We endlessly analyze and discuss various events and their possible causes, especially if something unpleasant or unexpected happens. It is known, for example, that family people often analyze the behavior of their “halves”, especially their negative actions. The coldness and hostility of one spouse more often than a gentle hug makes the other wonder “Why?”. The explanations they find themselves correlate with their satisfaction with their marriage in general. Dissatisfied with their family life, people usually offer explanations for negative actions that only make the situation worse (“She’s late because she doesn’t give a damn about me at all”). Those who are happily married, as a rule, explain what happened for external reasons (“She was late because there were traffic jams all around”). If the other half does some kind of good deed, the explanations also depend on the nature of the relationship: “He brought me flowers because he wants to sleep with me” or “He brought me flowers to prove his love.”

Antonia Abbey and her colleagues have collected a lot of evidence proving that men, more than women, tend to explain the friendly attitude of women with a certain sexual interest (Abbey et al., 1987; 1991). Such a misconception, expressed in the fact that ordinary friendliness is interpreted as a sexual appeal (it is called erroneous attribution), can contribute to behavior that women (and especially American women) perceive as sexual harassment or attempted rape (Johnson et al., 1991; Pryor et al., 1997; Saal et al., 1989). Such erroneous attribution is especially likely in situations where a man has a certain amount of power. The boss may well misinterpret the friendliness and agreeableness of the woman subordinate to him and, without doubting his correctness, will give all her actions a “sexual coloring” (Bargh & Raymond, 1995).

Such erroneous attributions help explain the increased sexual persistence of men around the world and the growing number of men from different cultures from Boston to Bombay who justify rapists and blame rape on the behavior of their victims (Kanekar & Nazareth, 1988; Muehlenhard, 1988; Shotland, 1989). According to women, men who commit sexual violence are criminals who deserve the most severe punishment (Schutte & Hosch, 1997). Erroneous attributions also help to understand why, at the same time, 23% of American women say that they were forced into sexual relations, while only 3% of men say that they had forced women to do so (Laumann et al., 1994). Sexually aggressive men are particularly prone to misinterpretation of women’s sociability (Malamuth & Brown, 1994). They just “can’t wrap their heads around it.”

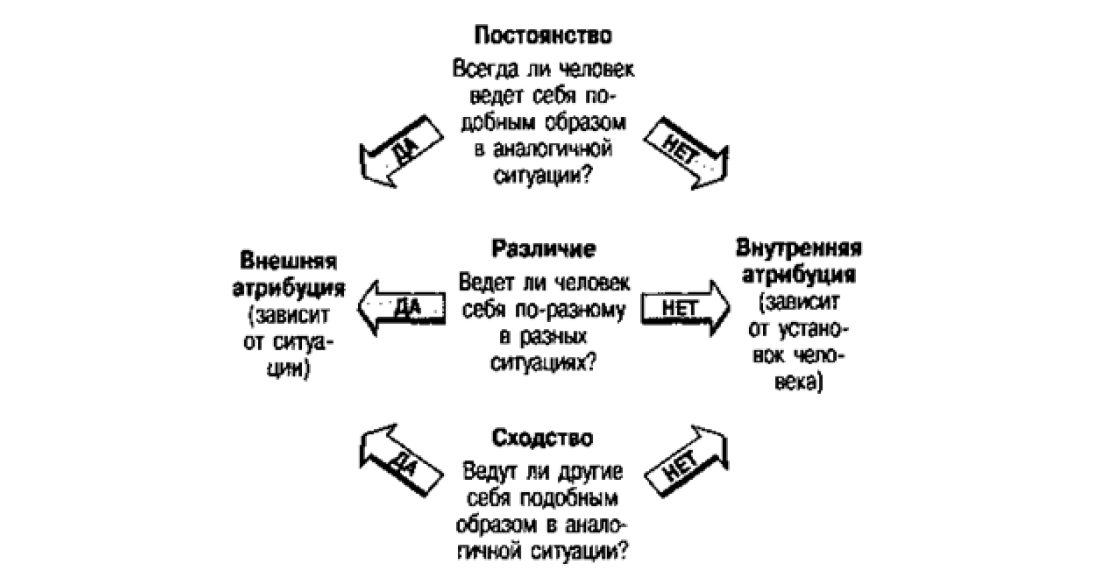

Attribution theory analyzes how we explain the behavior of others. Different versions of this theory share some common theoretical principles. Daniel Gilbert and Patrick Malone believe that “for each of us, human skin is a kind of special boundary separating one group of “causal forces” from another. On the sunlit surface layer of the skin (epidermis) there are external or situational forces, the action of which is directed inward at a person, and on the fleshy surface there are internal or personal forces facing outward. Sometimes the action of these forces coincides, sometimes they act in different directions, and their dynamic interaction manifests itself in the form of the behavior we observe” (Gilbert & Malone, 1995).

Fritz Haider, the widely recognized creator of attribution theory, analyzed the “psychology of common sense” that people use to explain everyday events (Hider, 1958). The conclusion he came to is as follows: people tend to attribute the behavior of others either to internal reasons (for example, personal predisposition), or to external ones (for example, the situation in which the person found himself). Thus, a teacher may doubt the true causes of his student’s poor academic performance, not knowing whether it is due to a lack of motivation and abilities (“dispositional attribution”) or a consequence of physical and social circumstances (“situational attribution”).

Don’t miss the most important science and health updates!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the most important news straight to your inbox