. Fluorescently labeled SNF–ZFB complexes. SNF obtained from native VTM virions were incubated with ZFB in water at room temperature. The complexes are stabilized with 0.05% formaldehyde solution. From the same article by I.G. Atabekov [26].

For example, in the USA in 2010, ACAS based on the papaya mosaic virus and from virus—like particles based on its shell containing affinity components (AK) – molecules or compounds capable of specifically binding to the desired antigens and protein of the virus shell [25]. Antibodies and their fragments, streptavidin protein (combines with biotin, labeled antigen), natural ligands and their binding domains, peptides and their parts can be attributed to AK. Conjugated antigens can, if necessary, attach antigens to themselves. The viral protein, in turn, needs modification; for example, it is possible to genetically remove amino acids at the N- or/and C-ends of the protein chain or/and replace some amino acids. But at ACAS has a number of disadvantages, in particular, low bioactivity, complex preparation procedure, genetic instability, strict specificity of components and low sorption capacity for antigens.

The connection of SNF with proteins began to be investigated by obtaining complexes of SNF—fluorescent protein. In particular, virologists combined green fluorescent protein (FFB) with LF (Pic. 26) [26].

It was also possible to attach potato X virus envelope proteins fluorescently labeled with fluoresceinisothiocyanate (FITC) to the SNF. At the same time, nothing special was done: simple incubation of the SNF and the target protein, followed by stabilization with formaldehyde; interactions between the SNF and the antigen/epitope before covalent stabilization can be attributed to electrostatic and/or hydrophobic. Eventually, the researchers came up with even more sophisticated “sandwich” structures: SNF and ZFB (antigen) à primary antibodies (mouse) à secondary anti-mouse antibodies (chicken) with Alexa fluorophore (green) or SNF à a mixed product of N-deleted CVC envelope protein and antigenic determinant (=epitope) of plum pox virus (VOS) à primary rabbit antibodies against plum pox virus à secondary anti-rabbit antibodies with Alexa fluorophore (red) (pic. 27) [28].

Picture 26. Fluorescently labeled SNF–ZFB complexes. SNF obtained from native VTM virions were incubated with ZFB in water at room temperature. The complexes are stabilized with 0.05% formaldehyde solution. From the same article by I.G. Atabekov [26].

For example, in the USA in 2010, ACAS based on the papaya mosaic virus and from virus—like particles based on its shell containing affinity components (AK) – molecules or compounds capable of specifically binding to the desired antigens and protein of the virus shell [25]. Antibodies and their fragments, streptavidin protein (combines with biotin, labeled antigen), natural ligands and their binding domains, peptides and their parts can be attributed to AK. Conjugated antigens can, if necessary, attach antigens to themselves. The viral protein, in turn, needs modification; for example, it is possible to genetically remove amino acids at the N- or/and C-ends of the protein chain or/and replace some amino acids. But at ACAS has a number of disadvantages, in particular, low bioactivity, complex preparation procedure, genetic instability, strict specificity of components and low sorption capacity for antigens.

The connection of SNF with proteins began to be investigated by obtaining complexes of SNF—fluorescent protein. In particular, virologists combined green fluorescent protein (FFB) with LF (Pic. 26) [26].

It was also possible to attach potato X virus envelope proteins fluorescently labeled with fluoresceinisothiocyanate (FITC) to the SNF. At the same time, nothing special was done: simple incubation of the SNF and the target protein, followed by stabilization with formaldehyde; interactions between the SNF and the antigen/epitope before covalent stabilization can be attributed to electrostatic and/or hydrophobic. Eventually, the researchers came up with even more sophisticated “sandwich” structures: SNF and ZFB (antigen) à primary antibodies (mouse) à secondary anti-mouse antibodies (chicken) with Alexa fluorophore (green) or SNF à a mixed product of N-deleted CVC envelope protein and antigenic determinant (=epitope) of plum pox virus (VOS) à primary rabbit antibodies against plum pox virus à secondary anti-rabbit antibodies with Alexa fluorophore (red) (pic. 27) [28].

Picture 27. Fluorescent complexes of SNF with antibodies

Picture 27. Fluorescent complexes of SNF with antibodies

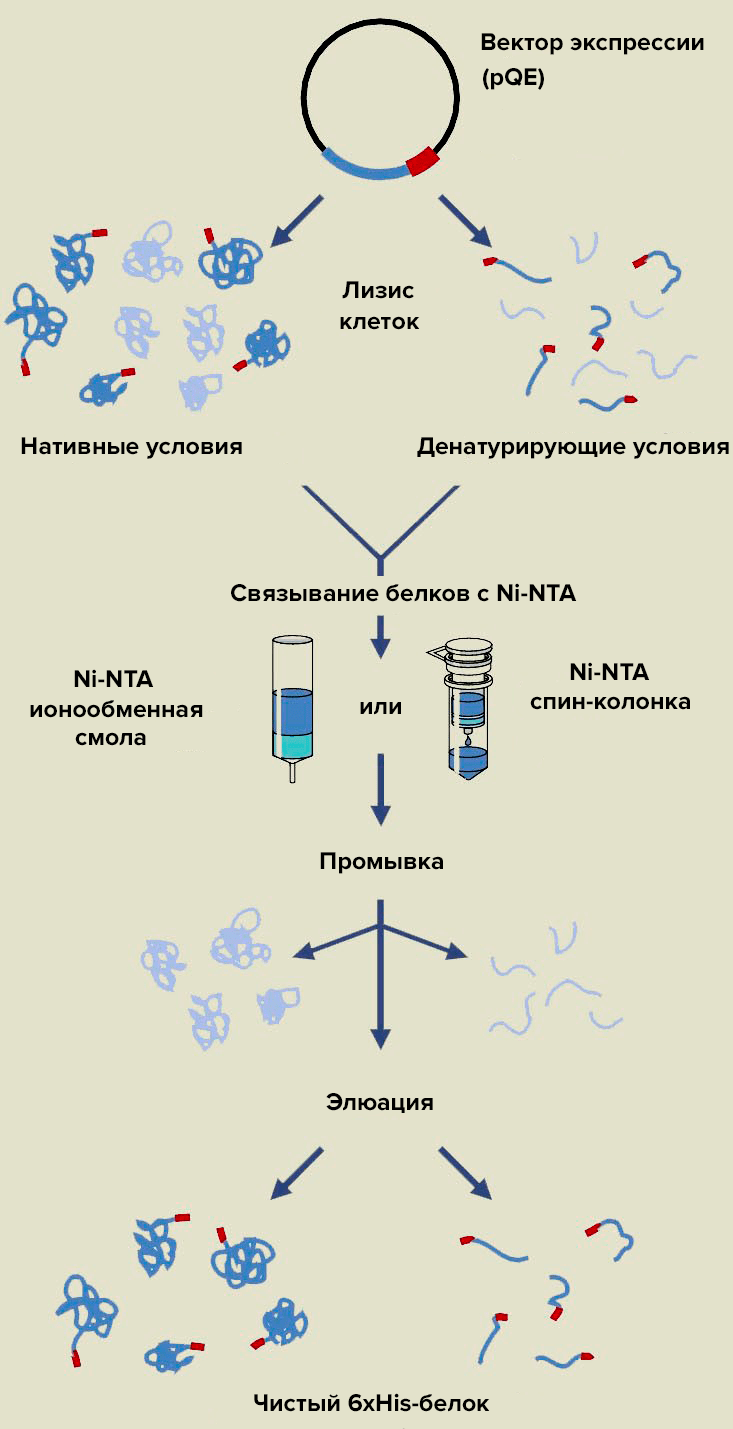

Picture 28. Affinity chromatography of recombinant proteins on Ni-HT agarose sorbent.Atabekov’s group uses denaturing conditions (because the protein is insoluble) and Ni-HTA in the form of a chromatographic resin (spin column is a polypropylene tube with adsorbent for purification of biomolecules by centrifugation). Washing involves the separation of impurity components that are not fixed on the adsorbent, and affinity elution is the removal of proteins from the column due to molecular recognition.

Picture 28. Affinity chromatography of recombinant proteins on Ni-HT agarose sorbent.Atabekov’s group uses denaturing conditions (because the protein is insoluble) and Ni-HTA in the form of a chromatographic resin (spin column is a polypropylene tube with adsorbent for purification of biomolecules by centrifugation). Washing involves the separation of impurity components that are not fixed on the adsorbent, and affinity elution is the removal of proteins from the column due to molecular recognition.

Picture 29. Electron micrography of nanoparticles of SNF → hemagglutinin H5 polyepitope of human influenza A virus → primary antibodies → secondary antibodies → fluorophore. From the article by I.G. Atabekov “Immunogenic compositions from spherical platforms and foreign antigens based on VTM” [28].

But all of the above antigens are either plant—based (HVK, VOS) or from jellyfish (ZFB), but not human. Our scientists have solved this problem by associating a number of antigens harmful to humans with HPV: polyepitope A of rubella virus (tandem antigenic determinants of glycoprotein E1), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) with M2e epitope of human influenza A virus, tetraepitope hemagglutinin (4 monoepitopes) H5 of human influenza A virus [28]. The mentioned complexes (as well as the complex containing CVC and the VOC epitope) contained His6-tag to facilitate chromatographic purification of recombinant proteins (Pic. 28) [28].

In all cases, the resulting vaccine “beads” look almost the same on electron micrographs of preparations obtained by immunofluorescence or immunosiltered (instead of a fluorophore, a colloidal gold nanoparticle) labeling. In Fig. 29 shows a photo of a nanovaccine of LCH, a polyepitope of hemagglutinin H5 of the human influenza A virus [28].

The immunogenicity of the antigens in combination with the SNF was confirmed by a series of experiments on mice. For example, comparing the activity of formaldehyde—stabilized SNF-protein shell complexes of CVC (or mixtures of these components) and CVC alone, it was found that the antiserum titer (a quantitative parameter characterizing the interaction of antibodies with antigen) in the first case is 10 times higher. This indicates that SNPs have an immunostimulating activity that increases the humoral immune response, which produces antibodies according to the “one antigen — one antibody” principle. If in this case the difference between the LCH—antigen complex and their mixture in activity is small, then for a vaccine containing VOC and CVC, this difference is very significant. Thus, the immunogenicity of the vaccine is influenced by the antigen itself [28].

To summarize, we can safely state the beginning of a new round in the development of modern medicine, associated with the emergence of a unique, biologically stable, safe nanovaccine based on plant viruses. We can only wait for the stage of clinical trials to replace laboratory research as soon as possible, giving rise to the widespread use of this miracle of nanobiotechnology.

Picture 29. Electron micrography of nanoparticles of SNF → hemagglutinin H5 polyepitope of human influenza A virus → primary antibodies → secondary antibodies → fluorophore. From the article by I.G. Atabekov “Immunogenic compositions from spherical platforms and foreign antigens based on VTM” [28].

But all of the above antigens are either plant—based (HVK, VOS) or from jellyfish (ZFB), but not human. Our scientists have solved this problem by associating a number of antigens harmful to humans with HPV: polyepitope A of rubella virus (tandem antigenic determinants of glycoprotein E1), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) with M2e epitope of human influenza A virus, tetraepitope hemagglutinin (4 monoepitopes) H5 of human influenza A virus [28]. The mentioned complexes (as well as the complex containing CVC and the VOC epitope) contained His6-tag to facilitate chromatographic purification of recombinant proteins (Pic. 28) [28].

In all cases, the resulting vaccine “beads” look almost the same on electron micrographs of preparations obtained by immunofluorescence or immunosiltered (instead of a fluorophore, a colloidal gold nanoparticle) labeling. In Fig. 29 shows a photo of a nanovaccine of LCH, a polyepitope of hemagglutinin H5 of the human influenza A virus [28].

The immunogenicity of the antigens in combination with the SNF was confirmed by a series of experiments on mice. For example, comparing the activity of formaldehyde—stabilized SNF-protein shell complexes of CVC (or mixtures of these components) and CVC alone, it was found that the antiserum titer (a quantitative parameter characterizing the interaction of antibodies with antigen) in the first case is 10 times higher. This indicates that SNPs have an immunostimulating activity that increases the humoral immune response, which produces antibodies according to the “one antigen — one antibody” principle. If in this case the difference between the LCH—antigen complex and their mixture in activity is small, then for a vaccine containing VOC and CVC, this difference is very significant. Thus, the immunogenicity of the vaccine is influenced by the antigen itself [28].

To summarize, we can safely state the beginning of a new round in the development of modern medicine, associated with the emergence of a unique, biologically stable, safe nanovaccine based on plant viruses. We can only wait for the stage of clinical trials to replace laboratory research as soon as possible, giving rise to the widespread use of this miracle of nanobiotechnology.

The Joy of a tycoon

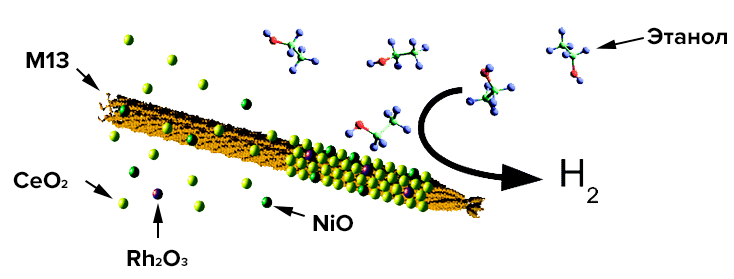

Over the past 10 years, the possibility of producing hydrogen from ethanol for use in fuel cells promises a real improvement in the operation of vehicles and autonomous energy generators. Materials scientists from The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has developed a nanocrystalline catalyst that allows the reforming of ethanol with good hydrogen yields (Pic. 31) [29]. Currently, the method of catalytic oxidative steam conversion of water-ethanol mixtures is used in the hydrogen energy industry, in particular using a Rh@CeO2 rhodium-cerium catalyst at a temperature of 650 °C. In fact, this process is described by the reaction C2H5OH + 2H2O + 1/2O2 → 2CO2 + 5H2, proceeding with a small release of heat (weakly exothermic reaction). Catalysts should activate both ethanol and water molecules to completely oxidize all carbon fragments, and should not have strong acidity and hydrogenating activity (the ability to attach hydrogen to reagents) in order to prevent the formation of ethylene (C2H4) and methane (CH4). Metallonized catalysts based on cerium dioxide are excellent because they are able to detach oxygen from water at relatively low temperatures. By combining the rhodium of the catalyst with Rh—Ni@CeO2 nickel, it is possible to increase the “operability” of the catalyst during reforming, especially at low temperatures. “Operability” should be understood as the efficiency of the breakdown of ethanol into smaller molecules by breaking the carbon—carbon bond. Bacteriophage M13 is a filamentous virus (Fig. 30), from which self-organizing nanowires can be obtained by bioengineering modification of surface proteins to attach the required materials to them. The purpose of this study is to show the possibility of obtaining a catalyst from M13 with excellent dispersion, high thermal stability, and good surface porosity. Picture 30. The bacteriophage M13 binds cerium, nickel and rhodium, creating a nanocrystalline catalyst for reforming ethanol into hydrogen. From the article by bioengineer and materials scientist Angela Belcher “Hydrogen production using a nanocrystalline protein template catalyst based on the bacteriophage M13” [29].

Picture 30. The bacteriophage M13 binds cerium, nickel and rhodium, creating a nanocrystalline catalyst for reforming ethanol into hydrogen. From the article by bioengineer and materials scientist Angela Belcher “Hydrogen production using a nanocrystalline protein template catalyst based on the bacteriophage M13” [29].

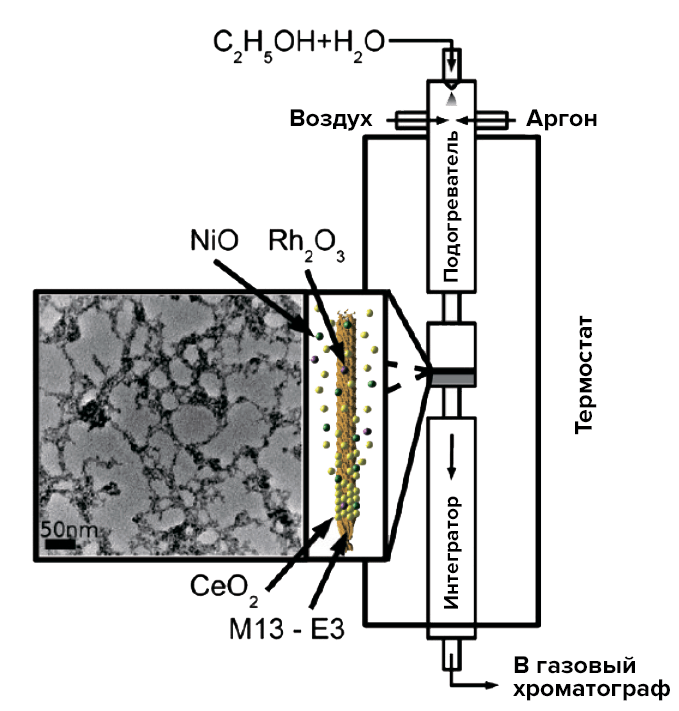

Picture 31. Schematic diagram of the activity analysis of the obtained catalysts. It is worth explaining that the integrator performs an analytical (identification) role here. The photo on the left shows the nanostructure of the surface of the viral catalyst. From the same article by Angela Belcher [29].

As a result of genetic engineering manipulations with the main protein of the pVIII virus, scientists obtained the so-called glutamate-saturated phage (E1) (with three additional glutamic acid residues). Its surface is strongly negatively charged at a neutral pH, which makes possible the deposition of metal ions and the formation of the aforementioned nanowires.

A similar catalyst is created by introducing a hybrid virus into a solution with chlorides of nickel, cerium and rhodium. After treatment of metal salts with hydrogen peroxide and sodium hydroxide (in the right concentrations to prevent the destruction of the bacteriophage), the corresponding oxygen compounds were formed. The catalyst is cleaned of viral particles by heating to 400 °C. The porosity of the biotemplate catalyst (and hence the activity) is really amazing — with a pore diameter of less than 4.5 nm, there are quite a lot of them. The use of viruses makes it possible to increase the active surface of the catalyst, which, combined with the pore distribution, gives a high selectivity of the new catalyst.

After synthesis, the catalyst was tested: for this purpose, a mixture of ethanol and water was passed through it in a special installation, and the substances at the outlet entered a gas chromatograph for identification. The desired result has been achieved — the conversion is catalyzed and hydrogen is released. A 10% Ni@CeO2 rhodium-free catalyst was also tested. In this case, almost 100% ethanol reformation was achieved at a relatively low temperature of 400 °C.

Thus, we have another example of a technology obtained using biotemplate synthesis on a virus matrix — a catalyst for hydrogen energy (even in a certain sense of bioenergy), the essential advantages of which are improved long-term stability, low sensitivity to surface decontamination, and small pores of approximately equal size.

Picture 31. Schematic diagram of the activity analysis of the obtained catalysts. It is worth explaining that the integrator performs an analytical (identification) role here. The photo on the left shows the nanostructure of the surface of the viral catalyst. From the same article by Angela Belcher [29].

As a result of genetic engineering manipulations with the main protein of the pVIII virus, scientists obtained the so-called glutamate-saturated phage (E1) (with three additional glutamic acid residues). Its surface is strongly negatively charged at a neutral pH, which makes possible the deposition of metal ions and the formation of the aforementioned nanowires.

A similar catalyst is created by introducing a hybrid virus into a solution with chlorides of nickel, cerium and rhodium. After treatment of metal salts with hydrogen peroxide and sodium hydroxide (in the right concentrations to prevent the destruction of the bacteriophage), the corresponding oxygen compounds were formed. The catalyst is cleaned of viral particles by heating to 400 °C. The porosity of the biotemplate catalyst (and hence the activity) is really amazing — with a pore diameter of less than 4.5 nm, there are quite a lot of them. The use of viruses makes it possible to increase the active surface of the catalyst, which, combined with the pore distribution, gives a high selectivity of the new catalyst.

After synthesis, the catalyst was tested: for this purpose, a mixture of ethanol and water was passed through it in a special installation, and the substances at the outlet entered a gas chromatograph for identification. The desired result has been achieved — the conversion is catalyzed and hydrogen is released. A 10% Ni@CeO2 rhodium-free catalyst was also tested. In this case, almost 100% ethanol reformation was achieved at a relatively low temperature of 400 °C.

Thus, we have another example of a technology obtained using biotemplate synthesis on a virus matrix — a catalyst for hydrogen energy (even in a certain sense of bioenergy), the essential advantages of which are improved long-term stability, low sensitivity to surface decontamination, and small pores of approximately equal size.

As a conclusion…

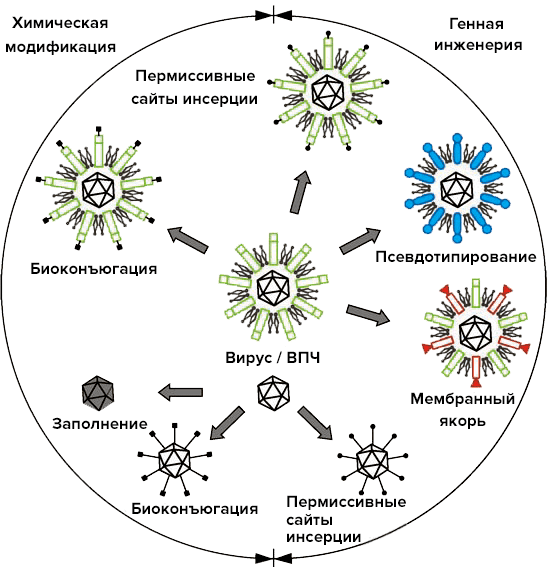

Anyone who engages in educational activities, and even more so in writing scientific articles, wants to tell you more about what they themselves are interested in. But as always, you need to know the measure. That is why, finally, I would like to say just a few words about the general approaches to the use of viruses and virus-like particles in modern technology (Pic. 32). Picture 32. The main modern types of possible modifications of viral surfaces for nanotechnology purposes. The diagram shows both viruses with an outer shell and non-enveloped viruses [30]. Image from the website Nanowerk.

Let’s turn to the diagram. Globally, all depicted manipulations with viruses are divided into chemical and genetic engineering. Interestingly, in both groups, similar results can be achieved using fundamentally different methods.

In materials science, viral particles are used as matrices for chemical synthesis. In this case, the required molecules are attached to the surface of the virus by so-called chemical bioconjugation. A nanoparticle is formed with the required number of molecules on the surface and the required distribution pattern. Similar “chemical” examples have already been mentioned: metallization/magnetization of viruses, assembly/disassembly when the environment changes, etc. Due to pH changes, HPV self-assembly can be regulated and used, for example, to encapsulate drugs.

There are many modern methods of viral bioengineering. This is especially true for viruses with an outer shell (a kind of quasi-plasma membrane). But, as always, there are those that the rest come down to [30]:

Picture 32. The main modern types of possible modifications of viral surfaces for nanotechnology purposes. The diagram shows both viruses with an outer shell and non-enveloped viruses [30]. Image from the website Nanowerk.

Let’s turn to the diagram. Globally, all depicted manipulations with viruses are divided into chemical and genetic engineering. Interestingly, in both groups, similar results can be achieved using fundamentally different methods.